| « 'Chicago's Favorite Chicago Books' Review: Crossing California | What Are Your Live Lit Pet Peeves? » |

Author Wed Sep 11 2013

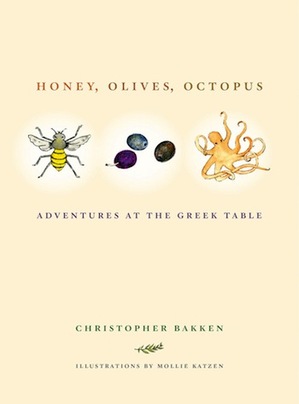

Author Christopher Bakken Discusses New Culinary Memoir

If you're like me, anything you know about Greek cuisine comes from My Big Fat Greek Wedding. Do yourself a favor, put down the remote and crack open Christopher Bakken's new book Honey, Olives, Octopus: Adventures at the Greek Table. You won't find ruminations on pedestrian hummus or cheesy saganaki in these pages. Instead, Bakken takes readers on a journey around the archipelago that gets into the nitty-gritty of Greek staples: olives, bread, fish, cheese, meat, beans, wine, and honey. The result is a mouthwatering romp around the country, which never fails to celebrate the simplicity of ingredients nor the painstaking labor that makes that simplicity possible.

If you're like me, anything you know about Greek cuisine comes from My Big Fat Greek Wedding. Do yourself a favor, put down the remote and crack open Christopher Bakken's new book Honey, Olives, Octopus: Adventures at the Greek Table. You won't find ruminations on pedestrian hummus or cheesy saganaki in these pages. Instead, Bakken takes readers on a journey around the archipelago that gets into the nitty-gritty of Greek staples: olives, bread, fish, cheese, meat, beans, wine, and honey. The result is a mouthwatering romp around the country, which never fails to celebrate the simplicity of ingredients nor the painstaking labor that makes that simplicity possible.

Bakken will present his book at the National Hellenic Museum on Thursday, September 12 at 6pm. The event is free with museum admission ($10 for adults, $8 for seniors/students, $7 for children over 3). Light refreshments will be served, and one can only hope that they're even half as good as the dishes he describes. Before his visit to Chicago, Book Club caught up with Bakken. We discussed impractical recipes, the Midwestern and Greek value system, the importance of grandmothers and, of course, his book.

How did your love affair with Greece begin?

It begins in New York City, in fact. I found a book in a garbage can in my old office on Union Square -- the book was called Teaching Overseas. I was just about to finish my MFA program at Columbia, which is to say I was very deep in debt. So I applied to teach at a number of schools near the equator and beautiful water. At the very last minute, I was hired to teach at a school in Thessaloniki and I pretty much just packed up my stuff and moved there. I had studied Greek art history and was kind of a philhellene, but I'd never set foot on European soil. I wound up living in Greece for two years teaching at a small college and coaching soccer. They gave me an envelope full of drachmas each month; I had a motorcycle; that meant I could go on the weekends to every single island within reach by the local ferry. Needless to say, there was no looking back. I was completely smitten with the place. Part of the attraction for me was the Greek table. I fell in love with the food immediately, the simplicity of it and the freshness of it. The first Greek I learned was actually in restaurants, so my entry into the Greek language came at the Greek table. I eventually moved to Houston to do my PhD, but I've been going back to Greece every single year. I'm happy to say I'm still very much in love.

Since then, you've written two poetry collections and translated a collection of Greek poetry. What prompted you to write a culinary memoir, which is a totally different genre than what you're used to?

When you're in love with a place like Greece, you need to find reasons to go back. The book of translations came about because I found a poet I wanted to work with and it meant I had a reason to spend some of my winter in Greece. But my Greek isn't really good enough to keep me busy as a full-time translator, and how many books of poetry can I really write about Greece before I need to write about something else?

Then this happened: my brother, at the age of 37 had, in the space of one month, a heart attack, a neck tumor and a divorce. Because we grew up on dairy farms in Wisconsin, we share the belief that if we want to cure whatever ails you, you go do some physical labor. I said to him, "Hey man, I got a little too drunk last summer in the island of Thasos and promised my host that I would be back for the fall olive harvest in November. Let's go." And so we went. In order to fund this trip, I proposed to Bon Appétit magazine that I would write a small piece for them on the olive harvest in Thasos and a particular olive called the throumbes of Thasos. They basically said, "You're a poet. We don't know anything about you. We don't even know if you can write a sentence." But their tepid interest was enough to send me on the trip. I ended up writing 13,000 words on olives and a whole bunch of other stuff. It was an absolute joy to write. Those 13,000 words just came out of me, in part, because for 20 years I'd been preparing to write this book. It provided me with a way to embrace Greek culture, at least as I understood it, through the lens of food. Once I finished that chapter and published it, I thought "Well, that was fun, let me do that again." Pretty soon it became clear to me that what I wanted to do was go in search of the artisans, the old ladies and old men, those people who still know how to do things the traditional way, and to find them soon, before their generation died out.

