| « Friday Foodporn: Quiche | Cooking a Better School Lunch » |

Interview Mon Nov 04 2013

More Interested in True Creativity: A Conversation with Grant Achatz

Illustration by Dmitry Samarov

Considered and labeled by man as the greatest chef in the United States and one of the finest and most respected in the world, 39-year-old Grant Achatz has been at the forefront of molecular gastronomy (or as he likes to call it "progressive") cooking since he opened his world-renowned restaurant Alinea in 2005. In just a few short years after Alinea's opening, it was declared the finest dining establishment in the country and one of the top 10 in the world.

Before opening his own restaurant, Achatz worked as the executive chef of Trio in Evanston, and before that at the French Laundry in Napa Valley, California. Although Chicago was certainly a food-oriented city prior to Alinea coming into being, it was mostly about attracting customers from the suburbs to drive down into the city on the weekends. But since Alinea, the city has now become world travelers' destination if they are interested in fine dining. In more recent years, Achatz has expanded his empire to include Next (which opened in 2011), a restaurant that changes the theme of its cuisine every three months, and the adjoining bar the Aviary, in the city's Fulton River District.

But perhaps Achatz's greatest accomplishment was overcoming a 2007 diagnosis of stage 4 squamous cell carcinoma of the mouth, an affliction that at best could destroy his ability to taste, and at worst would kill him. But thanks to an aggressive chemo and radiation regimen with doctors at the University of Chicago, Achatz announced that he was cancer free at the end of 2007, without having to have invasive surgery on his tongue and without losing his sense of taste.

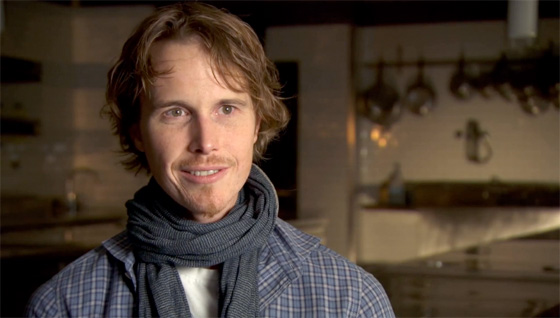

In the new documentary Spinning Plates (currently playing at the Landmark Century Center Cinema), Achatz and Alinea are profiled alongside two other very different restaurants (a country-dining establishment in eastern Iowa and a Mexican restaurant in Tuscon, Arizona), with the common theme being that all of the owners went through incredible hardship to get where they are today. From director Joseph Levy, this remarkable film has Achatz walk viewers through his cancer scare and recovery, as well as through Alinea's space-age kitchen.

Still from the film Spinning Plates

I was fortunate enough to have an extended conversation last week, via phone, with Achatz about the film, his way of looking at the world, his thoughts on the glut of cooking-related reality shows and documentaries, and the things in his life he focuses on outside of the kitchen.

Have you seen the finished film, Spinning Plates, at this point?

I have.

What did you think of the other two segments in the film and those people?

I felt like last night in particular at our final premiere party it was very telling where the entire Breitbach family [owners of Breitbach's Country Dining] came all the way from Balltown [Iowa]. There were about 12 of them, and they all piled into a van, and it was really neat to actually meet them. And we all kind of had one of those revelatory moments where, like I say in the film, Alinea can be a place with really long menus that involve science, trying to shoot for the stars. But you can have a country diner or La Cocina De Gabby in Tuscon, but at the end of the day, we're all restaurants.

That's one of the things Mike [Breitbach, owner] said. "We're in a town of less than 60 people population. We were a little bit worried coming here because of your notoriety and how many people live in Chicago. We were a little intimidated, but once we got here and met you and your team, we were immediately at ease." And I looked at him and said, "We all do the same thing. We just take different roads to get there."

I grew up in a restaurant that's almost a carbon copy, with all due respect, to Breitbach's. My grandmother owned a family diner in Michigan that had a population of about 1,100. My father opened a restaurant in Richmond, Michigan, with about 750 people. I worked my way through all of those restaurants; I understand. That's sort of the foundation, in this weird way, of what Alinea, Next and Aviary are. It's food at a certain level, but it's hospitality at the same level.

