I once proudly announced to a friend that I had quit smoking, a habit which we'd both shared for some years. My friend shrugged his shoulders as he lit up his next Marlboro. "Good," he said. "You weren't ever really a smoker, anyway. Now me, I'm a smoker." I gathered from his dismissive response that he meant that my time and experience as a smoker were below a certain par. For some odd reason, I felt a little insulted at this and I felt compelled to insist I really was a smoker, not some lightweight puffer.

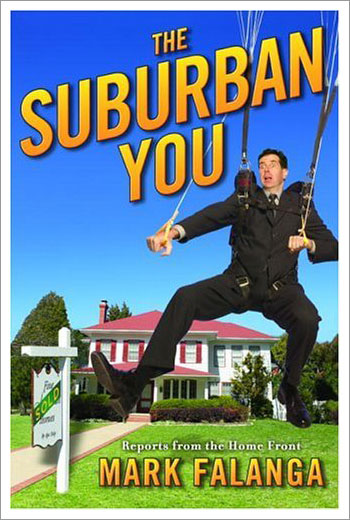

Mark Falanga's The Suburban You: Reports from the Home Front (Broadway Books, 2004), offers a humorous picture of a supposed urban dweller's transplantation to the suburban lifestyle. Aside from the fact that most of the rest of the world would see little difference between his adoped urban and suburban neighborhoods, Falanga seems to want us to believe he is a longtime city dweller suddenly transplanted into a bizarre new foreign world. But he himself offers us enough evidence to establish that this is hardly the case. Falanga was never truly an urban dweller, any more than I was ever much of a smoker. Which is to say, we both did it, but did we ever really live it?

Both Falanga and his wife were raised in upper-class suburbs. Falanga himself grew up in an affluent area of Long Island, the son of a successful Wall Street banker. On graduating from a small-town college in the early 1980s, Falanga joined the wave of new urbanites thronging to Chicago and other major American cities. He soon took over the real estate management of Chicago's enormous Merchandise Mart and began drawing a comfortable income. Falanga and his wife Diane lived in tony Lincoln Park for several years, until the arrival of children necessitated a move to the even tonier North Shore -- specifically to the village of Wilmette, such an exclusive place that I as a lifetime resident of Chicago have had the privilege of visiting it only four or five times. And I count myself relatively privileged, having grown up, as it happens, in Lincoln Park.

The book features short chapters containing embellished anecdotes. The style is unique for a book, something I would call a "situational second person," normally reserved for setting a scene in a short narrative: "You have spent three or four nights a week... looking for a house in the suburbs." The intent is to create a kind of detached, droll regard for events, so that we join Falanga in a kind of wry sociological visit into the new life, punctuated by his deadpan punchlines. I believe it is also to distract us from the painful fact that this is really an autobiography more than anything else. At some point in almost every paragraph the style effortlessly submarines into a different kind of "you," an oddly autobiographical one. In the hilarious passage where he described his wife's waffling on her decision to buy the new home, the narrative has changed to autobiographical: "You go to the basement of your home and craft a stick with a nail on the end of it to poke your contract and direct it out of the mail slot."

This is a sleight of hand. The style began to grate on me very quickly; normally used briefly to set a scene, here we have it for 200 pages. After many chapters which are far more exaggerated autobiography than descriptions of any other person's typical experience, I was left with the feeling that Falanga was attempting to pass off an autobiographical memoir as a humorous sociological package from the genre of Paul Fussell's Class. He forces us, then, to ask the question: Is this an important work? Is it a work of sociology, of humor, or of autobiography, or of some combination? What was Falanga's motive?

Like the book's promoters suggest, one might compare the style to Dave Barry or David Sedaris. However, it attains those authors' level of rapier wit less often. It does have many very winning moments, such as when Falanga meets his son's exotic, buxom Spanish teacher at the beach. The passage tells us so many things, but most of all it tells us that Falanga has mastered deadpan. He once expressed shock that his son could not remember the teacher's name. "'How can you not know your teacher's name after spending an entire year with her?' you ask disappointedly, a question to which you will get no response that you can understand." But when Falanga finally meets this beautiful woman, in her string bikini no less, he spends so much time trying to impress her that by the end of the encounter, when his son asks him what she told him her name was, Falanga mechanically tells him he has no idea.

