Eddie and the Cruisers 3: Working Man Blues

(MGM, 2004)  ½

½

It's hard to believe after 15 years, anyone was still clamoring for another Eddie and the Cruisers movie, but like it or not, here we are confronted with Eddie and the Cruisers 3: Working Man Blues. Michael Pare is gone, replaced as Eddie by 21 Jump Street's Richard Grieco, long past his prime, but hardly outclassed by the muddled, ill-conceived script and hamfisted direction of first-time feature director Mark Linn-Baker.

You're forgiven if you've forgotten all about Eddie Wilson and his band of ragtag rock'n'roll heroes, but for what it's worth, here's a refresher course. Back in 1964, chart-toppers Eddie and the Cruisers, America's hottest (though fictitious) rock band, broke up following the apparent suicide of the band's charismatic frontman Eddie Wilson, who drove off a bridge. His body was never found. Twenty years later, an investigative reporter begins to suspect that Eddie Wilson may still be alive. That was the first Eddie and the Cruisers and odds are, if you were alive and had cable during the latter part of the last century, you've seen it about a half dozen times. It was cockamamie rock fantasy, cobbled together to cash in on the "Elvis Lives!" mania of the early 1980s. Still, the first Eddie did have a certain na�ve charm, as well as a handful of minor hit singles by John Cafferty and the Beaver Brown Band. ("On the Dark Side," anyone?) As such, it carved out a small but loyal following during its television and video runs, making at least one follow-up almost inevitable.

The first sequel, Eddie and the Cruisers 2: Eddie Lives! went by largely unnoticed in 1989, a clumsy attempt to cash in on the first film's maybe-dead-maybe-alive rock star mythology by bringing Eddie out of hiding for a triumphant comeback -- in Montreal.

You didn't see that one? It hardly matters, as Eddie and the Cruisers 3: Working Man Blues starts off with a nearly endless recap of the first two films, made all the more laughable by clumsy reshoots replacing Pare with Grieco.

As the movie proper gets moving, we find Eddie and his new band high atop the rock charts on the heels of Eddie's dramatic reappearance. Already, though, there's tension afoot: guitarist Rico is quickly developing a nasty smack addiction and drummer Sticks is considering leaving the band to pursue a lucrative solo deal. (Why exactly the drummer, of all people, was offered his own solo record is never adequately explained. But given that Eddie is a '60s rocker who sounds like Bob Seger and is still young and vibrant 40 years after his initial heyday, perhaps intense scrutiny of the film's logic is something of a fool's errand.)

Before long, an industrial accident strikes down Eddie's nephew Butch and gets the aging rocker thinking hard about the hard luck lives of America's union men. As the band disintegrates around him, Eddie struggles to organize a Live Aid-style benefit to benefit America's pipefitters, rediscovering his own blue collar roots in the process. Will the benefit come together? Will Butch walk again? Can Eddie's new love interest (Dorito's commercial star Ali Landry) reconcile her love of hip hop with Eddie's old time rock'n'roll sensibilities?

Writer/director Linn-Baker (best known for his role as Larry Appleton on television's Perfect Strangers) tries unsuccessfully to weave together a handful of disparate story threads, perhaps trying to do too much in the process as he never achieves a consistent tone. Even the musical numbers, supplied once again by Cafferty's Beaver Brown Band, are muddled, mixing in ill-advised "alternative" riffs and textures into the Cruisers' straight-ahead rock sound. The result is a soundtrack that sounds as confused and lost in time as the movie itself. Even Eddie and the Cruisers fans would be better off saving their money for Bob Seger tickets.

-JW

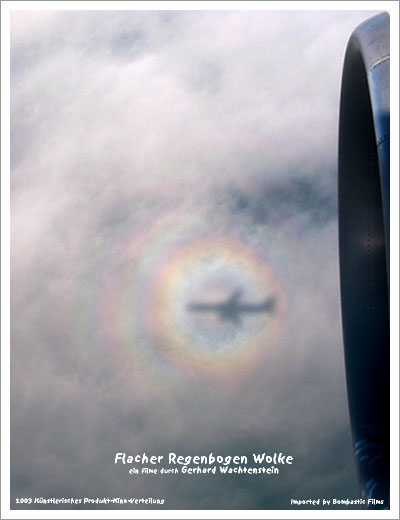

Flacher Regenbogen Wolke

(K�nstlerisches Produkt-Cinematic Verteilung, 2003)

Andy Warhol's film work is legendary. His films are almost the opposite of his mass-produced pop art canvases; where the latter are immediately accessible and now nearly ubiquitous, the former are difficult, challenging pieces that are almost never shown. For some good reasons -- who wants to sit through eight hours of a static image of the Empire State Building, or another eight of someone sleeping?

