Sixty years ago, surrealist painter Rene Magritte explored the vagaries of language by replacing images with words. If a picture was worth a thousand words, was the reverse also true? Magritte's word paintings were deceptively simplistic. They typically involved an amorphous white object with rounded edges framed in wood. In this object was painted a single word or description. These wood-framed blobs were carefully painted in a flat style into a simple setting -- usually on a hardwood floor and resting against a bare off-white wall. One of my favorite paintings has the words "Sad Girl" (in French) painted in a kidney-shaped object resting quietly against a bare wall. The idea was that the words that described the girl would supplant the image of the girl.

Of course they didn't. The words only suggested the idea of the sad girl. But the painting, as a whole, didn't depict a sad girl. You were left to your own assumptions about the sad girl; you were left to fill in the blank, so to speak.

These paintings weren't failures. They were careful studies of the limitations of spoken and written language as they applied to the evocation of imagery. The limits of which were even demonstrated in the first paragraph of this article. Unless you were familiar with the imagery -- the actual painting or a similar work by Magritte -- you've only got my vague description of the picture to go on. When comparing the actual work to your mind's image of it based on my description, it's a certainty that your mental picture will differ from that of the real thing.

In the name of specificity, and in an effort to do justice to Magritte's brilliant work, I could spend an the next 3,000 or so words describing for you the colors that Magritte used to paint the wood floor, the tediousness of the woodgrain that he recreates in both the floor and the frame, and the off-white -- almost aged-yellow -- color of the wall. It could get really damned specific -- the unnaturally forced perspective of the painting is evident in the floorboards that narrow, at their sharpest, to a seventy-degree angle. If that's the actual angle of the sharpest visible floorboard. I'm just guessing here.

The point is this: no matter how specific I get, you're still not going to see the image. You have to experience it for yourself, visually, to truly perceive the image.

Why is this important, you ask?

Because we are consumers, and we want to know what to expect when we consume. We all know that time's preciousness is determined by the very fact that we experience two points of reference that determine our time on this earth. There are countless adages that reinforce the notion that time should not be squandered, that life is precious, and that we should lead rich, productive lives. These concepts aren't new to us. We've always been consumers of one fashion or another. Of wheat and work. Of power and influence. Of sex and raw eros. We are visceral beings. We thrive on life. And artworks of any kind are a rich facet of the actions we collectively call "our lives."

(Did you notice that, in that writing, you understood exactly what I was talking about? Conceptually-speaking? Language functions beautifully, with great specificity, in describing the transactions of action and ideas. Just something to think about as you read this article.)

I recently picked up The Decemberists' record Castaways and Cutouts. I'm a huge fan of the band Neutral Milk Hotel and the comparisons between The Decemberists and the Neutral Milk Hotel excited me. I've experienced a deep craving for new or similar material since the NMH fizzled after The Aeroplane over the Sea. Could The Decemberists be my answer?

Sadly, no. No new Nuetral Milk Hotel fix for yours truly. Aside of from The Decemberists' greatness (and they are great), they're nothing like the Neutral Milk Hotel. What the hell went wrong, then? Why was I so misled?

In a word: ineptitude. The criticism I'd read everywhere from PichforkMedia.com and Spin to the blurbs posted on the record bins at Reckless Records failed in their attempts to impart on me a taste of the music I was about to consume. This time, I didn't leave disappointed. But I've been so in recent weeks: the new Basement Jaxx record has left me out 15 bucks. And in spite of favorable reviews, I wasn't a big fan of Cursive's most recent outing. Ditto for Dido. Am I going to force you to agree with me that these records are bad? No. Not really. Partly because they're not that bad. And mostly because it's just my experience with the music. Yours could be totally different.

I'm pretty diplomatic that way.

Most music reviewers aren't.

Eighteen months ago, Gapers' Block editor Andrew Huff and I made a cross-country trek to deliver me, my cat, and my cargo to beautiful San Diego, California. While on the stretch of highway connecting Springfield, Illinois to St. Louis, Missouri, Mr. Huff and I discussed the state of popular music criticism. Topics ranged from our favorite bands and records at the time (his: Twilight Singers' debut album; mine: Beck's Sea Change) to the very nature of criticism itself. Our discussions led to the creation of our Rock Crit blog, which we've been ignoring hard-core for the last few months. It started out with such great intentions. It just didn't go anywhere. Like a lot of da Vinci's work. (Dare I compare Andrew and myself to da Vinci? Why the hell not? Let's be ambitious, shall we?)