So it was really neat to see, and I thought Joseph [Levy, the film's director] did a really good job directing the film and weaving three very distinctly different restaurants into the same thread. I think that surprised people in a lot of way, seeing how Gaby and Francisco unfortunately lost their restaurant, and the Breitbach's burned down twice, but they're still going. But honestly, it's incredible how similar they can be no matter the style of cooking they are. At the end of the day, not matter what, we're here to nurture people. It's about bridging three individual restaurants and the people who are running them and exposing the creativity in their individual worlds and overcoming whatever adversities, whether it's the restaurant burning down, financial woes or a life-threatening illness. I thought he did a really good job and tied it together really well at the end, with my narrative going over their visuals.

That juxtaposition of your narrative about your youth in your family's restaurants and showing these other two kitchens, it tied is all together nicely. I'm guessing you get a lot of requests in a given year to film in your kitchen, and I know that you and Joseph had worked together on something a while back when you were at Trio. But I'm wondering how he approached you to be a part of this documentary.

You're absolutely right. We've been fortunate enough because of our popularity in gastronomy or because of the originality of what we do and the way we approach it, we have had a lot of requests. And I will say that some of them that we've said yes to have gone very poorly, for whatever reason. We had a film crew in that felt like they were doing us an immense favor by giving us publicity, and they lit our dining room carpet on fire because they short-circuited one of their extension cords for the cameras. And they didn't say "Sorry." It was like, "Hey, that's all part of the thing, the price of doing business." And we're like, "Not really." [laughs] Maybe in Hollywood when you guys work on sets, but not in restaurants.

But with Joseph, when he did "Into the Fire" at Trio back in 2003, you form that bond of trust. And he always understood that there were moments during the filming where you have to be a fly on the wall and get your team pulled back to let the restaurant do its operation. But there are also moments when you can get right in our faces and extract those emotional components to make a film great and special. And he had that knowledge; he did that really well. So we became friends and he ate at Alinea a few years back. Then out of the blue, he approached me and said, "I want to do a documentary on a bigger scale and put it in theaters instead of just on a network. Do you mind if we delve into a little bit about what you created at Trio but also what you've moved onto with Alinea, Next and Aviary?" And I said, "Absolutely. I trust you and your team." One of the videographers and one of the sound guys were the same that worked on "Into the Fire." And we all got to know each other and trust each other.

A clip from Spinning Plates featuring Alinea.

My most proud emotion for Spinning Plates is that I feel that it's very honest. We stay stuff in there that isn't all that guarded, and the reason for that is that we trust that Joseph would edit well, would uphold our personalities. He put a lot of stuff on the cutting room floor that I'm glad he did. [laughs] But if he had not have, I would have been okay with that because we were comfortable telling him that on film. You rarely get that relationship with someone who has a camera in your face and you know that whatever they're recording could go on Netflix for the next 10 years. It could really be a big way that people perceive you and your restaurant and your personality. And he knew that we were going to be very forthcoming, which would make it a very compelling story. He knew that I wasn't going to go in there and say, "Yeah, I don't really want to talk about cancer," or "I don't really want to pull the curtain back on how we create food." He knew I was going to tell him what I thought and how it is. It was a great synergy.

Did you know in advance that Joseph was going to dig so deep into your personal life — your cancer scare and your family history? It really does make for a well-rounded portrait of you.

I figured he would. He did a little for "Into the Fire," [but] it was a much shorter segment, it was channeled through the Food Network. And the food audience today is different than it was back in 2003. A lot of people have said to me that this truly isn't a food story; this is a human interest story. And I don't disagree with that for a lot of reasons. The bandwidth that we are now able to capture outside of the food world, literally talking about overcoming a life-threatening illness, or having a small community rally around a family to rebuild their restaurant two times. My goal would be that when this movie becomes more and more popular and hits that level of Jiro Dreams of Sushi, maybe there's a way we can set up a very simple website or a version of Kickstarter and we raise many so that the Martinez family can get a restaurant again. That's not just a documentary about cooking — not to take anything away from other food documentaries.

There are more of these food-related documentaries today than ever before. But you're right, there has to be an extra dimension to them than just shadowing a chef around in the kitchen for a few weeks to have longevity. Is this glut of cooking and food shows on television and movies a good thing in the long run for a business like yours?

At the end of the day, I think it is a good thing because it exposes cooking in a way that, more often than not, is good. For instance, late at night when I come home and end up on my couch at 2:30-3am, and I boil some pasta and throw a little olive oil, butter and parmesan on it and just want to relax after a 17-hour day, I'll flip on the Cooking Channel or the Food Network, and I'll watch Guy Fieri. I'll watch watch him do "Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives." Say what you will about his aesthetic and his personality, but when he's cruising around Memphis, Tennessee, going around to these great, family-run barbeque places, or in Detroit going to delis and talking about pastrami, I think that leads to a proliferation of people being interested in not only food but good food.

