| « Suggestions for 2009 Selections | Chicago Publishers Gallery » |

Feature Wed Oct 15 2008

An Interview with Irvine Welsh, Part 1

by Alissa Strother

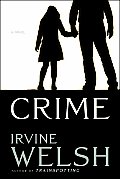

Crime, the latest novel by Scottish writer Irvine Welsh (Trainspotting, Filth), follows Detective Inspector Ray Lennox from Edinburgh to Miami as he attempts to recover from a stress- and drug-induced mental breakdown and salvage what is left of the struggling relationship with his fiancée. Instead of a relaxing holiday, Ray finds himself assuming the role of guardian and defender for a frightened ten-year-old girl in the middle of a dire situation. Never one to shy away from difficult subject matter, Welsh explores everything from abuse to organized crime to innocence, guilt, secrets, blame, prejudice, truth, deceit, consequence, corruption, and ultimately, redemption in his most recent work.

Crime, the latest novel by Scottish writer Irvine Welsh (Trainspotting, Filth), follows Detective Inspector Ray Lennox from Edinburgh to Miami as he attempts to recover from a stress- and drug-induced mental breakdown and salvage what is left of the struggling relationship with his fiancée. Instead of a relaxing holiday, Ray finds himself assuming the role of guardian and defender for a frightened ten-year-old girl in the middle of a dire situation. Never one to shy away from difficult subject matter, Welsh explores everything from abuse to organized crime to innocence, guilt, secrets, blame, prejudice, truth, deceit, consequence, corruption, and ultimately, redemption in his most recent work.

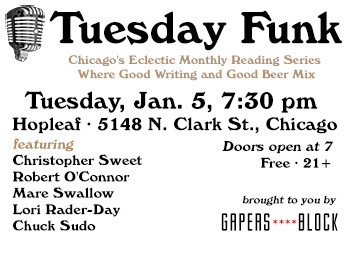

Fresh off of the previous night's Read Against Recession event at The Metro, I talked book tours, writing, teaching and, of course, Chicago, with one of the most well-rounded men in the literary world today.

Gapers Block: What did you think about Read Against Recession last night?

Irvine Welsh: I thought it was great. Stephanie [Kuehnert] and Bill [Hillmann] were very good. When I go to places and do book tours, I don't really like doing traditional bookshops. It's nice to walk people through something instead of just standing up in a bookstore. Sometimes you have to do the big bookstores as well and some of them are really good, like the Barnes & Noble in Union Square in New York, for example, but I like some of the bigger independent bookstores, like Book Soup in LA. They are really good to work with. Powell's in Portland is great for events. And Books & Books in Miami - I have a reading at Books & Books and a party at White Room after. PowerHouse is this bookstore that can also manufacture and publish a book, so it's a huge, great space. Readings are quite boring, really. You can't really perform and it's just nice for you to put a face or a voice to a book. Stephanie and Bill both put a lot into it.

GB: Stephanie was your student a few years ago, right?

IW: Yeah, she was one of the students when I was teaching at Columbia. There were a lot of really good, talented writers, but I think that the X-factor that she had was that total dedication. She just really wanted to do it and I think that's the sort of thing that was always very impressive, that she was 100% into it. I'm not surprised that it's been successful, her book, and I think she'll continue to be successful. She's got a new one coming out next year as well so she's kind of up and running.

GB: How did the teaching gig at Columbia College come about in the first place?

IW: I came to Columbia for Story Week and after that they asked me if I wanted to come back and do a year's teaching. I vibed with Chicago. I liked the place and I'd become friends with a lot of people, so it seemed like a nice thing to do.

GB: And now you have a pretty substantial connection with the city.

IW: Yeah, my wife's from Chicago. I met her in a bar one night and we just kind of clicked. It was a snobby kind of hotel bar downtown; it was this Irish kind of theme pub that was in the basement one of these very soulless hotels on Michigan Avenue. I was just out for a drink with some pals and she was out for the night. Because of our connection it means that I'm able to be here a lot of the time and we've got an apartment here. Most of her family is out of state, but a lot of her pals are here so I like to get over a bit in the summer.

GB: You've been incorporating more American characters into your short stories lately and obviously in Crime there are quite a few. Do you find it a challenge to write the American characters?

