| « Senator Kirk Releases a New Recovery Video | The Battle for an Elected School Board » |

Chicago Wed Aug 15 2012

Religious Freedom Vs. Aldermanic Privilege? Or the Subversion of Historic Preservation? The Battle Over St. Sylvester's Rectory

Photo by AJ LaTrace

On Monday, Aug. 6, nearly 200 members and supporters of St. Sylvester Parish marched from their church at 2157 N. Humboldt Blvd. to 35th Ward Alderman Rey Colón's office at 2710 N. Sawyer Ave. Holding signs and singing songs of solidarity in English and Spanish, the group picketed for nearly an hour in front of Colón's office, while the alderman held his monthly ward night for constituents.

Claiming their religious freedom had been violated, the protesters rallied over Colón's alleged refusal to help the parish find a way to remove the official Chicago Landmark status of their rectory. While the rectory was designated as a landmark as part of the Logan Square Boulevards District established in 2005, the parish said it never wanted the building in the district, can't afford to maintain it, and would rather tear it down, but can't due to the building's legal protection as a landmark. Furthermore, the parish alleged that the alderman had purposely left his house out of the district, and should use his power as alderman to help St. Sylvester do the same. Meanwhile, a dozen counter-protesters from a group called Logan Square Preservation stood in front of the alderman's office with their own signs and slogans, calling for the preservation of the St. Sylvester rectory's landmark status - and the building itself -- at all costs.

To understand what exactly took place, and why a building typically used to house clergy members even became a historic Chicago landmark, it's necessary to go all the way back to the early history of Logan Square.

In 1837, the newly incorporated city of Chicago adopted the motto "Urbs in Horto," or "city in a garden." Twelve years later, real estate developer John S. Wright took this idea and proposed a system of boulevards to completely surround the rapidly expanding city. The idea took root over the next 20 years, and by 1870, the West Park District (created a year prior by the state of Illinois) began the planning, design and construction of a unified system of boulevards and parks along the western edge of Chicago, including present-day Garfield Park, Humboldt Park, Palmer Square and Logan Square.

In 1884, the Archdiocese of Chicago formed St. Sylvester Parish in what was then Jefferson Township, part of which later became the Logan Square neighborhood. In 1889, the city annexed the Township as scores of well-to-do German and Scandinavian immigrants moved into the area and built graystone houses, mansions, and two- and three-flats alongside the new boulevard system. By 1896, the parish moved from its original location at California and Shakespeare avenues to its current location across Humboldt Boulevard from the eastern edge of Palmer Square. The current church was built by 1907, and the rectory soon followed in 1911.

St. Sylvester Church and Rectory. Photo by Andrew Huff

After flourishing as a commercial and population center for the first three decades of the 20th century, Logan Square reached its economic and population peak in 1930. But starting with the Great Depression and continuing with emigration of well-to-do families to the Chicago suburbs after World War II, the neighborhood's economy dwindled, and the boulevards and surrounding buildings fell into decline.

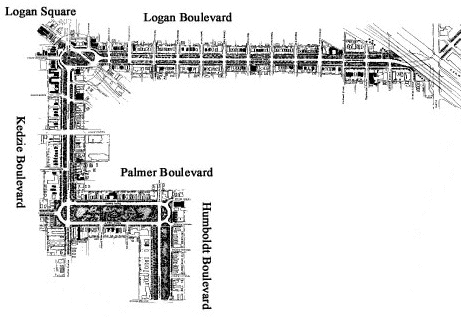

In 1968, a city ordinance created the Commission on Chicago Landmarks in order to recommend buildings, sites, objects and districts to the City Council for legally-protected preservation. Later, in 1980, a group of neighborhood residents formed Logan Square Preservation, an organization dedicated to restoring, preserving, and promoting the neighborhood history, boulevard system, and the original architecture of the buildings surrounding it. By 1985, the group convinced the U.S. Department of the Interior to designate a 2.5 mile section of the boulevard system within the Logan Square and Humboldt Park neighborhoods as a nationally registered landmark called the "Logan Square Boulevards Historic District." This designated district consists of Humboldt Boulevard from North Avenue to Palmer Square, Kedzie Boulevard between Palmer and Logan Square, and Logan Boulevard east to the Kennedy Expressway.

