| « The (Clean) Power of the People Don't Stop | Chicago Works on Your iPhone » |

Crime Mon Feb 14 2011

Study Chicago's Blue-Light Cameras? Why Bother

This article was submitted by freelance journalist Shane Shifflett.

After seven years and thousands of cameras, neither Chicago's police nor its public officials can claim that their video surveillance program, Police Observational Devices (PODs), is effective at stopping and preventing crimes. This shouldn't be a surprise, though. After sifting through mountains of crime data provided by the police and observing two Chicago neighborhoods, the Urban Institute, a public policy think tank in Washington D.C., couldn't say how well the cameras were working. What may be surprising, however, is that the police department looked into this twice before; they never shared the findings and evidence suggests no one will ever know if the system is truly effective.

In 2005, a group of Northwestern University students led by Dr. Mark Iris, professor of law and politics and former head of the semi-independent Chicago Police Board, examined 137 cameras throughout the city to conclude the system has "mixed levels of effectiveness." Which is more or less what the Urban Institute has said. Just one year later, in 2006, the Chicago Police Department evaluated 111 of its own cameras to uncover a measurable 13.7 percent decrease in reported crime incidents near cameras. Iris' study contained 100 pages of detail and analysis (with 42 pages of crime data provided by the police) while the police department's examination consisted of eight pages of findings and an additional 18 pages of crime data. But both of these studies have remained under the lock and key of the police department since they were conceived.

The problem is that after three attempts at evaluating Chicago's dystopian camera network, it appears the system was constructed in a manner that can't be properly studied. While the police plan to expand the system, Chicago's citizens can't be sure the existing cameras are working. Rajiv Shah, an adjunct professor at the University of Illinois Chicago who specializes in researching surveillance technologies, draws analogy with the pharmaceuticals industry, which has to know if the tools it deploys, the drugs, are making a difference.

"If we studied [pharmaceutical] drugs the same way, we would never know if they worked," Shah said.

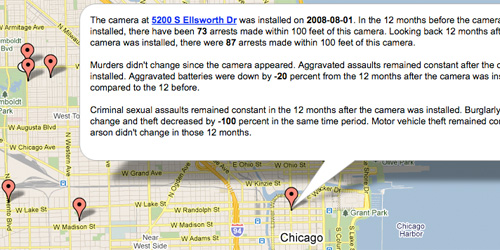

We've mapped the change in crime near 113 Police Observational Devices (PODs). Click on the map to explore our findings.

We've mapped the change in crime near 113 Police Observational Devices (PODs). Click on the map to explore our findings.

The study conducted by the Urban Institute marks the first time the police have bestowed upon the public some idea of how well the system works and cast the cameras in anything less than a positive light (to be sure, any concerns that the system was a bad purchase should be mollified because they found the cameras were, at the very least and in an abstract sense, cost effective). Despite at least $48 million hard tax dollars poured into this system, according to a spokeswoman from the Illinois Emergency Management Agency, the public has been given surprisingly few details and no benchmarks for success concerning these cameras.

"It seems to me that the people who want to bring these systems to every corner ought to be excited and thrilled at the opportunity to share information about how wonderful these systems are," said Ed Yohnka, the communications director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois. "...And that doesn't seem to happen."

If it weren't for Yohnka and the ACLU of Illinois, these studies, one of which sets forth a never-used rubric for deploying cameras so future research could yield firm results, may have never been seen. Three years ago, Shah submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to the police department requesting any research they had conducted concerning the cameras. Naturally, Shah's request was denied by the police. But he contacted the the ACLU of Illinois and they, with the help of two private attorneys volunteering their time, grappled with the police for years before the documents were turned over.

"The ACLU was the only reason I received these studies, they fought the city to make the studies public," Shah said. The ACLU-IL recently released a report taking issue with Chicago's use and deployment of surveillance cameras, including PODs, and calling for a moratorium on their installation.

Shah and Jeremy Braithwaite, a doctoral student at the University of California at Irvine, reviewed and reanalyzed the data contained in both studies. The police department's evaluation appears paltry and more optimistic than Iris' findings. It controlled for seasonal changes in crime (crime tends to increase with rising temperatures and during evening hours) and it examined outdoor and indoor crime separately, but it didn't look at issues concerning demographics nor the cameras' technical limitations. It looked at changes in crime over time within 330 feet of the cameras and noticed that more than half of the camera locations experienced a decrease in crime after cameras were installed. Their findings exclude narcotic arrests, and they state an inability to control for many variables that influence crime near cameras.

Despite several attempts, the police have not responded to requests for an interview to discuss the findings in their evaluation, Iris' study, and the Urban Institute's study.

Iris' study looked at the changes in crime at four different points in time: a week before a camera is installed, a week after installation, a week before removal, and a week after removal. His team also broke the cameras into the categories of effective, somewhat effective and not effective, and tried to associate demographic data with their findings. They even looked at changes in crime at varying distances from the cameras' lenses, starting with all crimes within 50 meters of a camera and extending out to within 500 meters. After all that work, they realized there was a great deal of variance in the effectiveness of cameras. Iris's team couldn't draw any grand conclusions about the how well the cameras deter crime because there was no statistical conformity among the different locations observed. In the end, he could only recommend future approaches for deploying cameras in a manner that facilitated the scientific method when studied.