IW: Not really, I don't really think of it in that way. I think it's because I've been spending so much time over here. I don't even realize that I'm doing it, but it is interesting. I don't even really want to consciously do it. I kind of want to keep writing about where I come from in Scotland and the UK and all of that, but it's also good to get out of where you come from as well. You get into a comfort zone, writing about the same place, so it's probably a good thing for me to do, but I'm not sure quite how far I want to take it.

GB: You mean as far as creating a novel with an entirely American cast?

IW: It's more a sort of sense of place that's relevant rather than people and characters. It's like if you're driving down Western Avenue and you see all of these car dealerships and you start to get something in your mind. That kind of setting can spark something and it would have to be an American novel. You don't get the geography like that in the UK. You don't really get these kinds of places in the same way, you know, they need to be located in the same type of environment.

GB: Do you think you will ever base a novel in Chicago?

IW: Yeah, it's strange because I think that I could, but it wouldn't be the same as if you get a Chicago writer like Stephanie or Bill or Don [De Grazia]. It wouldn't be the same. I wouldn't have the bond with the city that they have so it would be more as a backdrop to a character-based thing rather than getting into the nuts and bolts or grit of the city. I wouldn't rule it out because I think it's a great setting for a novel, though.

GB: I know you revisit characters a lot in your novels. Lennox, for example, a side character in Filth, ends up being the main character in Crime. Do you feel like you have unfinished business with them?

IW: Yeah, it's almost like a movie in a way and you're thinking, "Who can I cast in this role?" Lennox just seemed to fit the bill. I thought this guy had to be able to negotiate his way around and sense crime and sense criminals, so he had to be a cop, but he couldn't be an American cop because if he was a cop from Chicago busting up this child abuse thing in Florida he would have resources here. He would know the system and have contacts in law enforcement and be able to go into the straight bureaucracy of it all and sort it out there. So I was thinking about the guys in Filth and this guy Lennox, he's done all of these things, but you don't really know why he's a cop. He seems to be a character of secrets and I thought about secrets and the idea that sex abuse thrives on secrecy within families and within society and the church and it grew organically, really.

GB: Crime is obviously a serious novel that deals with solemn issues, but you've also called it your most uplifting novel. What makes it different from your other ones?

GB: Crime is obviously a serious novel that deals with solemn issues, but you've also called it your most uplifting novel. What makes it different from your other ones?

IW: I'm living in Ireland most of the time and you can't pick up the newspaper without there being another pedophile priest story or somebody suing the priests or the church or the Diocese for the abuse that's gone on. There was a big scandal in the 90s called the Bishop Casey Scandal and since then, everybody who's been abused, hundreds of thousands of people, have all come forward. It's opened the floodgates, so it's changed the relationship that people have with the church, and I think that was why I got interested in it. But I realized when I started to write that pedophilia isn't at all an interesting subject to write about. There's no dynamism or moral ambiguity to it. It's just basically wrong and it's evil and everybody's agreed on that. There's no ambivalence to it and it's ambivalence that makes something interesting. You can argue about violence, for example. It's destructive, but people are inherently violent in a lot of ways. Abusing drugs is always bad for people and bad for society, but the whole notion of festival is tied up with intoxication. I was writing against this whole idea that you can be like a 50-year-old pop star and it's not sort of inappropriate to have young boys sleep in your bed, but if you're a 50-year-old truck driver, it would be. I wanted to have no ambiguity about it at all and just see it as an absolute evil and have Lennox as this displaced avenging flawed angel that is trying to rescue this kid, but the kid is also rescuing him by forcing him to come to terms with what he'd been repressing. Because pedophilia was quite a boring, un-dynamic subject to write about, it couldn't be about that. It had to be about how people get over something really bad. My interest as a writer has always been about how people f*ck up and how we live in a world that can be cruel and punitive. How we compound that by making the wrong decisions has always interested me. This isn't one about how people f*ck up. It's basically about how people heal themselves so it's more positive than a lot of my books in some ways.

GB: In the research process, you talked a lot with people who had been through abuse, right? Were they pretty open to talking with you about it?

IW: That was the hardest part of it. At the start people are obviously suspicious because these books have a purpose. I think they're very suspicious of journalists, but once I convinced people that I was coming as a novelist rather than a journalist and their anonymity would be respected, [they opened up]. You can get people's stories from published case studies too, but that wasn't what it was about. I was interested in their feelings and views and emotions. It was very, very uncomfortable and I used the more uncomfortable feelings I had when hearing these stories in the book, like when the kid is telling Lennox her story. He has to listen, but he can't listen. It's killing him and I wanted to get that feeling across. When someone's telling you about these terrible things that have happened to them from a very small age you just want to be anywhere but in front of them. You kind of feel yourself withering inside listening to them but you have to listen because you've asked them and it's important to them and they want to tell you and they need to tell you. That was sort of the hardest part of the book.