While National Registry designation offered tax and restoration incentives to homeowners along the boulevards, it didn't guarantee the actual preservation of the historic buildings. So in 2002, Logan Square Preservation met with the at-the-time 35th Ward Alderman Vilma Colom and the Landmarks Commission to propose the idea of designating the area under the National Registry as a city landmark district. Subsequent community meetings were held to educate building owners about the landmark process and gather opinions from the community.

And this is where the versions of the history begin to diverge.

Logan Square Preservation's website says the following about the March 2004 referendum put up by newly-elected Alderman Rey Colón: "Our Alderman agreed to place a referendum on the general ballot asking whether or not citizens felt the boulevards should be preserved. An overwhelming 89% agreed, and that was the stimulus needed to pursue the idea with vigor. "

The literature passed out by St. Sylvester representatives at the Aug. 6 protest told a slightly different story. According to figures they cited, the percentage of voters in favor of the March 2004 referendum approving the idea of creating a landmarked district was actually 87.35%. Of the 23,024 voters registered at the time, only 6,377 voted in the election, and only 3,852 voted in favor of the district. 558 voted no, and 1,967 didn't vote. By their logic, only 17% of registered voters voted in favor of the district, in opposition to the narrative of overwhelming neighborhood support. In response, Ward Miller, the vice president of Logan Square Preservation, said he didn't think "the priest should challenge an election count and vote, and determine eight years later that somehow there's something wrong." In either case, Alderman Colón used the referendum result to support the creation of two landmark districts: one based on the six-corner intersection of Diversey, Kimball and Milwaukee avenues, and the other based on the 1985 Logan Square Boulevards Historic District boundaries.

Currently, 311 individual landmarks and 53 landmark districts have been designated as Chicago Landmarks, nearing 10,000 properties in total. There's an eight-step process [.pdf] to designating a landmark. First, commission staff members research the historic and architectural significance of a proposed building or district, and submit a report to the commissioners, who then vote whether to start the consideration process for a proposed designation. After a vote in favor, the Department of Housing and Economic Development releases a statement about how "the proposed landmark designation affects neighborhood plans and policies." The commission contacts each affected building owner and requests owner consent. With the exception of "houses of worship," the consent is advisory. Public meetings are then held to gather information for the commission to use to determine the proposed landmark designation. After a final review, the commission votes to whether to recommend the proposed designation to the City Council, which is then voted on by the City Council Committee on Zoning, Landmarks, and Building Standards. If the Zoning committee votes in favor, the designation vote is brought to the full Council and the Chicago Landmark is then designated by a City Council legislative act. In the case of a landmark district, only buildings that are considered "orange-rated" and contributing to the historic significance of the district are the ones that become designated landmarks. Beyond owning a protected piece of Chicago history, the perks of a building with landmark status include income tax credits and deductions, building and zoning code exceptions and waived fees for City Building Permits.

The Logan Square Boulevards District. Image via Logan Square Preservation

The report that the commission generated for the Logan Square Boulevards District can be found here [PDF]. It includes the historical significance of the boulevards and neighborhood, the criteria used to determine the proposed district's eligibility, the architectural period being preserved (anything built between 1880-1920), a map, and a list of all the buildings in the district. According to the Logan Square Preservation website's account, "The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, Department of Planning sent notices to building owners along the proposed district, and many public meetings were held. Although initially there was some opposition, it soon waned as meetings progressed, and at the final two public hearings there was no opposition voiced. The Commission on Chicago Landmarks unanimously approved the proposal on October 27, 2005 and on November 1, 2005 the Chicago City Council designated the 'Logan Square Boulevards District' as an official city landmark district."