But to return to our topic: the intent of our blog was to explore the limitations of music criticism as it stands today and to suggest solutions to the dilemma that music critics and consumers of music criticism are faced with. That dilemma is three-fold: helping consumers to make quality music purchase decisions that fit their tastes and interests; educating a listening audience in the language of music crit's expression and opinions; and honing the craft of music crit as an art form in and of itself.

Contemporary music crit has succeeded only in the latter. I don't know about you, but I love reading record reviews. They seem so erudite, so witty, so carefully crafted to impart� what? Well, in a word, cleverness. The author wants to show you just how witty, well-learned, and clever he or she truly is. That's all well and good -- art for art's sake and all of that -- but it's utter bullshit when it comes to helping consumers make decisions and educating a listening audience in the descriptive language that successfully describes the music the reviewer is attempting to review. In the first case, I'll tell you what I as a consumer want: I want to know if the new Ani Difranco record is worth listening to. Let's face it: her output has been uneven in recent years. I love her voice and think she's a talented songwriter and brilliant lyricist. There've just been a few of her records that I've wished I would've skipped rather than shelling out 15 bucks for that I would later sell at Disk-Go-Round for five. And I don't want to take a 66 percent loss in this particular music-purchasing gamble. What I want my music criticism to tell me is whether or not I'll like it.

But music criticism can't do that. A review of Difranco's new record will probably draw comparisons to previous outings (in this case, her earlier work, because on this recording she's getting back to her roots -- it's just her and her guitar, after all), explore the influences on her current "sound" and lyricism, and make some kind of statement of the record's place in both her oeuvre and in the canon of popular/jazzy/rockish folk music as a whole. But would that tell me anything that'll assist me in my purchase? Hell no. And why is that? Well, there are two reasons.

The first is obvious: record reviewers are either writing to a broad audience or to a narrow audience. In either case, the review probably isn't aimed specifically at you as a consumer and, as such, isn't necessarily going to persuade you in one direction or the other. Granted, a reviewer can't crank out reviews suited to every individual. But neither the review aimed at a general audience nor the narrow one is necessarily more helpful than the other. Broad audience reviews have obvious limitations: the author is writing to the lowest common denominator and attempting to describe a record to everyone in terms that are easily understandable by all. This leaves individual readers with a vague sense of what the record might sound like and is about, but it doesn't get them any closer than that.

Narrow reviews hold more promise, but they still get it wrong. They certainly have the virtue of aiming themselves at a more specific, probably more knowledgeable audience (at least in terms of the artist of genre) than the big reviews do. And by that, they are actually helping a select few make some purchasing decisions. But the greater population gets left behind in the shuffle.

I know, I know, I just assaulted broad-audience reviews for being too general and not very helpful to the individual. But narrow reviews aren't helpful to most individuals, and here's why: a reader has to go hunting through multiple publications to find a review that's aimed at him or her. And it's not like every publication is going to be one that any specific reader will implicitly trust. As a rule, I tend to be a PitchforkMedia.com reader; however, Pitchfork leans toward the indie rock/emo-punk end of the spectrum and as such regularly pans such records as Nine Inch Nails the Fragile and Tool's Lateralus, both of which I enjoy very much. So, no one publication's reviews can be the panacea for any one reader.

(There is a solution out there: MetaCritic.com compiles music reviews from various publications and scores and references them for easy comparison and consumption. It's worth checking out -- if you have time to invest in reading 20 reviews looking for the one that applies to you.)

The second reason music reviews won't help me make a music purchase is more complicated and points to my earlier assertion that one of the aims of music criticism is to educate its audience in the language used to describe music as an art form. Remember Magritte? Paintings and sculpture are easier for us to describe because the language we use to describe action and ideas contains words that are easily transferable to the description of lines, color, and composition that make up these art objects.

As nebulous as the concept of composition is as it applies to painting, most of us haven't the foggiest notion of what composition means when it comes to describing a song or a "concept record." While the language we reserve for the visual arts can't fully communicate the seeing of those works, the same language falls on its ass when describing music. That makes sense -- the concept of line, for example, between the two is radically different. Moreover, music is just a totally different animal. As such, we need a separate language to describe it.

The good news is that a language already exists that describes music. The bad news is that contemporary listeners and, I suspect, reviewers haven't a grasp on that language at all. I sure don't. And even if a reviewer correctly describes a work of music in terms of its codas, refrains, verses, arpeggios, and blah blah blah, would you as a consumer know what the hell he or she was talking about?