So "Top Chef," "Top Chef Masters," "Chopped," all those reality-based TV shows, at the end of the day, I stand back and think, if I were to ever do a cooking show — which we've been offered many, many times, and we've turned them down because it didn't quite feel right. But I feel like they're making people aware that nutrition and eating well are important, cooking in your home is important, and food in today's culture is gaining popularity and importance. We would do it differently, and we've been trying to do it differently.

On the downside of TV cooking shows, they're largely the same. Everybody wants scripted reality. You flip on the TV at any point, and it's "New Jersey Housewives" and the Kardashians. When I look at "Top Chef" or "Chopped," they're all cooking competitions with their five contestants and they throw them a curve ball and they have to dig their way out. That's okay, but why don't we come up with something a little different? Quite frankly, that's what Anthony Bourdain did that was good and different. Anthony and I have had our back-and-forths in the media. He said a couple of things about Alinea that weren't very flowery. [laughs] But at the end of the day, he did say that what Alinea has done for American gastronomy is all very positive, and whether I like his cooking style or not is almost irrelevant. The guy is taking risks, and it's an important part of the fabric. But his TV shows are also some of my favorite to watch, because what he's done is blended high-end Travel Channel or History Channel stuff with cooking.

I watched one two weeks ago where he travels to Tijuana, Mexico. He's kind of coarse; that's his personality, which is honest. I've met him several times; I know him. He's the type of guy that won't read from a script. "I'm just going to say what I want," which makes him feel genuine and honest, which I appreciate. But what he does that is cool is he travels the world, and as a viewer, you get to see them in Tijuana eating the best fish tacos that they can find. They do their homework and research, and they talk to the native cooks and the grandmothers, and it shows them sourcing that out.

With Andrew [Zimmern] and his show ["Bizarre Foods"], I think it started out, I think, with a producer or studio somewhere saying, "Why don't we do a show where you travel the world and eat gross stuff, like bugs and intestines." What ultimately happens is, Andrew being smart enough and being a trained chef, he goes, "We can do that because in gastronomy when you go to Australia or New Zealand or Africa, eating termites and grubs and ants is a way of life." So we can show people in America and Europe, where they think it's gross and it's not a part of their culture, it actually is in other cultures. Those two guys have done it in a really great way because they give you a 90-second dissertation on a place's history, when it was colonized, a bit about the food and spice trade, what stuck, what didn't. And then they dive into today and what is quintessential, present-day food from that place. They taste it and talk about it. It's not like, "Okay, you need to make a dish out a Cheetos, beef, peanut butter cups and whipped cream." Those shows, to me, I get that they're popular and they're all making money from them.

My problem with those kinds of competitions is that they don't really reflect or teach what it's like to be a chef in the real world, with those ridiculous time restraints and limited ingredients. "You can only use ingredients from a vending machine."

I think that why you don't see real chefs as competitors; you see them perhaps as judges. Even Ted Allen, the host of "Chopped," I've known him from when he was a critic here in Chicago. I always respected his views because he analyzed the food and dining experience in a really respectful way. He was top notch. And yes, you look at some of the competitors like Rick Bayless, Graham Elliot Bowles, or anybody on "Top Chef Masters," these are super-talented restauranteurs and chefs. It's such a weird mix to me. Are they going on these shows to bolster their brand? To make their restaurants busier? Probably so, right? Honestly, as an entrepreneur, you can't blame them for that. I put more blame on the content and what the producers hope that they will say. You've got your Gordon Ramsey for that.

Sometimes, I look at these shows and I just laugh. The worst show — I can't remember the name of it [I believe he's referring to "Restaurant: Impossible"] — is with the crew-cut guy, I think he's an ex-Marine. He's got giant biceps and he's barking at everyone, "You guys suck. We're going to reinvent your restaurant." Why is this a show? Because in reality, we've all known how to open a restaurant. When we did Next and Aviary, we came into a space that we knew we were going to totally renovate, but we did it in a more romantic fashion where we got six to eight key people who understood what we wanted to accomplish. It was a conversation. It wasn't "I'm going to take a sledgehammer and blow out this wall!" Come on. I get that it makes for good TV and it pays everybody, but it would be nice if the dining and viewing public would be less interested in drama and more interested in true creativity.

Photo by Lara KastnerIn all areas of life, sure.

Yes. Well put.

How much of your success to you attribute to being in Chicago? Do you think the reception to the way Alinea and Next do things would have been different in another city?