According to literature handed out by Logan Square Preservation at the Aug. 6 protest, the rectory is historically significant because it was built by prolific architectural firm Worthmann & Steinbach. Active between 1903 and 1928, the firm built a number of churches and residential buildings that are currently landmarked by the city today. Curiously, the rectory is not listed on the Chicago Historic Resources Survey's online database of historically significant buildings. And in the Logan Square Boulevards District Preliminary Landmark recommendation, the rectory is not listed as a Worthmann & Steinbach building, whereas several other buildings in the district are. At the same time, the rectory is one of many buildings listed in the recommendation as "contributing" to the historic nature of the Logan Square Boulevards District.

According to literature handed out by Logan Square Preservation at the Aug. 6 protest, the rectory is historically significant because it was built by prolific architectural firm Worthmann & Steinbach. Active between 1903 and 1928, the firm built a number of churches and residential buildings that are currently landmarked by the city today. Curiously, the rectory is not listed on the Chicago Historic Resources Survey's online database of historically significant buildings. And in the Logan Square Boulevards District Preliminary Landmark recommendation, the rectory is not listed as a Worthmann & Steinbach building, whereas several other buildings in the district are. At the same time, the rectory is one of many buildings listed in the recommendation as "contributing" to the historic nature of the Logan Square Boulevards District.

When asked, Miller and Alderman Colón both remembered seeing a complaint letter from the Chicago Archdiocese, and Miller recalled a representative of the church showing up to one of the public hearings, but neither recalled loud, vocal opposition seven years ago over the rectory's landmark designation like the recent protest. According to Ward Miller, there was plenty of opportunity to speak out about the proposed district, adding, "It seemed to be a fair, open process."

The St. Sylvester side of the story, once again, is a little different. As mentioned before, there's a religious exemption to the Chicago Landmarks Ordinance [.pdf]. Section 2-120-660 states "No building that is owned by a religious organization and is used primarily as a place for the conduct of religious ceremonies shall be designated as a historical landmark without the consent of its owner."

The Preliminary Landmark recommendation lists 10 churches that did not consent to being part of the District, including St. Sylvester Church. In addition, the Catholic Archdiocese indicated its non-consent to including the rectory in the proposed district on March 3, 2005. At a July 19, 2005 public hearing on the proposed district, representatives of the Archdiocese objected to the landmark designation of all of the buildings it owned under the First Amendment, and requested until July 30 to submit a written testimony to the Landmarks Commission, outlining their position.

On July 26, Jimmy M. Lago, the chancellor of the Archdiocese of Chicago, swore an affidavit alleging that "All the buildings at St. Sylvester are used to further the mission of organized evangelization, including its Church, rectory, and school." The Archdiocese also sent a letter to the commission (with Alderman Colón cc'ed), further challenging the inclusion of the rectory on the grounds of religious freedom, and disputing the restrictive language used in the "Building Owned by a Religious Organization" section of the Chicago Landmarks Ordinance to define the boundaries of religious practice. In particular, the Archdiocese claimed the rectory was used for a variety of religious ceremonies, including prayer groups, the Liturgy of the Hours, and up until 1970, weddings held between Catholics and non-Catholics, and should thus have been exempt from landmark status to begin with.

When asked if he felt there was any merit to the idea that the rectory could be exempt under the language of the Chicago Landmarks Ordinance, Colón dismissed the argument. In an email, he wrote, "The church is stretching the truth by claiming the Rectory as [a] place for conducting religious ceremonies. The Rectory is a residence owned by the church. They believe as a religious organization that they should be exempted from the law." He then quoted Matthew 22:21, which states, "Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar's, and unto God the things that are God's." He pointed out that churches and non-profits generally complained about being included in landmark districts because the extra maintenance costs associated with things like having the correct windows. "I think what people don't understand," he explained, "is as long as you keep the façade intact, you can do whatever you want on the inside. It's just really about the façade more than anything else, and things that are visual from the street."

However, Rev. Stein noted, "The original 1968 ordinance simply stated that houses of worship should be exempt, and in light of how many activities took place in the rectory as an extension of the church building proper, I think it should likewise be exempt. Otherwise, the government is deciding what does or does not qualify, or how much does or does not qualify as worship."

Beyond the legal classification of their rectory, St. Sylvester's recent protest also questioned Colón's own actions during the creation of the district.

