| « Bookmarks | Begin the Madness of March with Tuesday Funk » |

Essay Tue Feb 17 2015

On Happiness (or, To Have and Have Not)

By John Rich

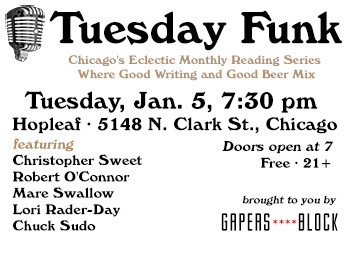

Editor's note: The following essay was read at Tuesday Funk, a montly reading series sponsored by Gapers Block, on Jan. 6, 2015.

I don't know what one means by happy

I'm happy spasmodically

If I eat a chocolate turtle, I'm happy

When the box is empty, I'm unhappy

Happiness is

Happiness is a word for amateurs.— "Happiness Is," Violent Femmes

On August 12, 2014, the American actress Lauren Bacall died of natural causes. She was a month shy of 90 years.

"Here is a test to find out whether your mission in life is complete," Bacall once said. "If you're alive, it isn't."*

Bacall, born Betty Joan Perske, became a Hollywood icon at age 19 when she starred opposite Humphrey Bogart in To Have And Have Not, a 1944 film adaptation of Ernest Hemingway's novel. It was Bacall's first movie, and the origin of her sultry chin-down-eyes-up glance, a posture adopted by necessity — it hid Bacall's nervous trembling — and then promoted as The Look.

But there's a more potent look in To Have and Have Not. At the end of the film, after the troubles have been sorted, Bacall's character, the insolent, witty, world-wise woman Marie Browning, a.k.a. Slim, says goodbye to the piano player. He asks, "Are you still happy?" And with her deep, confident voice Slim replies, "What do you think?" The band strikes up a tune and Slim walks (shimmies) towards Bogart's character, Harry Morgan (a.k.a. Steve), with whom Slim has fallen in love. As Steve takes Slim by the arm, the character Slim disappears and Bacall smiles. It's the happiest smile on film.

"I analyzed nothing then," Bacall wrote in her autobiography By Myself And Then Some. "I was much too happy — I was having the time of my life. From the start of the movie, as Bogie and I got to know each other better — as the joking got more so — as we had more fun together...our relationship strengthened on screen and involved us without our ever knowing it."

Now, Bogart might not have been good at marriage — he was on his third when he met Bacall — but he was considered to be faithful. During filming To Have And Have Not, he looked after the young actress, 25 years his junior, mentored her — and then one night he kissed her. Their chemistry was undeniable. In the DVD extras, film historian Leonard Maltin says of their on-screen effect, "It's quite possible that we are eyewitnesses to an actor or actress falling in love, and while good actors make us believe that all the time, there has to be some extra kick when it's real."

Bogart left his wife and married Bacall a year after To Have And Have Not was released. As a 19-year-old, Bacall had no illusions about marriage lasting. Raised by a single mother, Bacall reasoned: to be married five years was to be married forever. Her marriage to Bogart lasted twelve years, up until his death from cancer in 1957. Bacall — after six decades working as an actress and having remarried — expressed frustration that her obituary would likely focus too much on Bogart. Yet she frequently noted her time with him was the happiest period of her life. In a 2011 Vanity Fair interview, she said it was "(b)ecause I married a man who adored me and who taught me everything about life and movies and people and exposed me to the best part of living, which was talented, creative people. And all of his absolute devotion to the truth, to honesty, to honor, and to laughter — to everything. How could I not find that the years that changed me completely and that gave me a life were the happiest? I didn't have to think of anything."

"Beginning to think is beginning to be undermined." So wrote Albert Camus at the beginning of "The Myth of Sisyphus," a 1942 essay on suicide and the absurd, which concludes with a call to see Sisyphus, forever pushing a rock up a hill, as a happy man. The mind's natural state is to be enchained, Camus said, but freedom is possible when one acknowledges that the world is without absolute meaning. Death is our only reality, and yet there remains in us a desire for unity and a longing to solve. It is that very "divorce between man and his life" which is the feeling of the absurd. The absurd is born from the confrontation between "the unreasonable silence of the world" and man's desire for happiness and reason.

Turns out Camus was also in love with Bogart. Photographs of the writer show him looking slightly worked-over, cigarette dangling from the corner of his mouth, the collar of his trench coat turned up. It's an emulation of Bogart from, perhaps, The Big Sleep, a 1946 film noir where Bogart plays Philip Marlowe from Raymond Chandler's hard-boiled novel — with Bacall as Vivian Rutledge. It's easy to understand why Camus would be drawn to noir. The stories tend to be complex and centered around morally ambiguous characters trapped in dark predicaments. And Bogart's Marlowe is Camus' absurd man. He lives his fate to the brink of annihilation, operating at times with humor and affection, motivated by an internal morality of his own biases. Camus adored the work of actors. In "The Myth of Sisyphus," he explains how in two hours an actor goes through the experiences of a life, even death. They revolt against the absurd. "Creating is living doubly," Camus wrote. The person who creates, "their whole effort is to examine, to enlarge, and to enrich" the world.

It's striking how effectively Bacall, at 19, plays the role of Slim. The older Bacall credited her younger self's vivid imagination, but it was also her skill. Bacall had one year of study, when she was 16, at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York City. There she learned to see acting as a study of life. Her potential was evident, but her family couldn't afford an additional year when it was offered, and the Academy would not give scholarships to women.

