When he enters the bar, couples in blue jeans stop their two-step. A crowd parts, and a patron calls out, "Hey, it's the Tamale Guy!"

I was tucked into a red vinyl booth at the California Clipper, just north of Augusta on California Avenue. A band I liked had on their best embroidered Western shirts and was playing country music — twangy steel guitar and bouncing upright bass.

I stood up in my seat to get a better look at the scene — and there he was. A stout Latino man with a mustache and red travel cooler peddling tamales between the tables.

I was having a lucky night, I thought. This was the second time I'd seen him. The first was hours earlier, a mile away at the Rainbo Club on Damen Avenue.

"Are you sure," a friend asked later, "that it was the same guy?"

That's when it hit me. Until that moment, the Tamale Guy was just the Tamale Guy, a man with hot food, a vaguely familiar face, and a name I never thought to ask. He roamed from bar to bar, through Ukrainian Village, Wicker Park, Bucktown and beyond, feeding the young, the hungry, the drunk. Could there be more than one? I set out in search of the answer.

"Tamales! Tamales!" A quiet, persistent cry cuts through the din at the Rainbo Club early the next Saturday night. Behind the beer taps, a stage with ornate, white, polished-wood columns and a black velvet curtain suggest the bar's former glory as a strip club — and favorite haunt of Nelson Algren. Across the dingy, checked linoleum floor, a young man in tight jeans, thick black glasses and a full beard scans the newspaper in impossibly dim light. A vintage punk record crackles over the sound system.

The Tamale Guy jaunts through the bar quickly, his head darting from side to side as he eyes every duct-taped booth and barstool in search of takers.

"Uno de queso," I request as he approaches me near the pinball machine. His mustache is thin and sparse, his hair matted but curly, his eyes dark brown. He's dressed in relaxed jeans, white sneakers and a parka. He draws a packet of cheese tamales from amid the parcels of pork and chicken in his cooler and stuffs a generous stack of napkins and salsa cups into a plastic shopping bag. I tell the Tamale Guy that I'd like to interview him sometime. His name, he says, is Claudio Lopez Velez. At Claudio's request, I do my best to speak in Spanish, but I'm rusty. Claudio ties the bag in a knot, and I hand him $5. He has to keep moving, he tells me, and work his way down Division Street as crowds peak. He's too busy to talk now, he says. He does not have a phone. "Miercoles, Miercoles." Wednesday, Wednesday. OK. "Gracias," I say. "Hasta luego."

I dig into the Ziploc bag marked queso and begin to peel and unroll the moist husk — the color of the wrapper fades from deep orange to buttery yellow, like a sunset. I can almost feel the steam hit my face as the husk falls away, and I bite into the rich, flavorful hunk of cornmeal, threaded with strips of green pepper, lodged with pockets of salty cheese.

Tamale preparation typically involves spreading textured corn dough called masa onto cornhusks that have been softened in water. Tamales can be filled with just about anything — in Mexico, you can find squash, fish or even pumpkin-seed tamales. Once filling is added, the husks are rolled and folded up, and the tamales are steamed in a double boiler for several hours. The original Nahuatl word, tamalli, means "steamed cornmeal."

There's a great deal of history packed into each little cornhusk. Warriors often carried tamales with them during battle because they were easy to pack and eat, an ancient form of fast food. Early methods of cooking involved crisping the tamales in hot ash. In later practices, they were steamed in underground pits. Indigenous people of Mexico frequently offered them to gods — and in the 1500s, to new visitors from Spain.

Do Tamale Guys know all that history? I'm not sure. But Tamale Guys are aware of one great, universal truth: Drunk people want food.

Later that night, in the dark back room of the Hideout, three sweaty, bearded guys play hard rock in the fog of a smoke machine. It is hard to see a face, or hear a word, but suddenly I can smell him. Steaming cornmeal and cheese.

Through the murk, I glimpse the exposed back and bare shoulders of a woman in a strappy dress. She would have looked more appropriate at a wedding, except that her elbows are up on a high table, her head down, her jaws working hard. She and her companion peel back damp cornhusks, dunking dense cornmeal logs into tiny cups of salsa.

I burst through the swinging door, into the main bar. Until that moment, I was just another drinker, another young woman with a slightly red face and a purse full of beer money. But when I lock eyes with Claudio, he chuckles and agrees to chat — I can't believe he remembers me, but I'm delighted he does. I find out he's from the state of Guerrero in southwest Mexico but has been in the United States for more than 10 years. He lives in Pilsen with his wife Maria. She cooks the tamales. He sells them via car. It's 12:20am, an early night for some, but Claudio tells me that this is his last bar. He has to be on his way.

