I ride the Jeffrey twice a day, five days a week. I guess it is called the Jackson Park Express now, but I still call it the Jeffrey.

The only white folks who ride the Number 6 Jeffrey Express bus are affiliated with the University of Chicago, but in general most of these must take the Metra downtown, or maybe don't go downtown at all, because the ratio on the Jeffrey, black to white, is about seven to three.

Oftentimes I sit in the back of the bus, which is reserved for young black males who either sleep or listen to music. I have no particular preference as far as seats go. I sit at the back only because it is, by un-agreed-upon agreement, the province of someone I am not: I am neither black nor male.

Once, an older black lady with a few missing teeth and good quality clothes, if 15 years out-of-date, started talking to me. I was sitting near the front of the bus this time. The teeth were only missing from the back of her mouth; she seemed like the type who was rich enough to take care of teeth if they are missing from the front, but not rich enough to find replacements for the teeth that go missing from places where no one but strangers on the bus will see.

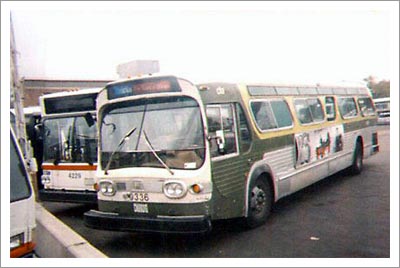

At this point, the bus line had already tried to change its name from the Jeffrey to the Jackson Park Express, and the busses, too, had changed, from the super long caterpillar-like ones with '70s-era orange-and-yellow-colored stripes down the sides, to the fancy ones that play music in the background at intervals. The music usually comes on when you're trying to get through the difficult passage in that book where Faulkner or somebody is talking about something complicated, like about how memory knows and remembers, and remembers longer than it knows, and has its own uncontrollable instinct where you don't realize you remember something until it has been transformed from memory to knowledge.

Something like that.

Fig1. The way CTA busses used to look.

The music then becomes a pre-recorded speech about not eating on the bus, and about how the CTA is trying to serve you better...but only if you aren't hungry, I guess. And you always end up rereading the Faulkner passage.

But I didn't reread the passage that day, because the old black lady with missing back teeth in high-quality former fashions starting talking to me. Somehow, eventually (around 47th Street), she got on the subject of TV evangelists. I battened down the hatches and prepared to pretend to listen because Lord knows how much my atheist ears hate hearing, but are strangely attracted to the sound of, Gospel-talk.

She talked about one televangelist in particular. She told me that he came to us from Selma, Alabama, which town I maybe incorrectly connected to the Civil Rights Movement.

She told me that the preacher once healed someone on TV while she was watching. I asked her if she believed in that stuff. We looked into each other's eyes for the first time; up to this point we had only been talking and glancing out at one another from the sides of our faces.

She said, �I don't know...but I want to.�

And I almost cried, because a stranger who was so unlike me had suddenly said something that was so like me.

~*~

A long while before that day, I was riding the Jeffrey to work. It wasn't quite rush hour. Just after it, in fact. A crazy lady was riding the bus, yelling about how she didn't want to go to wherever it was she was going. She was alone, so I'm not sure who was forcing her to go, but her helplessness was genuine.

My throat got tight because I didn't want her to go there either. It didn't seem right that she should have to go somewhere she had such a strong objection to going to, but no one probably listened to her objections because she was crazy. And besides, going to the place was probably for her own good.

My throat was tight also because I didn't want her to keep yelling.

This time I was trying to get through Faulkner or someone writing about how bad women can be fooled by badness but good women never can. Good women don't have to worry about who's good and who isn't and so can spend more time on the trail of sin. Bad women sometimes get fooled by badness because they have hope that somehow it isn't really badness, and might even be goodness.

Something like that.

I was shifting around, discomfited by the yelling, sitting by a young black man listening to music at the back of the bus. Suddenly it seemed to me that she ran up to me. The crazy lady. Ran. Or disappeared from one spot, standing in the middle of the bus, screaming, and reappeared in the spot right in front of me. She flicked my book, hit it with a knuckle. Not hard enough to make me drop the book, but hard enough to move it back toward my chest. Hard enough to scare me a little and surprise me a lot. I looked up at her, all eyes, and she calmed down suddenly. She said, in a regular voice, not crazy, "I don't want to go. They can't make me go." I said, gently, as of she wasn't crazy, "I know. I heard you."

Because of construction, the Jeffrey wasn't getting onto Lake Shore Drive at 47th, but was turning up and using side streets to access the freeway at some street in the 30s. 35th, maybe. The crazy lady rang the bell furiously and yelled that she needed off. The driver wasn't scheduled to let anyone off -- it was an Express, after all -- but bus drivers tend to make exceptions for the crazy and intoxicated.