Bacall's second movie, Confidential Agent, received terrible reviews — she felt she had been miscast and abandoned by the director. Afterwards her career was an ongoing search for the right part, the right direction. A May 1950 Associated Press article ran with the headline Lauren Bacall Suspended Again. "It's getting to be a habit with Lauren Bacall. Warner Brothers studio yesterday announced her suspension, the sixth since 1944 because she refused the role assigned her... Miss Bacall, wife of Humphrey Bogart, didn't like the part and said so." She had always been tenacious, from hawking theater papers at lunch in New York in hopes of angling a break, to refusing to allow the make-up crew of To Have and Have Not to alter her hairline or eyebrows. She also resisted cosmetic surgery. "I think your whole life shows in your face," — another famous quote — "and you should be proud of that." She did allow the studio to change her name, but behind the scenes she was always Betty — or Baby, as Bogart would call her. She'd fight for a movie, too, if she wanted it. She took the role meant for Grace Kelly in 1957's Designing Woman by accepting a lower salary. She needed an escape from her home and, I suspect, refuge from the emotional experience of losing Bogart to cancer.

The absurd person, devoid of hope and conscious of it, is always tempted by escape. There's no judgment here. To recover, he admits he does not fully understand. "This heart within me I can feel... This world I can touch... There ends my knowledge, and the rest is construction" ("The Myth of Sisyphus"). He becomes an amateur creating and re-creating his present. In his rebellion, he has ceased to belong to the future. When Bacall was on the BBC program "Scene By Scene," she was asked by Mark Cousins what she would do if all her films disappeared. Bacall replied: "That's life. What could I do? ...If things last they last. And I don't do things for posterity anyway."

Being deprived of hope is not the same as despairing, wrote Camus. If the absurd cancels the hope for eternal freedom, it restores and magnifies one's freedom to act. And as absurdity springs from a comparison, to live is to be awake to see and evaluate difference. Thankfully, the human brain is a magnificent difference detector, and some of our happiness comes from our experiences of unhappiness. This is a kind of gratitude: I can be happy right now because I'm inside a warm room and not outside in the subzero temperatures. I am grateful to know what such cold feels like, otherwise I might not appreciate this.

Okay. That's a small thing.

What about the systematic imprisonment, torture, and killing of black men in this country?

In November 1940, as the Second World War was gathering momentum, Camus wrote in his diary, "Understand this: we can despair of the meaning of life, but not of particular forms it takes; we can despair of existence, for we have no power over it, but not of history, where the individual can do everything. It is individuals who are killing us today. Why should not individuals manage to give the world peace? We must simply begin without thinking of such grandiose aims."

Life's value is in revolt. "It is a constant confrontation between man and his own obscurity," wrote Camus. And the obscurity of others. The point, if there is one, is to live by active encounter, to rebel against annihilation. When a person revolts, as Camus later wrote in "The Rebel," that person identifies with others, and surpasses herself.

In 1947, Bacall, along with nearly 80 other Hollywood personalities, signed a petition protesting the actions of the House Un-American Activities Committee, which at the time was holding hearings into alleged communist propagandists in Hollywood — and resulted in the blacklisting of hundreds of artists. Bacall flew to D.C. and gave a statement before Congress: "I am an outraged and angry citizen who feels that my basic civil liberties are being taken away from me," she said.

Today, we might see a similar story on Facebook and "like" it. Am I to feel resolved? I am not comforted. "I understand... why the doctrines that explain everything to me also debilitate me at the same time," Camus wrote. "They relieve me of the weight of my own life, and yet I must carry it alone."

I don't use social media much. It's mostly a gallery for photos of my nieces. And I don't give public readings much, so I wanted to use this opportunity to say a few simple things:

Black lives matter. To me.

I like it when people want to talk about race.

I want to talk about race.

I'm anxious when people talk about race.

I'm aware of my privilege.

I'm aware of my ignorance.

I'll keep learning.

I like it when white people want to talk about race.

I'm anxious when there are only white people in a room talking about race.

But I'm not judging. We need the talk, but the more public the better.

Also, transgendered lives matter to me. The same anxieties apply.

Also, all lives matter to me.

To have or have not is about differences.

To have love or not.

To have economic security or not.

To have the freedom to walk the street without fear or not.

To have the freedom to determine the value of your life or not.

To have community or not.

To have happiness or not.

To fight the unreasonable silence of the world or not.

~*~

One can turn to scientific studies and develop happiness like a skill: be playful; seek out new experiences; develop strong connections with family and friends; serve others; practice gratitude. That sounds good.

And one can turn to chocolate, known for its mood-enhancing chemicals. In 1971, Bacall became a spokesperson for Bissinger's. "I just said 'Bissinger's is the best chocolate' into a microphone when I was in St. Louis," she told Vanity Fair, "and every year the boxes of chocolate keep coming." The Bissinger catalog description for Bear Claws reads, "Recommended by Lauren Bacall." Bissinger's chocolate factory is located in St. Louis, 12 miles from Ferguson.

In one story of revolt, the goal a shared happiness, all roads lead from Ferguson. Every day we are amateurs, creating and re-creating our world until the end.

Let's get happy. Together.

[At the end of the public reading, chocolate turtles — also known as bear claws — were passed out to the audience.]

* This quote is often attributed to Lauren Bacall. It is also attributed to Richard Bach, from his 1977 novel Illusions.

~*~

John Rich is a writer, performer, and teacher. He is also the Director of the Guild Literary Complex.