But there is a certain meditative beauty to Warhol's films which can only be accessed by waiting through the drudgery and breaking through to the other side. One becomes hypersensitive to fine detail: the rhythm of the sleeper's breaths, the rise and fall of a small corner of the sheet. It leads the viewer into a sort of zen state, painful and austere but with heightened senses.

Such is Gerhardt Wachtenstein's Flacher Regenbogen Wolke, or "Plane Rainbow Cloud." The German achieves a similar zen fugue state with its relentless portrait of the shadow of an airplane against the clouds below, shot from the window of the aircraft on a flight from London's Heathrow Airport to Budapest, Hungary, on a particularly overcast day.

Devoid of the contextual roar of the engine (Wachtenstein's seat was just ahead of the wing; the gaping maw of the engine is a constant presence on the right side of the screen) and hiss of the cabin pressure, the viewing experience becomes focused on the blurry figure of the jet. It bounces across the clouds, sometimes disappearing only to reappear once the clouds reform ranks. The rainbow of the title comes from the circular prism effect that accompanies the plane's shadow whenever the sun shines.

Named for the order in which the viewer's eye processes the subject matter, Flacher Regenbogen Wolke is a challenging improvement on the Warhol ouvre at which it so clearly takes aim. One could easily get lost in the subtleties of the cloud formations and their various effects on the airplane's rainbow halo. At 198 minutes, however, this exercise grows tedious quickly -- though it is far from the punishment of the eight-hour-long Empire. Wachtenstein's camerawork is mediocre at best -- though under the conditions very little could likely be done to improve matters -- and it's saying something that the audience releases an audible sigh of relief when he briefly puts the camera down to accept a beverage at minute 142.

Crowds will not be flocking to this film, showing this Wednesday at 8pm at the Storefront Gallery, 4209-B E. Newsome Ave., but those who do will be rewarded for their time. At the very least, they'll have a more comfortable nap than Wachtenstein's seat neighbor.

-AH

The Velvet Temptress

(Sappho Productions, 2003)

Pornography aficionados everywhere, take note! This might be the only time I ever review a "Skinemax" movie, but never has one deserved regaling as much as The Velvet Temptress.

Most late-night pornography adheres to certain staid conventions: balloon-breasted female stars, outrageous settings/situations, minimal plot and dialogue, and a criminal use of beauty products. But not The Velvet Temptress. Where other porn auteurs sketch a nominal plot out on a latte-stained Starbucks napkin, the origins of this film are decidedly more auspicious. Beth Atlanta was a student in a Harvard playwriting workshop when she wrote the first few scenes of The Velvet Temptress, and after moving to Hollywood she developed her effort into a full-length script. Miramax expressed initial interest, but Atlanta failed to sign when she heard the Brothers Weinstein's ultra-misogynistic suggestions for the film. Eventually, Atlanta raised enough capital and assembled an all-female crew and began the film herself.

The title comes from the female-only social club where the film is set. Doll (Cassandra Owens) owns the Velvet Temptress, approves new members, and breaks all the rules first. The club exists to stimulate and satisfy women's sexual desires. Showgirl waitresses strut about topless amid throngs of women amazed at sexual demonstrations and displays. Each Friday night, Doll starts the night's festivities by showing off her latest Toy, her term for the young women with whom she has short-term flings in the club only. But her latest Toy (Birgid Foster) is too engaging to let go. Through their evolving affair, jealousies emerge from Doll's inner circle, threatening the Velvet Temptress. The movie culminates in an S&M demonstration featuring Toy and Doll's second-in-command and former lover, Athena (Anne Bannon). Athena takes it too far and Doll must rescue Toy without destroying the Velvet Temptress.

In less talented, less devoted hands, this plot could easily disintegrate into mindless girl-on-girl sex set to the beat of an over-active wah wah pedal. But under Atlanta's direction, the cast extracts wit and intelligence along with sexuality from the material. Especially brilliant is Foster's portrayal of Toy. With only a few lines but a wealth of screen time, Foster projects a clear sense of the character while remaining lickably sexy. Ultimately, The Velvet Temptress main theme -- how women can suffer more at each other's hands than at a man's -- is as clearly expressed in this movie as it was in films such as "Working Girl." This sexual power play is a must-see.

-SB