Even the most musically literate consumer is still screwed by the state of music criticism today. Again, most music critics are as deaf to the language of music analysis as the average Joe/Sally is. There is no musical equivalent to the educational process that your typical art critic undergoes -- or, if there is, most music critics don't go through it (with the probable exception of most classical and jazz critics). Most music critics are fans, primarily, and their enthusiasm or lack thereof is more evident in their work than any discussion of structure, meter, tone, etc. Consequently, the average rock review comes off like the excited and/or snide writings found in an erudite college student's journal -- essentially telling a reader in ornate terms that he or she thinks something rocks or sucks. It all boils down to this: music reviewers are even less successful in evoking the very sound of a piece of music than an art reviewer is in evoking the visual elements of the work they're reviewing.

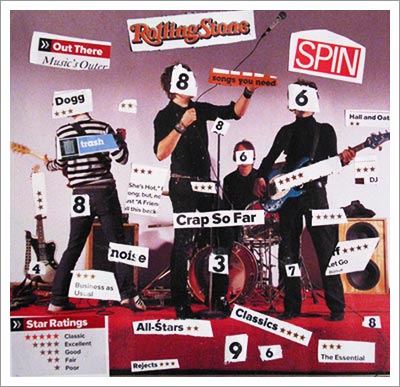

Music magazines tacitly acknowledge this limitation by resorting to a numbered, barometric scale of music's quality. You know the ones: Rolling Stone's five star scale; Spin's ten point scale; and the even more granular decimal scale used by Pitchfork. The idea of these scales is that they're supposed to enhance the reviews and provide you, the consumer, a better sense of whether or not you're going to like the music you purchase. Like every other aspect of music criticism, though, they falls flat on their faces.

I resort to an allusion to Dead Poets' Society here. Remember the J. Evans Pritchard scale for measuring a poem's worth? The good doctor asserted that you could plot a poem's perfection and importance on the x- and y- coordinates of a graph. The total area achieved by the evaluation revealed the poem's overall greatness. I don't remember if Robin Williams decried it as hokum or horse puckey, but it stinks of bullshit to me.

The same can be said of the numeric scales used to evaluate music. Lets take the example of RS's five-star rating system. Anybody remember what it used to mean? Four stars were reserved for the very best in music. That's right: four stars. And what did RS reviewers award five stars to? Classics, or records so unfathomably brilliant as to be instant classics. In spite of the fact that RS's current incarnation has totally lost any semblance of perspective in its rating system (how many five-star ratings are awarded per issue these days, anyway?), even when it was good, the rating system still didn't help most consumers make educated decisions about any record purchases other than those of the most popular of pop music. The benchmark was literally set by the Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, Bruce Springstein, and U2. And lets face it: the Stones haven't had a great album in decades and U2 jumped the shark during the first leg of the Zoo TV tour. So stop awarding them five-freakin' stars already. Bono could sneeze and it would trigger an excited blip on the RS radar.

But I digress. It's not just the five star ratings that are skewed in the Rolling Stone rating systems, either. A disproportionate number of three and four star reviews are thrown at consumers on an issue by issue basis. At first blush, a reader/consumer might assume that RS just doesn't publish reviews of shitty records. In some cases, this is probably true. But read many of the three and four star reviews that have made it into the hallowed pages of Rolling Stone more closely and you'll discover something troubling. While a record might be rated a three, the actual review of it seems to indicate that the record is mediocre -- at best a one star album.

The discrepancy between the review and the rating is alarming -- one that has an obvious explanation. The editor sets the star-rating for an individual record independent of the critic's review. The lowest common denominator, here, is looking primarily at the stars awarded to a record and probably doesn't even take the time to read the review. This is what the industry-driven publisher is after: sales driven by positive record analysis. But this compromises those consumers who want more from their music than the latest Janet Jackson single. The consumer wants to know what to take away from a music review whose barometric scoring says the record's a worthwhile investment while the written portion indicates that it should sold in the discount bins at Tower. The consumer is hungry to find good music. And mom is saying one thing about a record while dad is saying another. Here the rating/written review marriage fails.

In lieu of educated, educational descriptions of the sound of a passage of music, most music reviewers resort to two half-assed methods of music description. The first involves describing the qualities of the instruments and sounds that make up a song or record. How many times have you read the phrases "searing/spiraling guitars," "kinetic drums," and "thundering bass" (or similar) in a record review? What, exactly, do those mean, and what do they conjure in your mind? Do you know exactly what a �thundering bass line� sounds like, especially when the term is applied to everyone from Flea to Geddy Lee?