Iris declined to comment on his findings for this story.

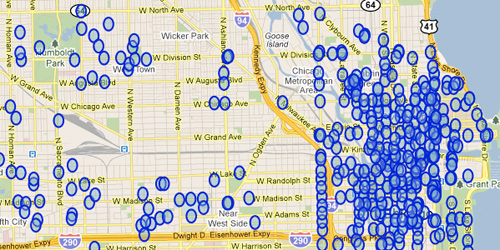

Chicago is one of the most surveilled cities in the nation. But what does that look like? See for yourself. We've plotted all the cameras the police department would turn over and surrounded those locations with a sphere to indicate the area these tiny orbs keep watch over.

Shah and Braithwaite took another stab at parsing the data in both studies to see if they could come up with anything. After accounting for a few mathematical errors in Iris' study (theoretically a reason why the police never released the study), Shah said, "Diffusing a large number of cameras throughout a city does not appear to be effective in reducing crime." His number crunching showed that cameras work best in high crime areas.

Shah said that much of the credit given to the cameras is being confused with a larger effect: amplified police attention on a problem. As crimes increase in geographic regions, the police devote additional resources to abate crime. Whether it's additional staffing to monitor cameras (a shared resource among at least 1,216 cameras accessible for real-time viewing, according to documents returned by a Freedom of Information Act request I submitted in April), or more cops on the streets, crime is generally reduced so long as police response to a crime remains timely. In other words, people adjust their behavior under the camera's glare only if an understood consequence, like an arrest, manifests soon after a crime occurs.

But because the cameras are so pervasive and were installed without establishing control groups -- regions with similar demographics and crime patterns but lacking only in cameras -- the effects of the cameras can't be definitively ascertained, Shah said.

Criminal theory and anecdotal evidence suggests that cameras in areas with low to moderate amounts of crime don't realize the same benefits because the people under their watch recognize the likelihood of being arrested for committing a crime in their presence is low.

Some residents have witnessed criminals' indifference to the cameras. "Something is either wrong with the cameras or they mislead the public by saying they would do this or do that," said Brian Lewis, a resident of the Woodlawn neighborhood on the South Side. According to an analysis of police documents, Woodlawn has at least nine cameras and a moderate crime rate, and Lewis says he has seen drug dealers slinging dope within the cameras' range. "It's real obvious that they aren't doing what they supposed to be doing, unless they was trying to instill fear by saying we got a camera right here to see what you all are doing."

But Shah's analysis could only go so far. Because the cameras have been deployed in such an erratic manner as the police respond to various stimuli, there are no areas left without cameras to compare against areas that have them. It's the same issue that has hampered the Urban Institute's effort to account for the performance of Chicago's camera system. Iris and his team enumerated a few options for the police to follow if they wanted to ensure quality results and avoid this issue in future studies. Both the police evaluation and the Urban Institute have looked at the cameras since Iris' team completed their study, and it appears his recommendations weren't heard. Dr. Nancy La Vigne, the director of the Criminal Justice Policy Center at the Urban Institute, who is in charge of researching Chicago's cameras, said the previous studies weren't provided to her team and that the police department had not followed any of Iris' recommendations.

Still, police continue to feed ambiguous statistics to the press and stand behind their terribly expensive system. In an August 2010 interview on WBEZ's Eight Forty-Eight, Chicago Police Commander Jonathan Lewin said nearly 5,000 crimes have been solved thanks to the help of the cameras since 2006. There were 734,643 index crimes since 2006, which include murder, rape and burglary, according to police documents. Using Lewin's figures then, at most 0.68 percent of crimes from 2006 through July of 2010 were solved with the help of cameras.

Lewin didn't indicate whether those 5,000 crimes are only index crimes or if that number also included quality-of-life crimes, such as narcotics arrests. Including such arrests would also greatly reduce the percentage of crimes solved using cameras. In the same conversation on WBEZ, La Vigne and Lewin deflected calls for increased transparency by reminding listeners the system is cost effective based on estimates of costs to society given various crimes.

David Coleman, a managing partner at the Avrio RMS Group, one of the contractors that supply surveillance equipment to Chicago, noted that crime statistics are only one way of quantifying the cameras' effects. Because the cameras can be used by several different agencies for different purposes, like allowing emergency dispatchers to look for dangerous elements of a major accident before responders arrive, there can be many different criteria for success other than reductions in crime.

While Shah and La Vigne can both agree with Coleman, the evidence, or lack thereof, indicates the police aren't utilizing their system efficiently.

"Chicago should stop trying to have a blanket of cameras throughout the city, and instead focus on high crime areas and give up the idea of a camera on every corner," Shah said. "That's just a wasteful use of money."

~*~

This feature is supported in part by a Community News Matters grant from The Chicago Community Trust and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. More information here.

Shorty / February 25, 2011 12:25 AM

As a relatively committed CAPS attendee, I have learned that many of the cameras are not manned 24 hours a day and will only capture activity if the camera is targeted in a certain direction.

What probably started out as a good ideas has turned into a waste of valuable tax dollars.