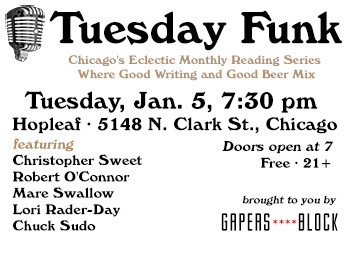

| « Saints be Praised -- It's Essay Fiesta! | The Open Door Series: March » |

Author Tue Mar 18 2014

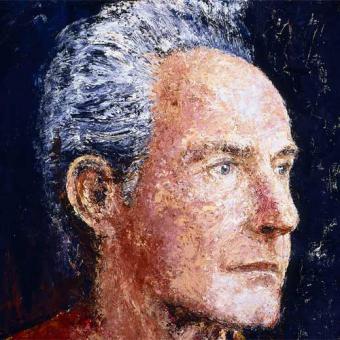

Story Week: Barry Gifford

I watched the man I thought was Barry Gifford talk to another, much quieter man, who really was Barry Gifford. The first Barry Gifford moved his hands eloquently and drew curtains in the air with his fingers. The real Barry Gifford said nothing and blinked politely.

A moment later, Barry looked me in the face.

I was a staff writer for Gaper's Block, I said. "A web publication," Joe Mino intoned with a smile.

"I'll only have a few minutes," Barry said, glancing with apology to Joe, then Kara, then me.

"That's alright," I said. "I won't need long."

His eyes are milk-white in places; not cataracts, I am sure. He gazes harder in spite of them; perhaps to spite them. As I shake his hand my wrist is limper, my voice more boyish, my smile less genuine than I'd like. I am struck by Barry Gifford. I struggle for words and thank him.

"Thank you, Mr. Gifford," I say, and age myself. I shuffle into the anonymous deck of the auditorium and hide with my iPhone set to record. I listen to Barry Gifford and I watch him, and this is what I see and hear:

He is, above all, a tall man; not amused, not interested in politeness (though he is polite). He is the kind of man who knows what khaki shirts are for (they're for handsome men who can wear them). He is a gentle public speaker, raised in hotel rooms in Chicago, Key West, Havana, "all over". Barry says the names of places with force, like they were new and becoming old. Like "Los An-gel-ees" sounded new in the 60's. He says "Havana" the way my grandfather, a Greek immigrant, would say "Afghanistan" while reading the headlines aloud to me. As if "Havana" meant something more than Havana.

He returned to Chicago for high school, middle school and then he was "gone". This resonates with me and I write it down. Barry Gifford was, at one point, gone. As a kid, he felt he knew every part of Chicago. He feels disoriented now. "Which is good," he says. That means discovery and newness.

I sat next to a couple who held hands like if they let go they would die. They listened to Barry, but I think they were never not-thinking about each other. I remembered my sister telling me about "folie au deux" where a couple will experience mutual isolation from the world.

Barry reads a short story called Gator Story, or maybe that's just how he'd describe it. Most of the story is the cutting up of a gator, and when I imagine Barry teaching me how to do this, I can't help but become a child. He has a face that belongs to many ideas of fatherhood, but I don't know whether he has children or not.

As he reads he is conscientious of eye contact. He touches every point in the room. Barry has been doing this a long time. "People do all sorts of crazy things," a character explains; he had been so quiet cutting up the gator for two hours because he had been thinking of his father-in-law, imagining he was still alive under him, aware of what was happening but too weak to struggle. Barry writes of scary, beautiful things. He began writing stories at 11 and they haven't changed much, he claims. His first break came while in London; a literary agent thought his music lyrics were poetry; Barry sincerely believes said agent was trying to sleep with his girlfriend.

Barry doesn't own a computer. He's never even owned a slide rule. "I'm sure some of you have seen one of those in a museum," he says. He describes something called "Computerhea", wherein authors write 1,000 page books that might have been much shorter, better books. He's never even considered an electric typewriter because he's never wanted to hear the hum. "The insistence of what that hum means," he says, and leaves it at that.

A friend of his, Al Young, had a computer he was always pushing on Barry. He was so excited about computers. One day, Al -- who lived in Palo Alto -- called Barry over for lunch. When Barry arrived Al was sitting at his computer, his head hung limp on his neck, staring at the keys. "I've just lost 160 pages..." he said. "Well," Barry said, "I just came down to have lunch with you, so let's eat."

Barry says that what every writer always yearns for is an ideal reader - even if it's only one. He remembers Fred Elms, the cinematographer for Wild At Heart, gripping his hand at Cannes during a crane shot at dusk with Richard Strauss cut behind it. It moves Barry to tears, thinking about it. He chokes up. "If there are any filmmakers in the room," he says, "you'll understand this is the kind of shot you wait around for."

He is a handsome man with a high voice; a surprisingly high voice. It reminds me of Lynch's, and the two men are friends. But when Barry does an impression of Lynch I realize how different the two voices really are.

This is most of the afternoon, really - Barry Gifford tells stories. It's what he does on the page and it's what he does in front of a congregation of film and creative writing students at Columbia College. There are a few professors who can be spotted by their insistent and earnest desire for symbols and archetypes, but Barry is very reluctant to discuss these. When asked whether Bobby Peru, Willem Defoe's character in Wild at Heart, is the devil, he says, "no."

"I don't have that same symbolic need to assign everybody a role," he says. "I mean, when I say that Robert Blake's character, Mystery Man, is the alter-id -- he is! Everyone thinks they know what alter-ego means...it's too easy. But have you ever seen an alter-id in a feature film, right in front of you, that you couldn't do anything about, that's the key to the whole movie?" He smiles. "No."

As for the demonic Bobby Peru, "he's a bad guy like any other." Barry explains, "I'm a realistic writer. That's how I see it. That's how people appear to me."

"One thing that Lynch and I always agreed on from the beginning," Barry said, "When you enter the theater, you enter a dream world. You enter the dream as a participant It's an organic process." He stares at us. "You surrender to the dream." He clears his throat and steadies his voice. "A long time ago I realized that dreams were as important to me as waking life."

In City of Ghosts, a screenplay he wrote that Matt Dillon directed, Barry describes the idea behind the title: "when the younger man finally tracks down this older man and says, 'when are we going back to New York?'

"The James Caan character says, 'we're not going back to New York...New York's lost to us, it's the City of Ghosts'."

It's an important line in the movie, because the viewer has assumed up to this point that the title is in reference to Phnom Phen and Pol Pot. And it's not - it's New York City. When Barry finally got to see the film, the line had been cut.

"I couldn't believe it," he says.

They're screening the movie in Cannes, and just before the movie starts a "phalanx of Southeast Asian women...come in and sit down in the theater."

At the Q&A, one of these women stands up. She addresses Barry and the filmmakers on stage: "We came to see this movie because we thought that what you might have done was disrespect the Cambodian people of the Khmer, but in fact we liked the movie very much. You really did treat people with respect and we want to congratulate you on that.

"I have one question, though," the woman continues. "What is the City of Ghosts?"

And as he ends this last story he laughs, and doesn't stop laughing for a half a minute. The couple next to me whispers to each other. Doubtless they hadn't heard the story. It was about a writer losing something to the cutting room; losing agency; losing meaning, maybe; but Barry was laughing. I'd had him all wrong, from the beginning. His dark milk eyes wrinkle into a fantastic grin and his whole face contorts. We all watch him, from an auditorium away.

Not quite intimate company, but his laughter is not overpolite or obligated. He has sliced open an alligator in front of us after all; taught us something; and at the very least we were the brave children who stood by and watched.