The second is to employ our knowledge of other bands' music to describe the band-in-question's music -- in terms of sound, songwriting, and style. Reviewers often resort to this tactic in order to come closer to defining a record's sound, that elusive quality that, hopefully, sets the band apart from all others. Liz Phair's recent outing could be compared to the last few records by Sheryl Crow. Radiohead's Hail to the Theif has been compared by Spin authors to the band's earlier works, having been called a culmination of everything from the Bends to Amnesiac. And let's return, shall we, to the comparisons drawn between the Neutral Milk Hotel and my recent purchase, The Decemberists. While these may be valid comparisons for the reviewer, the reader may not know the bands the reviewer is associating the band-in-question with. What's more, the comparisons a reviewer contrives may not make any sense at all. A reviewer may hear even the slightest something in the music that just happened to trigger the thought of another band for him or her. But does that mean that the same passage of music will do the same for you? I've read reviews of Make Up the Breakdown by Hot Hot Heat that suggested the band exhibits hints of The Cure, but I don't hear that at all.

Finally, we return to the one aspect of music criticism that is successful: cultivating music crit as an artform in and of itself. The best in music criticism is usually well-written stuff. It celebrates its author's grasp and knowledge of both popular and obscure music. And, most importantly, it's really persuasive stuff.

That's right: persuasion. Music reviews are, at their core, all about persuasion. But not in the light that you might think. One assumes that music reviews are designed to persuade a reviewer to make a purchase. But that's not really the case. Music crit is meant to persuade you that the critic's tastes are right and important and therefore you should base your purchases on their recommendations. That's harsh medicine, I know, but we can't reform music criticism as it stands today without being honest with ourselves about what it is and where it fails.

Music criticism fails because critics and their listening audience lack the necessary common vocabulary to describe and comprehend music. Music crit fails because as an artform it's totally self-obsessed. And music crit fails because it generally doesn't give listeners an accurate taste of what's in store for them if they do purchase the music in question, so it doesn't adequately help them make purchasing decisions that reflect their tastes and interests. (In fairness: services like Amazon.com that offer musical snippets for the music consumer to sample definitely assist the written reviews that accompany said music).

In short, the state of contemporary music criticism is that it's a complete fucking failure.

So what's a reform-minded critic of music criticism to do?

Well, the best possible solution would be for both reviews and readers of rock criticism to learn the language of music. I'm talking notes, melody, song structure, volume, tone, quality of playing, and more here, folks. Of course, there are serious limitations with this solution. The best option would be for music education to be offered as aggressively as fine arts are from grade school on -- by which I don't mean just instrument lessons but also actual music theory and appreciation. That way consumers and reviewers would have the same level of competency with regards to music terminology. (Not that they don't right now: collectively, we don't know jack.) But that's not going to happen under the No Child Left Behind era of education.

Another option might be for music critics to embrace point number two of the above discussion: educate the listening public on the language of music. I'm afraid that's not going happen, either. Most music publications aren't going to set aside a couple of pages each issue for passages describing tone, structure, and blah blah blah. Their readers are in too much of a hurry to find out if Justified is better than anything Justin put out with N'Sync (and it is) -- most of them are in so much of a hurry that they aren't even bothering with the written reviews anyway and are instead looking solely at the ratings. Advertisers want to pay for content that will be read by consumers. Engaging, sound-bite sized content ensures that short-attention-span readers will keep coming back for more. So that's what music magazines publish. Witness the rise of Blender, with its highly tauted 100-plus reviews per issue.

So that blows the whole educate the masses plan.

What, then?

Well, assuming that music criticism as a written art form is going to stay the same as I concluded earlier (and it probably will), we could reform the numeric rating systems that accompany the articles. That's right, the very barometric tool I dissed royally a few hundred words back. How, you might ask, would we go about doing this? And how might we trust that a modified music rating scale might be an improvement over the status quo?

Setting the bar appropriately is one way of giving a music consumer a sense that a barometric rating scale reflects their tastes. If Spin were to say, "a seven is about where the White Stripes' Elephant falls and a ten is where any Radiohead record falls," you might get some idea of how their ratings scale is benchmarked. But that presupposes that you are familiar with the White Stripes and Radiohead. If you aren't, you're out in the cold.

Believe it or not, I'm kind of a fan of Amazon.com's customer rating scale -- in principle. Granted, every schmuck in the world has a voice in reviewing a record on Amazon or a similar eOutlet. And those schmucks all get to assign said record a star rating. But it's highly democratic. Everybody's voice is heard.