"Miercoles?" I ask before we part. Miercoles he says, before he disappears into the crowd.

That Wednesday, I pull up a barstool at the Rainbo and begin my stakeout. Andy Mikonis, a tall, sturdy man with a well-kept beard and unruly, blown-back brown hair, pours pints for me and my friend Jen. Mikonis, dressed in a blue work-shirt, has tended bar at the Rainbo since 1994 — long enough to have witnessed the Tamale Wars.

"Red cooler versus blue cooler," Mikonis recalls. He says Claudio was "kind of a jerk at first," and remembers watching Claudio push out Chicago's preeminent Tamale Guy several years ago with aggressive territorialism. (The former Tamale' Guy's whereabouts are now unknown, although at least one bartender attests he occasionally comes to the Rainbo and holds a bag of tamales above his head in silence.)

"Once he came on the scene, he never left," Mikonis says of Claudio. "He was the one who really started this thing."

Today, Claudio still contends with at least one other Tamale Guy. He also is a relative newcomer to the scene, who sports a slightly thicker mustache and navy baseball cap. It was this man, who first introduced himself to me as Pedro, whom I spotted first that night. I would learn later that his name is actually Julio, and that the phone number he gave me didn't work.

Jen asks for a packet of queso tamales — like Claudio's, they're sold in packs of six. Julio says he doesn't have time to talk now. He is even more hurried than Claudio and has less tendency to smile. Once he's out the door, off to the nearby Inner Town Pub, Jen confirms that the queso is actually puerco.

Mikonis says the Tamale Guy — whether it's Claudio or Julio — can be "a slight nuisance," mostly because of the physical aftermath of eating tamales. As a bartender, Mikonis frequently has to pick spent husks out of the recycling bin and wipe salsa off the bar.

Not long after Jen and the bartender polish off Julio's pork tamales, I spot Claudio. I purchase a packet of queso tamales, and Claudio and I talk briefly in Spanish. He has a few more moments to spare since it's a Wednesday.

I go over some of the details from last time, and I learn that Claudio is 40 years old. I ask if he has children. Three, he says. They remain in Mexico. He answers the question politely but without emotion, as if I were taking a survey.

He says he began selling because he needed money. He used to work at a printing company on the Northwest Side, but now neither he nor his wife holds a day job.

Claudio sells at least three or four nights a week, from about 8 until after 1. Maria prepares 20 packets — 180 tamales — each night. Claudio fills the salsa cups. OK, he says. Is that enough? Tengo que irme. I regret that he has to get going, but I can't keep him from his work.

I had imagined myself riding shotgun with the Tamale Guy, shadowing him in each dark tavern, notebook in hand. Maybe I'd visit Maria's kitchen, I thought, or be asked to roll a few husks. I was too caught up in my fantasy to recognize the Tamale Guy's reservations about me. Unofficial food sales are illegal without a city permit. I might prod him about that, ask about his immigration status, or worse, slow him down.

I arrange our red and green salsas on the bar and open the lids. I unwrap the soft, ridged husk. The tamales are nice and hot — the perfect complement to crisp, cold beer. Claudio was the first vender to introduce cheese tamales, Mikonis says, making him a popular man among vegetarians like me.

"Nice texture," Jen says, munching on masa. "Subtly corn flavored. Lovely."

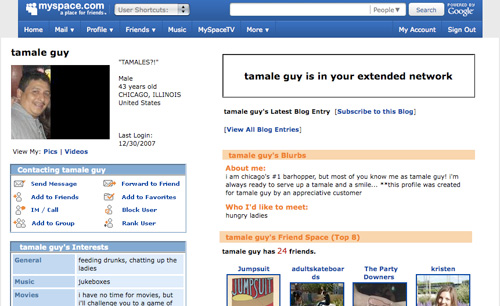

"Claudio's are better," Mikonis says after tasting the cheese tamale. The consensus is that Claudio's cornmeal is grainier than Julio's, and the tamales are not quite as dry. Claudio has a reputation for quality — one of the bartender's friends even had Claudio cater a private party. Last Halloween, I saw someone dress in costume as the Tamale Guy, pasting on a mustache and toting a Playmate cooler. Claudio also has two MySpace pages. On one, he is listed as "tamale guy" (age 43) and on the other, "Mr. Tamales" (age 47). There are two photos of the demure man, face shining, smiling nervously. A cartoonish loop of mariachi music blasts as soon as one page loads.