GB: And you didn't do any research on the internet?

IW: I didn't want to be exposed to any pedophile sex material, just because it had nothing to do with the book and you don't want the police kicking your door down. I made a conscious decision that I was going to do no research on the 'net and I was very particular about what I needed. I needed to engage with people who had been through that, but I didn't want to engage with pedophiles or engage with child pornography. To avoid doing that, I limited the research very much to academic and case study and social work kind of stuff.

GB: How did you approach the police aspect of the novel?

IW: It's just about having contacts. People love talking about their jobs. Take them out, buy them lunch or take them for a beer and they'll talk about their job, provided they know that you're going to respect their anonymity. I'm not interested in details that might get someone into trouble. I'm more interested in generalities rather than the particulars, as a journalist would be. Names, dates and times don't interest me at all. I'm interested in feelings and emotions. Most people are game, once they realize that you're on the level as far as that's concerned and you're not about exposing them, then they feel quite free to talk about it. Police officers and social workers are no exception.

GB: Do you tend to get a different reaction from women versus men when it comes to your books?

IW: I find that a lot of the time women are more clued up about it. They sort of get more of it, because I have quite a lot of damaged male characters. A lot of guys don't recognize the damage and baggage that these characters are carrying, whereas women do more, because they think, "I've gone out with a bastard exactly like that," so they kind of see it in a sharper focus.

GB: Do you find it harder to write the female characters?

IW: Not really. I did a thing - it's not released in America yet, but I hope it will be soon - it's a film called Wedding Belles. There's one male character that's in it for about ten minutes, but there are four lead characters and they're all women. I tend to write them the same way. You write people as human beings first and then the gender specific stuff second. You see in a lot of crime novels or genre fiction where the guy's writing about a woman character and you get two pages of her putting her bra on and it's f*cking ridiculous, you know? You won't have two pages of a guy shaving or something like that or putting on a pair of boxer shorts. It's just bizarre.

GB: One of the main characters in Crime is not only female, but a child as well. Did you approach that any differently?

IW: I wanted to get somebody who in some ways is very grown up and worldly because she's been inappropriately sexualized, and is very knowing and confident on one level, but on the other hand is still a kid. That battle is going on within her. She's got these two sides to resolve. I think it's not a problem writing about any age that you've lived through. I'm writing this thing about a guy who's in his late 70s, early 80s now, so that's quite a challenge. Then again, I just try to think about how somebody like that would think about things.

GB: And you're also working on a prequel to Trainspotting. Is that already done?

IW: There's a rough draft of it from the same time as the original Trainspotting. When I wrote Trainspotting, I started out with about 300,000 words. It was huge. I took a story out and I read it at this Rebel Inc. thing and a writer called Duncan McLean, a very good Scottish writer that had been published by Random House in London, says, "Have you got any more of that? I'd like to send it to my publisher." Well, I kind of lied and said, "Yeah, I've got a whole novel." I had this thing but it wasn't a proper novel. It was kind of a mess and so I basically just chopped out the middle and wrote this kind of heist ending to finish it, because it just went on and on and on. The first part of it is all about their family background, family dynamics and how they got involved in heroin in the first place, so I discarded that part of it. The end part was superfluous so a lot of the end part I've cannibalized for different stories over the years. I've got a collection of short stories coming out next year and it's a lot of stories that have been in anthologies and journals. I guess because I didn't know what to do with it, I had forgotten all about this first part, really, until I started looking through some old files. I find as I'm getting older and a bit more reflective I'm much more interested in that cause and effect and family dynamics. I want to sit down with it next year and write it up as a proper novel. It probably needs another couple of drafts, but I don't want to lose the energy that it has. You can see it's written basically by a younger writer. It's very much like Trainspotting. I want to bring a more reflective thing to it as well, so there's going to be a difficult balance to it. That's the reason I've not gotten on with it - I've been a bit scared to have a go.

Next week, Alissa continues her interview with Welsh, talking about his life in music and his thoughts on the state of politics today.