I found some of the most moving passages in the book to be about the tremendous amount of work that's behind a great olive or a squid dish. You write about your participation in these activities. Was it hard to go from the life of an academic and a writer to these very hands-on jobs?

I'm kind of an action-adventure guy. I still play ice hockey and I still play soccer with college students half my age. It's not easy for me to sit still at my desk. So at a certain level, it wasn't that much of an adjustment. On the other hand, it helped me remember what an enormous investment in time and labor it takes to live and eat in a true slow food culture. That's just agriculture at its most basic: it requires diligence and determination and a whole lot of spunk. My Wisconsin farming roots instilled in me the idea that working with your hands and working with the earth is probably the best kind of work you can do. So my Midwestern value system found something it recognized in the Greek agricultural tradition.

The recipes you incorporated in your book all sound really delicious, but what I liked most about them was that they're not adapted to suit American needs. Why write the recipes that way?

People who buy my book expecting a cookbook will be disappointed. The recipes are hardly practical. Most of us, especially those of you living in Chicago, don't have the luxury of going out, harpooning an octopus, and then doing all the things I describe to prepare a typical dish. My idea was to show what's at stake in actually making a traditional Greek dish if you're thinking of it from the field to the table, or from the sea to the table, and to really emphasize the process by which simple, fresh, seasonal food gets on to the plate. The recipes are a way to reinforce the ethos of the culinary tradition that I'm describing in the book. So I offer recipes that are as much a narrative as much as they are traditional step-by-step instructions. They also gave me occasion to delve into things that I didn't have an occasion to discuss in the longer chapters, like what a pita is in Greece, which is something other than a pocket bread, or to talk about salates, which are very different from the tossed salads we have here. My editor asked me about 14 times, "Do you really think we should keep the recipes in there?" I'd say, "Yes, I think they should stay. They're impractical, but that's the point."

You declare right at the beginning of the book that Greek cuisine is one of the most underappreciated cuisines in Europe. Why do you think that is?

First, Greek cuisine is not built from high-end restaurant culture on down. Instead, Greek cuisine starts in the kitchen of your grandmother. That's true in France and Italy as well, except the sort of celebrity culture of food that exists in other places has never developed in Greece, in part because Greece has been poorer than most of these other countries. So the beauties of the cuisine are known within Greece, but aren't so well known outside its borders.

The other thing that has kept Greek cuisine from becoming appreciated is tourism. So many people travel to Greece and eat very poorly and assume what they ate represents Greek cuisine. It is possible to have a bad meal in Italy, but it's not easy. It's pretty easy to get a bad meal in Greece, especially if you are on a big cruise and eat only at tourist restaurants. If so, you're going to eat what is essentially a clichéd version of Greek cuisine, one that is familiar: a gloppy moussaka dish, or a greasy gyro sandwich, or some overcooked lamb. But these are dishes that aren't really the centerpiece of most good Greek restaurant menus. They are certainly not the kind of dishes that I'm describing in my book. What we think of as Greek food in most "Greek" restaurants in the US is really a distant cousin from most of the food you eat at an average meal in Greece, which is typically based around fresh vegetables and beans, and typically has no more than about three really excellent ingredients. A great Greek dish typically doesn't need much more than that. A perfectly cooked vegetable or fish dressed with some great olive oil and some sea salt. You don't need much more than that. Now that local and sustainable and organic have become popular buzzwords, I think people will come to appreciate what the Greek table has to offer. Greek cuisine has always been local and sustainable and organic. It's never been anything but that. That's one of the reasons why I think it's an interesting moment to celebrate this tradition.

Greece has been in the news for all the wrong reasons lately. What do you want readers to take away from this book?

In this moment of economic tragedy and chaos in Greece, one of the things that is emerging is the bedrock of the Greek value system: simplicity, self-sufficiency, hard work. Those are the things that have always sustained Greece. It's a country that's endured lots of suffering and foreign occupation and poverty. But the dinner table is still at the center of the Greek universe, and even in this moment of disaster, the Greeks are remembering what gives them strength: sitting around the table with family members and friends, eating things that your mother has whipped up in the kitchen, or that your uncle just dragged in from the sea. That's the central joy of living in a place like Greece. No matter what the economic situation is, eating right and savoring conversation and company -- those are the things the Greeks still make time to do.

Image courtesy of the University of California Press website