The Historic District in the National Registry starts at North Avenue and Humboldt Boulevard, and goes north to Palmer Square. However, the boundaries of the Logan Square Boulevard District start at Cortland Avenue -- roughly three blocks north of the Historic District boundary and two blocks north of Alderman Colón's own house along Humboldt. To explain why the border of the Landmark District was at Cortland instead of North, St. Sylvester's press materials included two pieces of evidence that seemed to imply that the alderman had zoning power he simply chose to abuse.

The first was a July 24, 2010 article in the Chicago Tribune, detailing the circumstances in which Alderman Colón bought his house with a no-money-down loan from a property owner and approved a zoning change in the surrounding vacant property on behalf of a housing agency that bought the rest of the land. He then had his property taxes paid by the housing agency, and received political contributions from both the owner and the agency. Colón explained to me that the situation was messy because both the house and surrounding property were both under the same PIN number, and the agency paying part of his property taxes made sense while they went through the process of subdividing the property. He said, "There was this whole forensic auditing done with my finances," and claimed that the article made an insinuation without any proof.

The other assertion was a quote from the minutes of the July 19, 2005 hearing on the proposed Logan Square Boulevards District by Patricia Lauber, who alleged that she heard "a very powerful developer owns properties on the east side of Humboldt, a block and a half south of the termination of the historic proposed landmark district and he's reassured Alderman Colón that he will build something historic."

As Colón wrote to me via email, "The 26th Ward alderman at the time had portions of Kedzie and Humboldt Boulevards. He agreed to Kedzie, but did not sign off on the west-side of Humboldt from Cortland to North Avenue to avoid having Bikerdike [sic] Redevelopment Corporation's (a non-profit developer and property management organization) buildings in the district or subject to Landmark approval on their permits." Geographically, this checks out, as south of Cortland, Humboldt is split between the 35th Ward on the east side and the 26th Ward on the west side. Colón also mentioned, "Rather than have this odd shaped district, it was recommended at the time that we cut it off on Cortland." The former 26th Ward Alderman in question, Billy Ocasio, is currently the Director of Community Affairs for the Illinois Housing Development Authority. He could not be reached for comment.

The testimony of another woman at the July 19, 2005 public hearing, Erika DeRoin, supports the notion that the establishment of the Cortland border was Ocasio's doing, rather than Colón's. Complaining that there was no uniform process for aldermen to follow to determine how to establish a landmark, she said, "The Logan Boulevard historic district was placed on the National Register in 1985, and my husband and I helped to create that, and it includes Humboldt Boulevard up to North Avenue. Alderman Ocasio wishes the Chicago Landmark District on Humboldt Boulevard to stop at Cortland Street." But in a point later echoed by St. Sylvester, she added, "If Alderman Ocasio can change part of the current National Historic District to satisfy his political constituents, why has Alderman Colón refused to?"

Colón acknowledged that his home is orange-rated, and in the event that the Logan Square Boulevards District was extended to North Avenue, his house would be unable to be torn down. He wrote, "I thought I might be able to have the entire remaining 2 blocks of Humboldt included in the ward remap in the future to complete the historic district and make it compatible with the National Registry of 1985. As it turned out, not even my house will be in the future 35th Ward. Someone else will have to finish this work."

During my initial interview with Alderman Colón after the protest, I brought up the some of the arguments made by St. Sylvester. After responding to a few points, he said, "It's really kind of a smear campaign, and that's all being done by Fr. Stein, who, quite frankly, is just not totally honest when it came to giving me the circumstances around rectory."

In a follow-up interview at St. Sylvester Church, Rev. Stein explained the history of his own understanding of St. Sylvester's rectory problem. At the end of June 2006, Fr. Mike Herman -- who was at St. Sylvester during the 2005 landmark campaign -- left St. Sylvester Parish, and the church had no pastor for a year. Rev. Paul Stein came to St. Sylvester in July 1, 2007, and said he immediately saw problems with the upkeep of all the parish's buildings and the amount of money they had.

