Do you think of yourself as a Midwesterner? A Northerner? If you live in Chicago, author Ted McClelland would call you a Great Laker. McClelland spent last summer driving around the Great Lakes — a 9,600-mile trip that took him as far west as Duluth, Minnesota, and as far east as Kingston, Ontario — to research his upcoming book, The Third Coast, which looks at the Lakes as a distinct region of North America, with its own culture and common interests. Gapers Block is pleased to present a series of excerpts from the book over the next several months.

Mackinac Island, Michigan

Even as a boy in St. Ignace, Brother Jim Boynton idolized Jacques Marquette. When Jim was four years old, his father, the local postmaster, took him to the village's Tricentennial Pageant. There, he saw an actor wearing the "Black Robe" — the floor-length cassock of the French Jesuits who settled the Straits of Mackinac. Jim's "Jesuit obsession" was born. In grade school, he played "voyageurs and Indians" with his classmates. As a teenager, he and a friend paddled a canoe to Mackinac Island, because that was how Marquette had traveled. When he it was time for college, Jim applied to Marquette. They turned him down, because his grades were poor in every subject but history. He got into Lake Superior State instead. One Friday afternoon, he was riding his bicycle around Sault Ste. Marie. On Marquette Street, he was hailed by a man working in his garden.

The gardener was a Jesuit priest, who knew some of Jim's relatives. The two stayed up late talking, and the next Monday, Jim enlisted in the Society of Jesus. He became a monk, because during a retreat, he had a vision of Jesus as his brother, but he was no cloistered monk. Assigned to teach history at University of Detroit High School, he lived in a single room on campus, with his Bible and his volumes of Francis Parkman's "France and England in North America."

Marquette was 29 when he was called to Mackinac Island. Jim was 25. In 1992, the Jesuits, aging and dying like the rest of the Catholic clergy, withdrew their priests from the Upper Peninsula, re-assigning them to Columbus, Ohio. Jim was distraught. The Jesuits had been in the U.P. for 324 years — an unbroken line going back to Marquette. The young monk resolved to restore the Jesuit presence himself. He got permission to summer on Mackinac Island — not the hardship post it was in Marquette's day, but he made himself useful around Ste. Anne Church, compiling a museum of vestments, stoles, medals, Indian prayer books, and a bell forged in the 1830s. He scanned the parish records to CD-ROM. They went back to 1695, and included the names of his own ancestors. He wrote a short book, Fishers of Men: The Jesuit Mission at Mackinac.

More than a decade later, Jim was running Ste. Anne during the summer months. He had engineered the installation of a Jesuit pastor — the first since the 1920s — and was hosting a half-score of priests for a retreat before their final orders. When I called to see about spending a few days on Mackinac, Jim offered me a bed. He was in charge now. He could do that.

~*~

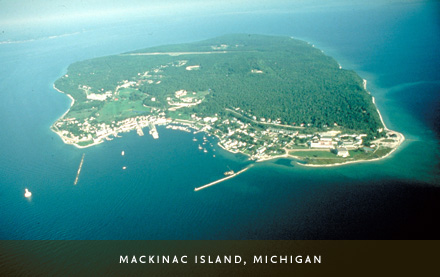

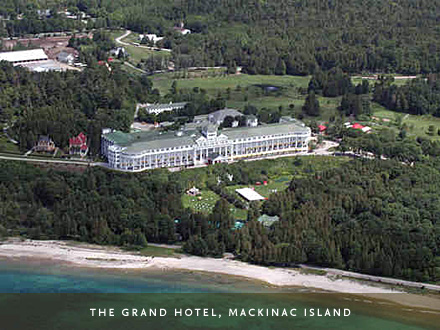

I boarded a morning ferry in St. Ignace for the 20-minute churn across the Straits of Mackinac. Sitting amongst a Francophone tour group from Quebec, I watched the island resolve into focus. Seen from the Upper Peninsula, its hazy greenery has the military hue of the spongy sprigs on a model railroad diorama. As the boat drew closer, the colors deepened, and the whitewashed cottages came out of hiding. So did the Grand Hotel, an Appolonian temple on a woodland bluff. The summer resorts were laid out in a sort of Morse code — dozens of dots, and one very long dash.

When the ferry docked downtown, the Hotel's horse-drawn luggage cart was waiting. Cars are banned on Mackinac, as are skateboards and roller blades, so the wharf side scene was something out of Melville: horses tapped out weary canters on the asphalt, while broom and shovel men, detailed by the village, swept up their cloying turds. Main Street, with its buggy traffic and its flat-profiled storefronts crowding the sidewalk, could have been the set of The Music Man. The tourist count rises with the sun, and at 10:30, we were shouldering past each other to get a look at confectioners mixing planks of fudge in the window of Ryba's.

The church was east of downtown. I toted my backpack past the old hilltop fort, which presides over the harbor along with the even more prominently placed Governor's Cottage. That gray mansion is far larger than the ranch house the governor gets in Lansing. It looks like reason enough to run for office, right there.