Falanga also does a good job of reprising comedic devices at appropriate intervals. "You [have or do not have] sex that night" is peppered here and there as his reward or lack of reward for being a good or bad husband. If his "second first person" is tiresome, we are charmed by his skill as a storyteller.

(Shifting person or tense is a device sometimes used by a writer to sidestep some difficulty. I wrote above that "we are charmed by his skill as a storyteller," but who are we? I mean I am charmed, don't I? Or, better yet, I was charmed. I changed the person to invite the world to agree with me even though you probably have never read the book. I used the present tense to augment the timeless sanctity of this abstract "we." What kind of a scam am I running here?)

Whatever devices he uses, I believe what Falanga really wants to do is to tell us his own story. He does this very well in so many ways. He is, true to his Italian roots, a raccontatore of family anecdotes. When his wife wants to buy some new chairs for their home office, she is oblivious to the fact that her husband, in his position, is extremely well connected with the world's top furniture designers and could easily obtain a free roomful of classy European office furniture with a single phone call. She would prefer to take the advice of her friend Jane and go to a store. When at length he finally convinces her and uses his clout to score two gorgeous and very expensive chairs direct from the designer, she complains that the room now has too many chairs. Here and elsewhere, Falanga is also a Munchausen, allowing his self-portrayal as the occasional quixotic buffoon to elevate him in the larger story. It is another storytelling motif, striking that delicate balance between self-aggrandizement and self-deprecation.

Does this make it an important book? If this book has some anthropological value, it is because it is a self-contained artifact of this very interesting phenomenon of mutual aid, of the duality in the human need to relate anecdote: in having others hear your story, you are helping yourself.

Falanga does this again when it is his turn to host a block party. In this highly competitive community, Halloween parties are catered, house bragging rights prove size does matter, and the best block parties are fondly remembered for months. Falanga's ace card is that his neighbor is Matt Walker of the Smashing Pumpkins, who has agreed to perform. Falanga misses the whole performance (and the joy of drinking in his neighbors' envy) because Diane wants him to put the kids to bed. So, he loses this round. But in a subsequent chapter, when they host a dinner party, they are faced with a sexually explicit comment from a wildcard guest, the Guest from Hell, which leaves the entire company dumbstruck. To save the dinner, Falanga reprises the block-party victory: "What are you all doing for your block parties this summer?" Here he demonstrates excellent flair with his formula: in a few paragraphs, he tells one of his personal stories, gives us a snapshot of upper-class life, and hits us with a well-placed punchline.

Although the book has many qualities, the overall effect is not dazzling. After a point, the prospect of finishing the book hinged on whether I was willing to shift perspective and read the stories in context with Thorstein Veblen, Vance Packard and Paul Fussell, as perhaps the next generation of sociological autoanalysis. It is 105 years since Veblen's seminal work, where we are introduced to the notions of invidious distinctions and conspicuous consumption. It is a half-century since Packard, two decades since Fussell. This case study of Falanga's can tell us something, and it does.

The book documents some very interesting cultural artifacts. Falanga admits to embellishing, but if upper-class suburban life is anything near what he has describes, there is a lot to learn from The Suburban You. The competition among neighbors is obsessive. There is a general dissatisfaction and the compulsion to always reinvent, at least within the homeowner's property line. Although the suburb's motto is "Unity Through Diversity," the fear of life outside the suburb is palpable, such as when a brown person is encountered, or when the family wins a trip to a two-bit auto-wrecking facility on the South Side. After getting over their initial fears, after meeting "Latonya," the obviously black proprietor of the facility, they actually relax and enjoy themselves. It is sociological commentary.

As autobiography, the book does an admirable job of telling us a lot about Mark Falanga and his family life. I personally enjoyed reading it because, I have to acknowledge, I knew Falanga's wife Diane and her friends very well when they were in college. But I cannot imagine many others being too interested in their personal lives. Autobiography is for people who matter to other people. Although Falanga and his wife are interesting people, and could well become famous in time, it seems a little early for them to be indulging in widely published autobiography.