Between spring and winter of 2008, Rev. Stein and members of the parish worked on an official "Master Plan" to determine what could be done with the buildings. Eventually, the functions taking place in the rectory building were moved to the church's convent building (which had previously been loaned to Catholic Charities) and an old hall behind the church was demolished to build a new parking lot. According to Rev. Stein, the problem with what to do about the rectory kept getting put off until Holy Week in April 2011, when a pipe burst in a wall at the rectory, burning out circuits and spreading mold. This finally prompted the parish to look for a permanent solution.

St. Sylvester received quotes to repair the rectory from two different construction companies, one on March 19, 2009, and another on June 21, 2011. The latter quote estimated a cost of around $1.4 million to renovate the rectory, with individual costs ranging from masonry and plaster to plumbing and electrical work, along with a cost for a building demolition. Meanwhile, renovations to the church itself were quoted at an additional $1 million.

Faced with the costs and a deteriorating rectory, Rev. Stein said this is when he began to approach Alderman Colón and members of the Landmark Commission about the issue, and applied for a permit to demolish the building in July 21, 2011. He claimed he was not initially aware of the previous objection to the rectory's landmark designation until he started asking the alderman for assistance and kept getting rebuffed, noting, "I thought it was a done deal, I didn't know the history behind it." Stein claimed the alderman finally sent him an email in December or January saying that he couldn't support the parish on this. At the same time, Stein received word that he would be transferred to the position of Rector-President at Loyola University's St. Joseph Seminary, and that the estimated earnings for the upcoming St. Sylvester capital fundraising drive would not even raise enough to make repairs to either the church or the rectory, much less both. Combined with finding out about the history of the previous objection by the city, he decided to take the fight over the rectory public.

In March of this year, Rev. Stein asked the St. Sylvester congregation to call and email Alderman Colón to ask him to help the parish remove the landmark status from the rectory. One parishioner, Larry McIntosh, received a frank email reply back from the alderman on March 13 that stated, "I don't support the demolition of the Rectory and neither does the Chicago Landmarks Commission. That being said, my position would change if St. Sylvester's can generate overwhelming community support for it. I am confident that there is very little support to remove the Rectory from the historic district, but if I am wrong, it is St. Sylvester's responsibility to find support for this, not mine."

From there, the church decided to launch a "Save St. Sylvester" campaign to prove that there would be community support for tearing down the rectory. They went around to nearby Catholic parishes to explain the situation, and as Rev. Stein pointed out, "If you add up all the Catholics in the 35th Ward, that's a lot of people." From there, St. Sylvester reached out to churches from other denominations and posted flyers throughout the surrounding neighborhood, garnering further support for what became the protest on Aug. 6 to pressure Alderman Colón into overturning the rectory's landmark designation.

As a spokesperson for the Commission on Chicago Landmarks confirmed to me, there is no formal process to de-designate a landmark under the current wording of the Chicago Landmarks Ordinance. To get around this, St. Sylvester has publicly called for Alderman Colón to sponsor what they call a "variance ordinance" to undo the landmark status of the rectory. A "variance" in this case is generally defined as a special rule or exemption to pre-existing zoning law. Rev. Stein told me this was suggested by "outside political counsel," but would not specify who that was or exactly when the idea was brought up.

In a prior email interview response, he wrote, "Alderman Colón was the sponsor of the 2005 ordinance that created the Boulevard district in the first place. He can sponsor a variance ordinance to the original to remove us from the district. The City Council would then vote on it. Because it is still his ward, and aldermen abide by the unspoken rule not to directly interfere in another alderman's ward, he has great power to make the change."

Incidentally, Colón is a member of the City Council Committee on Zoning, Landmarks, and Building Standards. However, he disputed the notion that he could simply pass a variance ordinance. "First of all it has never been done," he wrote. "Properties don't get annexed out of historic districts. It would require me introducing an ordinance which would go before the Landmark Commission where it would be voted down. Even if it did get passed, and went before the full City Council for a contentious vote, I don't want to be in the middle of a fight I don't believe in. I believe removing the Rectory from the historic district is a sin."

