| « Ready for Beer Bingo? | Lillie's Q Bucktown Scheduled to Reopen Mid-June » |

Gardening Wed May 15 2013

Should You Grow Vegetables in Chicago Soil?

Recently I caught the green thumb. There is something so rewarding about growing your own plants. Germinating the seed, watching the fruition of life day-by-day, and then devouring the fruits of your labor. I decided to use the space in my new backyard to grow a humble vegetable garden. I ordered some organic seeds and began the process. As my babies grew and demanded a bigger space for their roots to spread out , I began to dig up my patch of dirt and check out the soil.

Recently I caught the green thumb. There is something so rewarding about growing your own plants. Germinating the seed, watching the fruition of life day-by-day, and then devouring the fruits of your labor. I decided to use the space in my new backyard to grow a humble vegetable garden. I ordered some organic seeds and began the process. As my babies grew and demanded a bigger space for their roots to spread out , I began to dig up my patch of dirt and check out the soil.

Uh-oh.

It looked like a family picnic was buried in my yard. I pulled out a small action figure, a broken plate, a tennis ball, piece of a Frisbee, shards of beer bottles, bricks and countless rocks. After talking to a gentleman with some knowledge on the subject at a local grow store and realizing my soil was battling the elements, I had some doubts if I wanted to even grow my plants in the ground.

I have heard some paranoia on the subject of growing in Chicago soil based on its industrial past, heavy car traffic and its old, ever-changing landscape. It was suggested that I could get my soil tested to see if I had any harmful chemicals residing within.

In a study by the University of Illinois (2011), 10 gardens across Chicago grew lettuce and tested the crops for traces of the element lead. In most gardens the levels of lead was not a health concern. But I was still worried.

The College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Cornell University suggests testing your soil "for heavy metal and nutrient levels at least every two years. Certain chemical elements occur naturally in soils as components of minerals, yet may be toxic at some concentrations." After I dug up a soil sample (6-8 inches deep) from my plot, I headed to Stat Analysis in the Tri-Taylor area, a laboratory capable of testing my soil.

If you do test your soil, it is up to you to choose which elements to check for at the lab. I tested my sample for arsenic and lead, which can be harmfully prevalent in many urban soils. Both of these elements are #1 and #2 on the Priority List of Hazardous Substances on the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). But don't be too paranoid, trace levels of arsenic and lead occur naturally in all soils and it is impossible to grow plants completely free of either. You just don't want abnormally high levels.

A down side to testing your soil is the process can become very expensive. When you run a "comprehensive" soil test Stat Analysis charges a base fee (of $40) then an additional $10 for every other element after that. A wide analysis of everything in your soil can become costly. Most urban growers are concerned with "heavy metals," especially arsenic and lead; some studies [PDF] suggest the elements cadmium and barium may also be prevalent in urban areas.

When in doubt, bust the pots out.

If growing in the soil is not worth your time, money or labor -- screw it! Save your money and just grow in some containers, whether hanging or on the ground. It is a easier way to control the soil and nutrient intake of your plants.

But I dug up my dirt and want to put my plants in the ground, dammit!

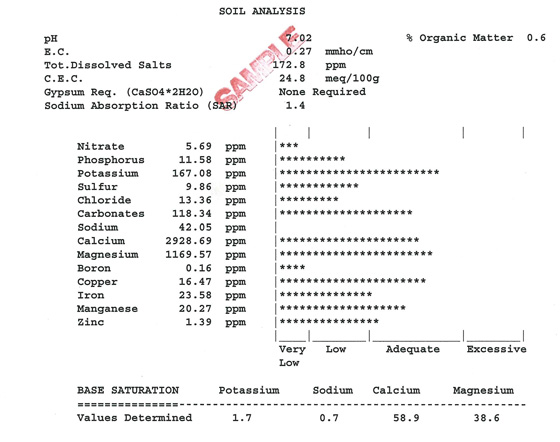

When you do receive your analysis from the lab, don't be overwhelmed by all the numbers and abbreviations. It will include the some helpful information like the acidity of your soil (ideal pH levels should be around 7), the levels of nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus in your soil (your plants favorite nutrients) but also the levels of special elements you tested for. All elements on the sheet will be measured by parts per million (PPM). Which simply means for every million 'parts' of soil by weight, there is 1 part of the chemical being measured.

This is where things are sketchy, because there is no health-based standards in the United States when it comes to the amount of metals in community gardens.

Hence its just us urban growers trying to find a medium of tolerable exposure. The recent study from Cornell University discuss using EU (European Union) standards and suggest "tolerable lead levels should be around 400ppm and arsenic around 20ppm."

If you are below or near the medium level, congratulations! This is good news -- your exposure to these chemicals is at a normal level and nothing to cause alarm. But if your chemical levels are substantially higher (like mine were), let's have a chat. Don't freak out.

A Short History of Toxins

Lead is a metallic element found everywhere in the human environment, especially since industrialization. Although it was quite useful as a gasoline and paint additive, it has no physiological use in humans. From neurological effects to miscarriages, high exposure can negatively affect our health in a number of ways.