I don't think it would have been possible, frankly. You know what? It was pure luck. There was a point at the French Laundry where I went to Thomas [Keller, chef and owner] and I said, "It's time for me to leave the nest. I love it here; this place is incredible, special, but now I'm starting to see things that I want to create under my umbrella, not your umbrella." And he looked at me and went, "I think you're ready." So it was like he gave me permission to go, just like your parents kicking you out of the house when you're going to college.

So I did a big search. I looked at LA, San Francisco, New York City, Chicago, Miami, Boston. What I was looking for was this very clear idea of the type of cuisine I wanted to create. But more important than that was I didn't have any money. At the time, I was making $38,000 a year; I was 26 years old, right? So I had nothing saved up, and I knew that I was going to have to find someone to invest in me or a current owner that was in a position looking for chef that would give that chef carte blanche. And in New York, it's way too risky; nobody's going to do that. Same in San Francisco and LA. But I connected with Henry [Adaniya, owner] at Trio [now closed] in the suburbs of Chicago, and ultimately I did food for him, he did tastings. We talked for hours, and at the end of the day he said, "I want to support your vision. I want you to realize your goals. It's a huge risk for me, but I'm willing to take it."

I packed up all my stuff from Napa and moved to Trio to start doing the food that I felt very passionate about. It was different than Thomas Keller food, different than anything else out there. The local media latched onto it, really responsive, and was calling it the next great thing in Chicago. I met Nick [Kokonas, Achatz's partner at Alinea], who had become a regular at Trio. And at one point he asked, "Do you want to take this amazing food and put it in an applicable space?" We were in Evanston, home of Northwestern University, and I love Evanston, but there was no foot traffic. We were in an old hotel, and Nick was like, "Man, if we put this in Lincoln Park or the Gold Coast, we woud have so many more people and doing so much better." So we partnered together and opened Alinea in Lincoln Park.

Alinea was my first restaurant, and my personal goal was to make it the best restaurant in the United States. And then I had aspirations to make it the best restaurant in the world. So when we took over that space, we built is as such. The kitchen was realistically larger than it needed to be; the dining rooms were larger than they needed to be, the tables were bigger. Everything was a little bit exaggerated because at the time, I thought we needed to exceed everybody and do this without personality injected into it but make it like everything we'd ever dreamed of. And to a certain degree, it worked.

One of the things that Spinning Plates teaches us about a community rallying around some of these smaller places. Do you have a sense of a restauranteur community in Chicago, or are the players to big to talk to each other at this point?

Similarly to what happens in New York City and San Francisco... like last night, for example, we had our final premiere afterparty [at Next], and a good majority of the room were chefs and restauranteurs, people that we consider friends. You had Giuseppe Tentori from GT Fish & Oyster; Curtis Duffy from the recently opened Grace; just a ton of local chefs there to support what we're doing. It's really sometimes difficult to assess. At the same time, there are a lot of chefs that just don't get along in these communities, that we would never invite or would never expect to come. And I think it's the same way in a lot of industries, whether it's because of ego or competition, whatever it is.

The scenes in the film where you're in the kitchen with your kids, I couldn't help but wonder if they watch the film Ratatouille differently than other kids.

[laughs] They've definitely watched it a couple of times. You know, the oldest one, Kaden, he was born in Napa, so he has a very special connection to Thomas, and he understands that. Once a year, they go to Napa. The younger one is named after Thomas — his first name is Keller. They get it and they understand the importance of mentoring and cooking. I really think it is an important part of who they are and understanding who I am. They like cooking, but they're boys.

Tonight, for instance, they're on their way home from school, and we're going to give them a couple of options. One of them has a 102° fever, so he skipped school today. I talked to him earlier and asked, "What do you want to eat?" And he said, "Maybe just chicken soup." And I'm like, "Cool." In this house, we really run the gamut. There are nights when we order from Homemade Pizza Company or Potbelly, or we order Lillie's Q and we go pick up their barbeque, and those are some of our favorites. But the other things that we do is have a really crappy, halfway melted Weber grill out on our patio, and we fill it with hardwood, light it up and grill some really nice rib-eye steaks.

Tonight, I said, "How about this? We light the fireplace and we put a cast-iron pot on there with a whole chicken, and we make you chicken soup in the fireplace. And when you involve fire with a young boy, everything is good in the world [laughs]. Luckily, that is what's happening tonight. We're going to throw a big crock in the fireplace and throw a chicken in there with some carrots, celery, onions, let it bubble away; he'll be happy. We'll put on a movie, we'll make them do their homework, we'll make them do their obligatory 20 minutes of piano. It'll be good.