Miller also voiced fears that the removal of the rectory's landmark status could set a precedent and undo historic preservation efforts all across Chicago. However, the rectory issue isn't the only seeming threat to the Chicago Landmarks Ordinance. Two property owners filed a lawsuit against the city over what they alleged to be unconstitutionally vague standards in determining what buildings get landmark protection, and in 2009, the Illinois Appellate Court ruled the that the law was unconstitutionally vague. In May of this year, Circuit Court Judge Sophia Hall ruled that the law was constitutional, but there are already plans to appeal to the state appellate court. In reporting Judge Hall's verdict, Chicago Tribune critic Blair Kamin wrote, "Hall's decision marks the latest twist in the slow-moving case, which has drawn national attention because other cities, including New York and Boston, use language like Chicago's in outlining the legal standards for historic preservation."

When I asked if the Archdiocese had ever considered a similar lawsuit, given their legal objection to the Chicago Landmarks Ordinance language in 2005, Rev. Stein acknowledged that the topic has been discussed, but that they would rather find a "workable solution."

When I asked if the Archdiocese had ever considered a similar lawsuit, given their legal objection to the Chicago Landmarks Ordinance language in 2005, Rev. Stein acknowledged that the topic has been discussed, but that they would rather find a "workable solution."

But until the courts conclusively rule either way, the language of the ordinance still stands. Ward Miller felt that at end of the day, the rectory has a highly desirable structure that could be used in a variety of beneficial ways to the community, adding, "Why shouldn't we all abide by the laws and ordinances of the city of Chicago? We all have to play fair on this."

Rev. Stein dissented, stating in an email, "It puzzles me that the alderman and the preservationist cannot see the bigger picture. Fighting over one building without sight of the others is losing sight of the forest through the trees. Of course, none of them attend St. Sylvester and none of them have donated to the preservation of the campus. Perhaps if they had their own money invested in the community, they might see things differently."

Alderman Colón, as it turns out, has a long history with St. Sylvester. He wrote, "I went there for Catechism classes and my First Holy Communion. I've contributed to fundraisers and gave $500 toward their scoreboard for their youth sports program. I also had a controversial ordinance passed that allows them and all boulevard churches to park free and legally during religious functions." In fact, Rev. Stein wrote a letter to the Tribune thanking Colón for his support of this parking ordinance.

If there's anything all sides can agree on, it's that they want a resolution as soon as possible. Logan Square Preservation wants to find a way to fund the preservation of the rectory, regardless of its future use. St. Sylvester Church wants to be rid of the financial burden of the rectory upkeep, but still keep the property. And Alderman Colón wants to stay on the same side as Logan Square Preservation and avoid being pressured into making an unprecedented City Council maneuver that could have major ramifications for the future of historic preservation efforts. However, Stein says the fight isn't necessarily over. He said that if a solution isn't reached, "Most likely, we will plan more protests."

In an interesting twist, this issue may soon be out of Alderman Colón's hands. In the new ward map taking effect in November, Alderman Colón's new 35th Ward boundaries don't include any part of the Logan Square Boulevard District he helped create, with the exception of the northwest corner of Logan Square containing Norwegian Lutheran Memorial Church. The majority of the district will fall within Scott Waguespack's new 32nd Ward boundaries. Part of Kedzie and a smaller chunk of the western half of Humboldt in the National Registry will remain in Roberto Maldonado's 26th Ward. But the contested Cortland boundary, Alderman Colón's own house, and St. Sylvester's rectory itself will go to Joe Moreno's new 1st Ward... an ironic turn of events, given the widespread criticism and allegations of oppressing religious freedom Moreno has received over using aldermanic privilege to block the construction of a Chick-Fil-A in Logan Square.

When asked if St. Sylvester would take the fight to Alderman Moreno, Rev. Stein said he'd rather resolve the issue now, and not take it to the new alderman. However, he added, "We don't want this to become his problem, but it will be his problem if it's not dealt with."

Roland S / August 15, 2012 6:02 PM

Seems like the church should borrow money to renovate the rectory as apartments, then pay back the loan with the rental income. Once the loan is paid off, the church can use the building as it sees fit. Everybody wins.