| « Really Quick Contest: All that Jazz! | Really Quick Contest! Music History VIP » |

Feature Thu Dec 21 2006

From Uptown to Downtown, Our Roots Run Deep with Music

Last month, the Chicago History Museum, which celebrated its 150th anniversary earlier this year with a name change and a significant renovation, unveiled "Chicago Roots Music," an exploration of the city's unique and vibrant musical roots. While what makes up "roots music" could be open to a number of discussions, Alison Eisendrath, the exhibit's curator and the museum's Senior Collection Manger, defines Chicago's roots scene as music brought to the city by migrants from other parts of the States.

For the most part, it was rural southerners who migrated to Chicago in the early 20th century for economic and cultural opportunity. Black southerners from Louisiana, Arkansas and Mississippi took the Illinois Central Railroad into Chicago, one of the country's biggest railroad hubs, bringing along with them New Orleans' young jazz culture. In 1922, Louis Armstrong left Louisiana and arrived in Chicago to elevate jazz into a soloist's art. From the Appalachian states, white southerners were also migrating to Chicago, and soon "Live Hillbilly Music" was being advertised in Uptown taverns. The story of Chicago roots music a big story to tell, so rather than "tell[ing] the full history in watered-down form, we focused on individuals to tell the big story," Eisendrath said.

Louis Armstrong outside the Blue Note nightclub,

ca. 1955. (Photograph by Bill Mark), Gift of Frank Holzfeind,

Chicago History Museum

The stories "Chicago Roots Music" tells are varied, but of common spirit. There's the story of Thomas Dorsey, a music director at a South Side church who became the "Father of Gospel Music" and the first African-American inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame. The piano where Dorsey composed some of gospel's most famous standards is currently on display at the museum, alongside Mahalia Jackson's choir robe. Both Dorsey and Jackson, the latter whom some consider as "The World's Greatest Gospel Singer," also popularized the genre, as it left the church and found an audience in both black and white listeners.

There's also the story of Red Foley, a white Kentuckian who recorded the first gospel record to sell more than a million copies, and became a star on the WLS National Barn Dance during the 1930s. As a precursor to Nashville's Grand Ole Opry, the hugely popular radio show, broadcasted from Sears' mega-watt radio station (WLS stands for "World's Largest Store"), introduced listeners to Appalachian mountain ballads and singing cowboys like Gene Autry and Rex Allen.

Jon Langford, a Welshman who moved to Chicago in the '80s as a member of the seminal punk band The Mekons and later played an important role of the city's own "insurgent country" movement with his latter band The Waco Brothers, is also a featured player in the exhibit. His Pine Valley Cosmonauts paid homage to the WLS Barn Dance by recreating a Saturday night on the album "Barn Dance Favorites," while some of Langford's artwork — faded, folky portraits of Country-western heroes — are on display. Langford can also be seen in the WTTW-produced documentary,"American Roots Music: Chicago." A portion of the film can be seen at museum and also features Studs Terkel and Jeff Tweedy weighing in on the city's roots music.

Rounding out the visit to "Chicago Roots Music" are stops by The Old Town School of Folk Music, which will celebrate its 50th anniversary next year, and old Maxwell Street, where electric blues was born. It's also the subject of an upcoming documentary called "Cheat You Fair: The Story of Maxwell Street."

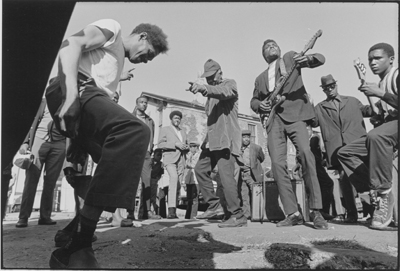

Music and dancing with Li'l Pat, Peoria Street

between Maxwell and 14th Streets, 1971.

Gift of photographer James Newberry, Chicago History Museum

These days, many of the sites that literally housed the music are long gone. Scene clubhouses like the R.R. Ranch, where The Sundowners spent a 30-year residency, and The Blue Note, which hosted greats like Count Basie, succumbed to the decline of The Loop. In 1994, a controversial University of Illinois-Chicago expansion forced Maxwell Street to a new location on Canal Street (it will move again next year to Des Plaines Street). And about a year ago, a fire claimed the Pilgrim Baptist Church, the birthplace of Dorsey's gospel.

But even as the city changes, Eisendrath said the music still thrives in clubs and churches all over Chicago. From Tuesday nights at the Hideout to Sunday morning sermons on the South Side, the city stays true to its roots — It's something, Eisendrath said, that "couldn't have happened anywhere else."

-JP Pfafflin

"Chicago Roots Music" runs through May 20, 2007 at the Chicago History Museum, 1601 N. Clark Street. Suggested general admission is $12 for adults / $10 for children, students and seniors. On Mondays, admission is free. For more information, visit www.chicagohistory.org .