There are a couple of problems with the system, though. Firstly, allowing the star rating to be driven solely by consumer reviews is a real problem because there are only two types of consumers who go out of their way to write a record reviews on Amazon: those who really liked the record and those who couldn't stand it. Both feel strongly enough to share their feelings on the subject. And both severely skew the scale of the review -- mathematically speaking, there isn't a true middle rating in the Amazon scale. There are tons of positive reviews. There are a couple of extremely negative reviews. But there are almost no reviews in the middle ground. Consequently, the median rating is severely skewed in either highly subjective direction along the numeric scale.

Secondly, there's the element of time. In order to get a number of record reviews under the Amazon belt, at least five and probably 20 people need to take a risk on that record and buy it either without prior indication of the record's contents or with some knowledge garnered from standard rock criticism -- and you know how I feel about that. Also, music crit strives to be written in a timeframe contemporary to the release date of the record. It needs to be fresh if it's to mean something. And how many of Amazon's consumers actually get to listen to the record prior to its official release date?

But I still have faith in a modified consumer rating system. So here's my proposal.

Create a stable of volunteer consumer reviewers and ask them to review something like two or three records a month in exchange for five free CDs of their choosing. (That sort of compensation is no sweat off a major label's back.) Then, for each record to be reviewed, select 20 volunteers from your stable, send them advance copies, and then get their numeric ratings. Average your consumer ratings. And voila.

Which ratings scale would I propose that we use in conjunction with the volunteer consumer review process? Well, I'm opposed to the Rolling Stone five star method because it's too broad, too easily misinterpreted, and not sensitive enough to really rate a record in any meaningful way. On the other end of the spectrum, Pitchfork's 10.0 decimal scale is probably too fine-grained. It's one thing to say that anything that falls between a 9.5 and a 9.9 is spectacular, but why do we care whether it's a 9.7 or a 9.8? Does that level of detail actually help us in making our music purchasing decisions? No, but fortunately it doesn't hinder us, either.

I'm thinking that a 10 point scale, such as Spin's, probably offers the best of all worlds here. It's sensitive enough that there are distinctions between the ugly, the bad, the good, the great, and the utterly amazing. But it's not so granular that we lose track of those distinctions, either. Moreover, a 10 point scale is easier to use in terms of aggregating reviewers' scores into a composite review.

Those of you with mathematic inclinations might ask me which averaging method would be best-suited for building a composite review -- mean, median, or mode. In this case, I'd recommend a strict mean (i.e., simple) average -- totaling the reviewer's ratings and then dividing those by the number of reviewers to reach a composite score. Round up or down to the nearest whole number and you've got yourself a rating.

Admittedly, such a scale is not perfect. It only gives a general idea of what people thought of the record. And like any statistical sampling, it's greatly influenced by the qualities of the population that reviews the record. If the randomly or even non-randomly selected 20 reviewers were all fans of similar genres of music -- let's say indie rock -- you're not likely to get a positive review of the latest speed metal record. And that's not very helpful to speed metal aficionados.

We could also open the ratings system up further. Once the original review and ratings are published, we could (and probably should) open the review up to additional consumers and allow them to positively and negatively influence the record's rating along the numeric scale. That, combined with their individually written reviews, might give us an even better indication of the likability of the record.

But even that fails. The consumers still need to take a risk on the record and assume that the modified rating is an adequate reflection of their own tastes. They have to care enough about the resulting purchase to write about and rate it. They have to do a ton of legwork and reading to process the music reviews/ratings prior to making that purchasing decision. And such an improved rating lacks the timeliness of a review that is contemporary to the release of the record.

So, bring in the clowns. It's time to bring the professionals back into the mix. For better or for worse, the pros offer a more refined perspective in the review of music, if only by virtue of the fact that they've just plain listened to a lot more of it than you and I have. And whether or not their reviews are truly helpful, there is a certain degree of trust that is placed on the assumed authority of the professional reviewer.

To make this work, we have to take the collective opinions of the music press -- such as the composites offered on MetaCritic.com -- and factor those into the final number. Give the "professional" reviewer's scoring of the record a certain weight, give the totality of consumer reviews another weight. I'm thinking something like 30 percent and 70 percent respectively, or maybe as high as 45 percent for the pros. We then create a more sophisticated basis for the rating.

Couple the rating with a review that is complimentary to it, and you've got something. The rating shoots for the broader end of the consumer-purchasing spectrum, while the written review narrows the field a little bit and gets into the nitty-gritty of the record, and also preserves the artistry of the written review.

This modified result isn't perfect, but it's a vast improvement over the status quo. Now if only we could work music education into music criticism.

QPG / February 6, 2004 8:43 AM

Very interesting article. A lot to digest! Very thought provoking. I'd give it a 9.0 and say its definitely a "new classic".

Great article!

Q

(my comments get a 5.3)