I tried to recover from the scare, and instead of getting back to Faulkner or whoever, I imagined that she wasn't crazy at all. I imagined that she had wanted to get off of the bus at the exact spot she did; she had tricked the bus driver into invoking the loophole allowing for the unscheduled letting-off of the crazy and intoxicated. I imagined her strolling, in all sanity, from the curb right up the front walk of the house into which it was her plan to go all along.

In the dead of winter one week I caught a bug. Because the temperature was below zero, and because mostly poorer folks ride the Jeffrey and maybe don't know that they are allowed to complain, taught somewhere along the way to simply take their lumps, the busses were behind schedule. We stood outside in the cold for long periods, waiting for Jeffries.

But people are friendlier in times like these, so I tend to appreciate communal hardship.

At work I fired off, in my best prose, an e-complaint to the CTA regarding the bug, the temperature and the delays. I received an obsequious, apologetic reply and was asked to track the Jeffrey's movements for the next week or so. I stopped reading Faulkner or whoever and furiously wrote down bus numbers, dates, times and corners.

One night, late, I plunked down in one of the backmost seats next to a black man, in his later 30s. He noticed how, with dark concentration, I wrote down the bus number and time. A Jeffrey had passed us, we disbelieving, a few minutes before the one we were on had stopped. I couldn�t remember the number of the one that had passed us. The guy next to me knew what I was thinking, because he leaned over and said, "The one that passed us was number 6532."

He then told me that he also was keeping track of things for the CTA. I asked him the name of the person for whom he tracked, and he couldn't remember. When I tendered the name of the guy for whom I was tracking the Jeffrey's movements, he said, "Yeah, that's it. That's the guy."

We complained about the Jeffrey the whole way home...about the long waits at the end of which a train of Jeffries appear, all in a line, drivers huffy, customers huffier. We discussed logistics, what the CTA should do to get the busses to come regularly instead of in clumps.

At the end of the ride he finally introduced himself, but I can't remember his name. When I was getting off the bus, I looked behind me and he was watching me. I looked again in a little, and he was still watching.

~*~

Months later, I was trying to reconcile two passages of Faulkner. In one, Calvin B. was the last of two children, in the other, the first of four. There were two Calvins, though, so you might think that the discrepancy wasn't really a discrepancy, that in one passage Faulkner was talking about one Calvin, and in the second he was talking about the other. But the second Calvin was one of six children, so the two Calvins couldn't've been the same. Wait...No, it was Nathaniel B. who was one of six...Christ A�mighty...

Anyway, I looked up and my fellow bus tracker sat down in the back of the bus, near me. He didn�t remember me, though. A few stops later a girl got on.

This was the third time over the span of a year that I'd seen her get on the Jeffrey. She is pretty memorable, even for people who don't have good memories. She is beautiful, but not in the Lincoln-Park blonde-and-tan way. More like the will-probably-be-a-makeup-artist- one-day sort of way.

She wore a raspberry beret one time. No kidding.

You can tell that everything about her is intentional, a performance. I think she studies at Columbia College or the Art Institute. And even though she's beautiful, I don't like her too much. She's one of these people with a New York-but-never-been-there accent. You know? Not like the Mafioso New York accent, more like the Madonna type.

She also gets one after another cell phone call. Or one time she did. Well, she always gets or makes at least one call on the bus. Her phone's ring is something clinical, phone-sounding, instead of one of those rings that's also a song. That doesn't redeem her though. Nor does the fact that she sits at the back of the bus with the young black men and me.

My fellow tracker honed in on her right away. I suddenly realized that this was his thing. He hits on women and uses something unique that they're doing as an "in" to start a conversation. His gimmick is to use their gimmick. Pretty brilliant, actually.

~*~

A long time before that happened, or maybe a long time after, I was sitting in the back of the Jeffrey between two black men. Well, sort of -- one of them was next to me, and the other was nearest the window on the opposite side of the bus in our, the rearmost, row of seats. The one next to me was drinking, doing the covert brown-paper-bag thing. He wasn't drunk yet, but he smelled. Not like alcohol, though. He just smelled like something bad smelling.

I couldn't take it. There weren't any other seats, and if I was ever to get through Faulkner, I couldn't stand up -� the book is too big and heavy to hold in just one hand, and you need the other one to grip the bus in whatever way you can. Plus, if I got up it'd be overtly rude.

So, I pulled a corner of my coat up over my nose.

I know this was covertly rude, brown-paper-bag covert, so it wasn't a secret what I was doing, but my nose is as sharp as my memory -- I had no recourse.

As we neared my stop, I realized that the two guys, the stinky one and the one who sat by the opposite window, had realized what was up and were laughing at me. They were giving each other looks, and when I got up to go there was a short outburst of laughter.

As I crossed the street away from the bus I turned to flip them off, but they weren't looking at me. They weren't even thinking about me anymore.

It's a strange thing: I think and write about and remember and know that I remember those who people the Number 6 Jeffrey Express Bus...but none of them give me a second thought.