The most pretentious cottages are on the bluffs, but even down at water level, the turreted Victorians with their stained glass windows were bigger than anyplace I'd ever lived. In the front yard of a lavender-trimmed cottage, a woman was gardening. A tourist paused to compliment her.

"You have a nice house," the tourist said.

"Tha-a-a-nks," the gardener responded, her drawn-out Michigan vowels spiking her gratitude just enough to make it clear that she knew she had a nice house, and didn't need the approval of a day-tripping vacationer.

Somewhere on this island, monks and priests were fulfilling their vows of poverty.

When I arrived at the Ste. Anne Parish House, I found Jim sitting behind the desk, in the front parlor. It was his room: a black robe draped from a peg, and leaning against the piano was his violin case, stickered with "Yooper," "Save Tibet," and "Proud to be Chippewa."

"Was I expecting you?" he asked, when I introduced myself. He looked puzzled, but he was quizzing himself, not me. "Yyyyes! I was expecting you," he shouted, after a blank moment. And right away, he assigned me a role in his summer pageant.

"You'll be sleeping in the second room in the basement, next to mine" — his crisp Northern accent made him sound all the brisker. "Why don't we set up a time to talk?"

He produced a little black book and a pencil.

"How does 4 o'clock sound?"

My day was wide open. This was Mackinac. Where space contracts and time expands, which is why islands are the perfect resorts.

Jim scribbled in the appointment.

"That'll give you time to visit the fort. There's a real neat museum there. I'll give you my pass so you can get in for free. Just tell them you're me."

Then we were done until 4, and Brother Jim was on to his next task.

"There's a woman from the local paper coming at noon to do a story about the retreat," he informed one of his priests. "I want to get everyone together for a group photo. It'll be good for vocations."

Our appointment, which took place in the screened-in porch, overlooking the traffic on Main Street, was the only time in two days Jim sat still and talked about his work. Thirty-eight is not an age for reflection, even if you're a monk. There's a career to build. That day, he'd been recruiting volunteers to teach English to the Mexican gardeners and chambermaids at the Grand Hotel.

"The problem is they could never come down here," he said. "The only time they were free is on their lunch hour, so that's when we do it. It took years just to get permission from the Hotel."

Mackinac's 19th Century division between masters and servants meant the Jesuits still had real work on the island. They weren't just summering here for nostalgia's sake, as actors in a historic re-enactment.

"If you look at our missions, Jesuits have worked with the top of society and the bottom of society," he said. "I know a lot of the Bluff People [the vacationers in $2 million homes]. After Mass, the governor says 'Hi, Jim.' But I do most of my work with the bottom. What I hope to get next summer would be two Jesuit scholastics from Venezuela to teach English on a formal level."

(Jim knew the year-rounders as well. Once a week, he played country fiddle at the Mustang Lounge with Jason St. Onge, who sits on the town council.)

And then Jim cast me in another role in his pageant.

"The classes are at 4 o'clock tomorrow," he said. "We could use you as a teacher if you'd like to come."

"Absolutely," I said.

"OK. Meet me here at 3:20. We'll walk up."

And then he hurried across the street to the church, where he was planning a Spanish Mass for the next evening.

~*~

We walked up the long hill to the Hotel with Father Mike Vincent, a hefty, florid priest from Cleveland, who paused for breath every few hundred yards.

"This is my first time here," Father Mike told me as Jim jabbered into his cell phone and made notes in the little black book. "Jim has brought the Jesuits back to the parish. I knew that there were Jesuits missionaries in the Midwest. I knew that we had these 17th Century saints who were martyred by Indians. Until I met Jim, I did not know that there were Jesuits on Mackinac Island."

The Grand Hotel doesn't look so imposing from the harbor. It's sort of a misty white plantation house, floating between trees and sky. The closer you get, though, the more out of scale it looks compared to its little island, until you think there's no landscape that could accommodate a building this vast. A Gilded Age boast of privilege, the Grand Hotel is the grandstand at Saratoga, the clubhouse at Augusta National, the railroad magnate's cottage at Newport, blown up beyond robber baron proportions. I spent two nights there when I was 21, and I remember long hallways, cramped rooms with hard beds and pilled coverlets, windows filled to the sashes with water as pale as the sky. I also remember being scolded for not wearing a jacket and tie after six, and being served caviar by West Indian waiters whose uniforms — white gloves and waist-length blue jackets — were as archaic as the illustration on a box of Uncle Ben's rice. The Grand Hotel was the setting for the 1980 movie Somewhere In Time, in which Christopher Reeve travels back to 1900 to romance a woman he's seen on a calendar. At the Grand Hotel, how could you tell the difference between 1980 and 1900? Your room key unlocked the illusion that the 20th Century had never happened.