In a background study from Washington State University, (Peryea, 2001) lead in home garden soils was found to usually originate from paint, gasoline, insecticide and industrial fallout. For us Chicago-based growers, be cautious if your home was built before the '70s (lead-based paint wasn't banned until 1978). Flaking or chalking of lead-based paint can create rich dusts that may have fallen in nearby soil. Lead concentrations are higher in soils near heavily used roads; as Peryea states, "oil companies used lead in their gasoline up to 1995 when it was banned nationwide. Seventy-five percent of all lead particles were emitted from exhaust pipes decades ago [and] now may be settled onto nearby soil."

Our friend Mr. Arsenic is everywhere in our environment as well. Be cautious if you live in an industrial area, one with smoke stacks, since arsenic and lead are released as a gas during the combustion of fossil fuels. Peryea believes this is a red flag if your garden is within 1 mile of "existing or former smelters, fossil fuel-fired electrical power plants, or cement manufacturing facilities." He also suggests to avoid self-contamination by avoiding "use of railroad ties, telephone poles, pressure-treated wood and previously painted wood to build your [garden] beds because they contain chemicals that can migrate into soil."

Plants are very good at taking elements and nutrients out of the soil -- that's what roots do. However, the relationship between soil and plant varies so much, it is impossible to predict accurately how much of the element a plant will actually absorb.

Still Making Use of Your Soil

My home garden is in a rough spot. Not only is it near a main intersection, it is also a stone's throw away from highway 90. And to make matters more interesting, I live in a old building which was built in the '70s and I couldn't rule out lead-paint flaking.

But I wasn't going to give up the cause.

My soil contained slightly more arsenic and lead than EU standards recommended. But, there are still plenty of preventative measures to combat slight contamination of your soil. If your soil is highly contaminated (like three times the standard PPM), maybe you shouldn't risk growing food in the ground.

Anytime you can use fresh soil rather than the soil that's already there, its far more favorable to work with. Don't make the rookie mistake I did by tilling your soil immediately. Professor Peryea suggests getting rid of those first 2 inches of your soil, which could be the most contaminated parts. Tilling the ground may actually make it worse, "by distributing the more contaminated layers of soil evenly and deeply."

Another great alternative, is making a raised bed for your garden. A raised bed is simply an elevated extension from the ground, made out of virtually any (non-toxic) material to simply put some distance between your ground soil and the base of your plants. In the Chicago study, which surveyed some community gardens growing leafy vegetables such as lettuce, "use of raised beds significantly reduced lead levels and therefore less potential risk of lead ingestions from plant uptake." Raised beds simply give your plants' roots more room to work with, which can reduce the absorption of the more funky stuff laying deeper in your soil.

Another suggestion is growing several fern plants around your garden area. These preventative plants are good at soaking up contaminants out of the soil. Through the process of phytoremediation, lead and arsenic can be absorbed through the plants roots into the leafy fern leaves where the metals are stored. These plants act as leafy sponges. You then can simply cut the leaves off which, will help reduce the chemical levels in your dirt.

Even if your soil is below the average tolerance level of metals, wear gloves when interacting with soil, or always wash your hands after dealing with your garden to reduce exposure to the chemicals. Do not touch your face and stop children from playing in the soil since they are more susceptible to health risks.

Reaping the fruits of your labor

When you have finally cared and nurtured for your soil and your crops finally grow, remember to thoroughly wash or peel your vegetables to limit your exposure to chemicals. The contaminants will wind up on the outside of your crop, the parts that were exposed or caked in soil.

The best way to limit your exposure is to select vegetable crops that are less likely to have contaminants on or in their edible parts. If metals are a concern in your garden, you could consider growing only fruits or vegetable fruits, such as tomatoes, peppers, eggplants, squash or peas.

Chemicals in the ground are more likely to be absorbed by the leaves of the plants. When dealing with leafy plants (lettuce) or root crops (carrots, potatoes), remember to wash your crops thoroughly. These crops are simply more likely to be exposed to harmful chemicals. You could always peel away the outer layers of the vegetable or consider throwing away the outer leaves of your head of lettuce or cabbage.

In any case, it is better to be cautious than to be ignorant of what may be absorbed in your vegetables and eventually put into your body. Although the ground in my backyard seemed to be a battleground of human litter and metallic chemicals, I'm still confident that I can grow a safe vegetable garden in my Chicago soil. By testing my soil, completely getting rid of the old soil, tilling in organic materials (soil and compost), and making a raised bed, I am no longer worried about what veggies I grow in my garden.

For more information on urban gardening:

• Cornell University Guide

• (Peryea) Growing on Arsenic and Lead Soil

Shylo / May 15, 2013 4:27 PM

It's actually really, really irresponsible to recommend phytoremediation as a technique for reducing lead levels. It either 1) doesn't work 2) works so slowly that it's just not appropriate for residential applications and 3) creates its own waste.

In CA, the EPA is doing really good work with using fish bone in lead-contaminated soil, which binds with lead, rendering it inert.