In the documentary, when you're showing us some of that incredible equipment that you use in the kitchen, there's a glimmer in your eye, like when science fiction become reality. Tell me about the importance of those more unusual elements to the restaurant.

Achatz preparing dessert tableside at Alinea; photo by John JohAt any moment when I walk through the Alinea or Next kitchens, I feel like a kid in a candy store. As a cook, you realize that you have pretty much every tool that you could possibly dream of to help you achieve a goal. You can be a videographer, and now they have that crazy phantom camera that can do all that bananas stuff — and we've used that a couple of times — but they also love going back to antiquated cameras. We have thermal circulators and stuff like that, but we always view them as tools.

I always say to people, in the '70s my old man used to hang drywall for a living. He would put the nails behind his ear, and he would pull one out and with one stroke of the hammer, it would push through that sheetrock into a 2x4. And now, they use a nail gun, but they're still hanging drywall. We can talk about that with regards to music and film. I remember eight-tracks and CDs; now we all have our iPhones and iTouches.

For whatever reason, people don't connect the dots between technology and other mediums and food. And I don't know why that is. Maybe because food becomes so nostalgic. For example, my mom bakes me the same birthday cake that she baked me when I was eight years old. Nothing has changed, and I don't want anything to change because it's delicious. But when I look at the birthday cake — and I literally said this to her a year and a half ago — I'm like, "Mom, you could set aside the chocolate portion, let it cool down, cut it into cubes; then instead of whipping the buttermilk frosting, you could put it in an iSi Foamer...," and she looked at me like I had four heads [laughs]. But it's the same thing.

With the restaurants, I feel it's the same thing. Alinea is always going to push and strive for that Michelin three-star level and still try to be the best in the world. We're coming up with crazily creative foods, like floating apple balloons filled with helium that you suck out and you talk like Mickey Mouse. That's the other thing that people misperceive, perhaps from the movie, is that they think when they put these three restaurants side by side, and they look at Alinea, they think, "Oh, they're so pretentious." We just want to make people laugh. We're making people suck helium out of balloons like you did at a carnival or circus when you were eight years old; that shit's funny! And you're in a dining room, and be okay with that. We're trying to bridge all those gaps, and I think it's working.

Do you have any favorite food-themed movies — documentaries or otherwise?

One in particular that I find very evocative, and we've toyed with it a bit. It's not really a food documentary; it's... you're going to have to help me here [with the title]. It's the Peter Greenaway film...

Oh, The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover?

Yes! The way he deals with color. Culinary is weaved through the film. Christ, they end up cooking the dude at the end, right? But the way they deal with the color, to me, was very inspiring. As a creative team, there were about six of us that sat down a year ago to figure out how we could transform maybe a room or a course or something, where it's red velvet and roasted meats. I mean, we're not going to cook a person, obviously. But the whole idea of colors — reds and blacks — how could that contribute or contrast to a meal at Alinea. I feel like there's a lot of potential there that we might want to play with. We look at all that stuff.

I love the fact that you felt like you had to inform me that you weren't going to cook human flesh.

[laughs] Not going there!

Do you have time for any other leisure-time passion outside of food?

Obviously, I have my boys. We're going to play the piano, make sure they do their homework. I make them read for a half hour, whatever they want to read. We have a ping-pong table, which they typically love to play. Usually we play Yahtzee or Jenga. I want them to be into it. But I also feel that there's that human element, especially because I'm divorced and I only see them three days a week, so I want them to feel that they can wrestle with their father. We build forts, play guns, but they're going to help me cook dinner. I don't trust them with real knives yet, but I bought them Zyliss plastic serrated knives that cut really well, but even if they jam it into their hand, they're not going to get cut. We play that game too.

I confess, I've never been to one of your restaurants before, and I will make it happen. But in all likelihood, before that, there's going to be a road trip to that little town in Iowa to eat some fried chicken.

Maybe we can go together, because me and a bunch of my team are going up there. After meeting them and finding out that they were such cool people, we were just like, "Man, we have to go." So we can rent a bus and shoot over there; that would be cool.

I won't hold you to it, but that would be incredible. Grant, thank you so much for talking. And have fun with the kids.

Awesome. Great talking to you. You know what? This was a great interview. Thanks.

~*~

Spinning Plates screens at the Landmark Century Centre Cinema, 2828 N. Clark St., through Thursday, Nov. 7. Read Gapers Block film critic Steve Prokopy's review of the film in A/C.