It costs $10 to walk on the porch — the longest porch in the world, according to Guinness — so we entered the Hotel through the service bay. Outside the gate, Jim recognized Mattie, a rotund chambermaid in a frilled apron. While they greeted each other in Spanish, my eyes zoomed upward to the porch, which seemed to be a hundred feet above my head. It was beyond human size: I felt I'd been digitally shrunk and placed in a resort scene. Only the steps of the United States Capitol have made me feel as insignificant.

The Jesuits and I walked past tanks of propane and empty luggage dollies, suffering the starchy humidity of the laundry to get to the servants' mess, a cafeteria called Captain's Cove.

My student was named Juan Carlos. He was 31 years old, from Mexico City, and he groomed the Grand Hotel's golf course. Juan Carlos had been on the island for two-and-a-half months, but he lived in complete social isolation from the guests, or anyone else who spoke English. His black baseball cap read "MACKINAC ISLAND," but he could not pronounce either word.

"I have been to Iceland one time," he told me.

"Iceland? The country way up north?"

I pointed into the air.

"No." Juan Carlos pointed at the floor. "This Iceland."

"Oh," I said. "Island. Do you know the name of the island?"

"Mackinack."

Well, that was no worse than most out-of-staters. For the rest of the hour, we worked on island words. I taught Juan Carlos how to pronounce "Michigan," "Huron," "carriage" and "cottage."

"If I were rich, I would buy a cottage," I said, using the last word in a sentence.

"Everyone in America is rich," Juan Carlos responded.

"Not as rich as this. Some of these cottages cost over a million dollars. Governor Granholm has a house on Mackinac Island."

"I was there," he said eagerly. "As wider."

"As what?"

"You know, wider. Give drink."

"Oh, waiter."

I wrote out that word as well.

Juan Carlos would be working as a waiter that evening, on the porch, in a black jacket and bow tie. But he preferred the golf course. He was studying landscaping at a college in Mexico City, and once his education was paid for, he wanted to be a groundskeeper at a school.

Five o'clock was the free hour between lunch and cocktails. The red-capped bellhops and blue-jacketed waiters filed in for their meals. As I stood on line behind a Jamaican chef, I read an article from Gourmet magazine, framed and hanging in the hallway. It named the Grand one of the Top 25 Hotels In The World.

"Can you believe that?" the chef scoffed. "It's good to see once. Then..." He shrugged. "They don't even have air conditioning. And it's full of ghosts."

"Whose ghosts?"

I was sure he was pulling my leg, but you never know when you're going to hear a good story.

"Everyone who was ever here," he laughed. "I saw one in the kitchen. I hope I wasn't drunk."

~*~

Jim commandeered a bicycle for the trip down the hill. I didn't see him again until 8 o'clock. He was unpacking his fiddle for the square dance on the deck beside the church. His father, Ollie, had come over on the ferry to do the calling. College students, freed from their shifts in gift shops and diners, sat edgily on benches until Jim plugged into an amp and broke into a reel.

"Oh, Johnny oh, now, oh Johnny oh!" sang Ollie, the retired postmaster of St. Ignace. "Sing oh Johnny, oh my, oh Johnny oh!"

I'm no dancer, so I slipped across the street to the rectory. It was empty, except for Father Rey Garcia, the pastor of Ste. Anne, playing etudes on the piano. Father Rey had met Jim many years before, at a conference in Chicago. Jim invited him to the island to work with the Latino and Filipinos. It was all part of a plot to install Father Rey at Ste. Anne.

"I think he awakened the spirit of the Jesuits here," Father Rey said. "The bishop told me, 'We want Jesuits here, because this is your area.'"

In spite of his title, Fr. Rey knew who ran the parish between June and September: "Jim has terrific energy and he knows how to use it." Then he laughed. "I dare not to interfere. I'm older."

But he wasn't too old to cross the street and join the final circle of the square dance. It was 10 o'clock by then. A bugler blew taps in the fort. Bicycles appeared from the darkness, pedaled by dishwashers who'd just finished work at the Hotel. Father Rey, now in white-and-gold vestments, delivered the homily, and the Mexicans sang along to Jim's soft guitars and prayed before the flickering Virgin candles in tall glass tubes. The Jesuits had celebrated mass here in Huron, Ojibway, French and English. They learned the language of any tribe that found its way to Mackinac.

After the service, there were tamales and flan in the basement, and second-hand clothing piled on tables. A few of the workers paged through coats.

"How late will the last person be here?" someone asked Jim.

"That'll be me," he said. "In half an hour, this place'll be empty."

He gestured to a maid. They'd been sharing dessert.

"She's has to be up at 5:30 to work at six in the morning," he said. "And I've got to get up tomorrow and plan a dinner for 200 people this Friday."

Read on:

1. Sheboygan & Manitowoc County, Wisconsin

2. Marquette, Michigan

3. Mackinac Island, Michigan

4. Grand Marais, Minnesota

5. Pays Plat First Nations Reserve, Ontario, Canada

6. Isle Royale, Michigan

7. Rogers City, Michigan

8. Toronto, Canada

9. Hamilton, Ontario

10. Hamburg, New York

Buy the book.