Beside us, a woman with wavy blonde hair leans back on her barstool and declares, "Claudio's tamales are better because they're made with love."

The next weekend, I round three bars determined to catch up with the Tamale Guy. Corner taps still abound in Ukrainian Village, so it's only a short walk from the cozy Inner Town, with its dangling stained glass lanterns and kitsch-coated walls, to the more austere Happy Village, where intense ping-pong rages in the back room and smokers clog a rainy beer garden. At Club Foot, my last stop of the night, knickknacks and rock memorabilia coexist with an old white tin ceiling and long wooden bar.

With his black hoodie, dark beard, and heavyset build, bouncer Rob Hanratty looks the part. Hanratty has a thin line drawing of a mustache tattooed onto his index finger. If he needs a disguise, he can simply hold his "fingerstache" beneath his nose.

Hanratty encounters his fair share of unofficial food vendors. The Pizza Guy is famous for arriving unannounced late at night, holding a hot, boxed pizza. "Hey, did someone order a pizza?" the Pizza Guy will ask. When nobody says yes, he offers the pizza for $10. Hanratty claims he's a disgruntled Domino's driver who was fired after a car accident.

The Muffin Lady, Shirley Peña, starting selling "special," pot-laced muffins at area bars in 1999. She was jailed for muffin sales in 2004 and later released, and today is no longer a presence on the unofficial bar food scene.

That night, Julio was the only food vendor I had seen. I wasn't hungry for tamales then, and perhaps since I wasn't buying, he wasn't interested in talking.

"Julio is the loud one," says Club Foot co-owner Chuck Uchida, as he fills and pours behind the bar. Uchida, a stout goateed man in a loose t-shirt and black-framed glasses, says that Julio's use of terms such as jefe or gringo prompted him to ask the Tamale Guy to tone down his language with patrons. (Julio called me mi amor when I saw him at the Inner Town. "Sorry my love," he said in Spanish, politely rebuffing a request to chat.)

As to the erstwhile Tamale Guy, the one who disappeared several years ago, Uchida heard he was "living well" in Mexico after his Chicago reign.

After one in the morning, I've emptied enough brown bottles of cheap beer that I'm starting to get to get hungry — but the Tamale Guy is nowhere to be found. Though it's spring, frozen rain pours on Chicago as my boyfriend and I step outside. We say goodbye to the bouncer, who's having a smoke outside, and begin our walk back to the Inner Town, where we've left our bicycles. I'm not looking forward to riding home in this mess, and I could really use something hot, portable, and delicious.

And just when I think it's over, I hear those words that tell me the Tamale Guy is near: "Hey man, you got pork?" asks a tall, gangly guy in skinny black pants and a sweatshirt, emerging from the Inner Town. Claudio's already opening his cooler as we run up.

"Can we have some cheese tamales?" my boyfriend asks Claudio. While he readies our bag, I ask him if he has time for a couple more questions.

Claudio smiles, sighs, and says he's already told me everything. I tell Claudio that I want to know more about how he came here, how his wife makes the tamales — more about his vida.

There were still so many unknowns. A writer online recorded a different last name and age for Claudio. Bar personnel have their own theories — Hanratty told me he believes Claudio lives near Club Foot, not on 21st Street, and that Claudio's sister, not his wife, makes the tamales. A Spanish language teacher in Logan Square heard that Claudio was once an "aquatic engineer" back in Mexico. If the Tamale Guy was secretive, if he didn't want me riding with him (there was no room for me with all those tamales, he had said), he had good reason. His trade was illegal, his legal status uncertain, his schedule tight.

"Mi vida?" Claudio says reluctantly, stretching his face out from his hoodie and looking up at the frozen rain.

He picks up his cooler and opens the door to an old, dark blue Toyota station wagon. We exchange goodbyes, and he tells us to be careful on our bicycles — especially in this weather.

"Es peligroso," he says. It's dangerous.

Watching him drive away down Thomas Street, a warm plastic bag crinkling in my hands, I had gotten my tamales for the night. But I still hadn't found the Tamale Guy.

The next time I saw him, back at the Rainbo, we hugged and exchanged kisses on both cheeks.

When I told him that I was almost done with my story about him, he lowered his head and rapidly made the sign of the cross. Even though I thought I had gotten closer to Claudio, what he prayed for at that moment in the darkness of the bar — that he sell enough tamales to make it back to Mexico, that no immigration official ever find him, that I shouldn't see him blush — I could never be sure.