Diane and her college roommates were beautiful and gut-wrenchingly funny. Diane, though we loved her, was always enormously self-centered and this apparently has translated into a very funny combination as Falanga portrays it: Diane as domineering, demanding suburban mom and Falanga as her well-whipped straight man. This is more a story about Diane than Falanga, as it seems their entire life clearly is driven almost exclusively by Diane's priorities.

As a synergy of humor and sociology, along the lines of Fussell, the autobiography is almost tolerable. Clearly, this was the motivation for the book. But of course it cannot be considered an important work in that regard. It also suffers from the fault that it is not objective.

So, how is this book important? Throughout it, Falanga seems to be telling us that his wife Diane is a bitch. Now, knowing Diane -- and notwithstanding the fact that she is a stunningly attractive and hilarious woman whose combination of beauty and outgoing personality could hold its own alongside Bette Midler or Barbra Streisand -- I would not be very surprised if she were the bitchy, insensitive wife that Falanga portrays her as. This begins to scream at us by the middle of the book. Halfway through, he is more direct about her control: "She knows that she can effectively manipulate your thinking to align with hers..." Furthermore, he seems terribly unhappy with his adopted life, as if he is missing something somewhere. He lusts after several women. The grass is always greener. He has an inferiority complex. What's troubling is that, although this is parodic, it also is not parody -- these thoughts must actually be going through Mark Falanga's mind at all times. He does not appear to be a happy man.

By the end of the book, I recognized that this is an important work after all. Namely, it is extremely important for Falanga. This is Falanga's psychological cathartic testament, one in which he opens up to the world and exposes his traumas. The world becomes his armchair psychologist. With him and for him, we can laugh at his situation and encourage him that Diane's redeeming qualities must certainly make life with her worthwhile.

The autobiographical content is almost excusable because it is almost consistently funny enough. But it is a sad comment on such a well-promoted publishing effort that the book could stand to be about 25 precent funnier and 25 percent less autobiographical. His friend who "has written a bunch of big-time Hollywood movies" was the first to discover and promote his average writing talent. It does not surprise me that a work that is only so good can be picked up by a publisher, since Falanga obviously has class connections appropriate to his status, and it didn't hurt that he could afford to retain a major literary agent. HBO already has bought the TV rights for this book. Indeed, many so-so books work brilliantly on screen. But in the end, the book is only so-so.

In contrast, I once helped a woman who was self-publishing a fiction set in the same South Side of Chicago that Falanga has avoided all his life. The woman has never been inside a Wilmette home. She wrote a poignant work about maintaining relationships amid poverty, and her style was brilliant, understated, unique, engaging. I could feel the old ghetto streets move under her prodigious pen. The book was a pleasure to read. As a work of art, I have to say it exceeded Falanga's in practically every way. Yet this woman had to struggle even to self-publish her work, and although she worked so hard that she learned more about the book industry than I ever knew, though she hawked the books on her own at local bookstores, she could not afford to market it herself.

It's unfortunate that the publishing world is often driven more by connections than true talent. This, the story behind the story, is the most compelling sociological statement behind this book: that an upper-class white man with middle-class talent will see success long before a working-class black woman with upper-class talent. And that's not very funny.

In the end, the deadpan humor is a welcome change from all of the over-the-top work we see. But I feel Falanga's first book could have been better. I have the impression that he wrote the book to show up his neighbors. Because of this, he had to change voice. But the voice was all wrong. The epilogue, which (still in his "you" style) tells all about his charmed rise to fame, should have been put in the beginning of the book. It should not have been called The Suburban You, it should have been called The Suburban Me. Falanga should have put his ambitions aside, admitted that, as a suburbanite at heart, his perspective on city life is inadequate to make contrasting comment. Although he still squeaked by with a decent book, he should have taken the time to write something because he loves to write, rather than to gain admiration. Let his second book come from there.

Now, where did I put my damn cigarettes?