| « Prairie Spies @ the Empty Bottle | Hurry, Call Poison Control! » |

Feature Thu May 15 2008

Ethnomusicologists from the Armchair

Commercial music compilations have jumped the shark about eight times over at this point. Who on earth is clamoring for the 20th Century Masters: The Millennium Collection: The Best of Max Webster? When is someone looking for a classic TV theme song going to pick up this in lieu of googling it? And even when the label is doing something noble with the re-issue (like Hip-O's reissue of every single Motown 45), filesharer's guilt is even smaller when the potential buyer thinks the rewards are just going to the archivists instead of the artists.

Chicago South-siders, The Numero Group, has a novel answer to this — make the archivists (only one of many titles applicable to this versatile crew) worthy of your dime. By finding artists, labels, and sub-genres that have been otherwise forgotten by time and telling the whole story in their meaty booklets, Numero manages to dig up a very rare find indeed — a steady customer base. The label's latest collection, Soul Messages From Dimona, dropped on May 6th, and Gapers Block: Transmission sat down with Ken Shipley and Rob Sevier to figure out how many Seversons it takes to find just the right song.

Soul Messages from Dimona

Gapers Block: So what are the current stats on Numero?

Ken Shipley: We’re committed to doing about six releases a year. We finished Soul Messages about a month ago. This Tragar project we have coming out has taken so long (we did the licensing around last September) that we had to fudge our numbering system a little. It’s really tough to make these records — it’s not like recording a band and getting one of their friends to put some shitty artwork together — Twinight took us almost two years to finish.

GB: It almost sounds like a movie in of itself sometimes — scouring record shops in foreign countries for the one pristine copy of a record.

KS: It’s some of that — but we’ve really only done three records outside the U.S. And for Israel, we had a sister community of Chicagoans there that allowed us to work from here on it. And when Rob came back from Belize, he had zero records — maybe a couple cassette tapes, but we found out that most of the masters were in New York all along.

Rob Sevier: One of the biggest obstacles for us is often format — there was a situation where we had to have an 8-track 1-inch tape machine and a DBX noise reduction converter. And no place in the world has all three of those things — DBX is an esoteric noise-reduction that was a competitor of Dolby, but Dolby won.

KS: Think like Betamax. The guy we were recording with was barely familiar with it, and we had to import a ProTools system in just to get it done. We get all these old cassettes and it’s a thin line - sometimes we put a lot of effort into converting these and they’re just total crap.

Becky Severson

GB: I’d heard some wild stories about hunting down artists — that you had called every Becky Severson in Minnesota just to find one track, for example.

RS: Actually I think I called all the Seversons, period. There was no Becky, but the 23 out of 24 Seversons in St. Cloud happened to be the father of Becky. Darnell Glover was another ridiculous one — we sent letters to him for years and years, and I’d wait and do news searches. One year he finally wrote back and I went to his place in the projects on the lower South Side. I go in and it’s a tiny, narrow duplex. The walls are completely bare… except for one thing: my first letter to him, in a frame. But he’d never responded to it! And I’d written many other letters to him since then, and he hadn’t responded to any of them for years. But that’s the advantage of writing a letter — at least it sticks around.

KS: People don’t understand that maybe twenty percent of this work is fun. Most of what we do is make a list of names and call people to narrow it down, or pack boxes of records in the back here. Sometimes I think people have this idea that we’re this kind of international team of that goes around with guns — there was an interview with the guy from select frequencies where he said one of the things he carries around with him is a gun. It sounds clever, but in reality… that’s not what we do. We’re ethnomusicologists from the armchair. It’s not that we don’t do any work in the field, — it’s just not even that easy to do work in the field.

RS: But there’s some things you have to do in the field.

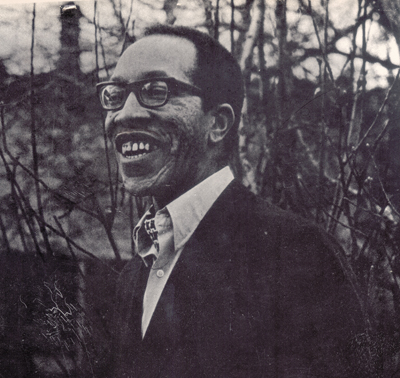

Marion Black

GB: Certain items you have to physically hunt down?

RS: The best example of that is the Marion Black story. We went and visited him to see if he had any old pictures of himself, something to represent him from 1970-72. So we get there, and the only photo he has is of him in an armchair, drinking a beer, from the late '80s. And he was old when he made the recordings to begin with, so this picture just makes him look like someone’s grandpa. But he’s cool, and we talk with him and his wife for a while, taking notes. And eventually I have to use the bathroom, so I walk upstairs…and right on the wall on the staircase is his old promo glossy from when he was performing! So I brought it down, and said: "This is what we were looking for." And his wife said that they completely forgot about that — they just walked past it everyday and never even thought about it. Or other times we go to old addresses and people have left a filing cabinet that the new owner never opened…That’s why you have to at least show up. Those are the kind of things you can’t get anywhere else.

GB: How do you guys go about organizing a record where there’s not a label’s set output? Do you have a set list of songs you must have, or do you just add as you go?

KS: Well, for example the Kid Soul record was a pet project of mine, Gospel Funk was Rob’s… you just say I think I have enough tracks, let’s go out and see what we can do. With some of these micro-genres, there’s not a lot of records to choose from — more than you think, of course, but probably only 100, 200 tracks total. Even still, we’ve got enough to do a second version — of each of those, actually. There’s about 30 tracks that we wanted, and we tried to grab as many as we could. After the release, we can still have other tracks come in, and maybe do another after the fact — but for the most part we’ve exhausted the source material, and then they’re like the labels releases — you tell as much of the story as possible, and you close the book. there’s not going to be another Deep City, another Soul Messages, another Tragar. We just can’t.

GB: But some of these remnants are getting put up on the web store now — they’re still finding their way out to the public in one way or another.

KS: We’ve started this digital dig project, and it’s still a budding concept, it was originally supposed to be like from the cutting room floor, but now we’ve got all of the tracks available — someone can just go to the site and make their own "Best of Numero" — "Best of Eccentric Soul". We can’t be opposed to downloading, because it helps the music get out there — but if you download the music, you’re kinda missing out on a lot of what we do — to me the music is only half the story. We spent a lot of time on the booklets — there’s a reason we don’t just put a birthday card in there with the track listing inside. We want to go further in and tell a story — frame this, present it — and you really can’t do that digitally. You can make great mix tapes, but that’s about it.

GB: It seems really hard these days to establish yourself as a tastemaker — you really have to have a little extra oomph" or vision to make it. There are so many outlets to find any number of niche records and genres, you need to set yourself apart somehow.

KS: It’s like a gallery — anyone can put a gallery in their house, put whatever they want on the walls, whether its line drawings or finger painting by a three-year-old, or electric bulbs, or whatever — but it’s the vision of the people running that gallery, of this label to be something that is quality. We look at this as if we’re the Folkways of the 21st Century — we’re picking up where they left off. This is the Harry Smith gathering recordings. It’s bigger than a blog. And there’s nothing wrong with that, as a hobby. But at a certain point its more interesting to have a one-of-a-kind acetate or someone’s master tapes, than some album there’s hundreds of copies of. Syl Johnson came and sang a record to me the other day — how many people can claim to that? He came and sang over an instrumental that had been released, but the vocal had never been released. He made something that publicly never existed before. And even though our core listeners are a mostly younger crowd, we’re drawing from history that is dying — these people are literally dying. We have to do this now — you may be around in sixty years, but these artists won’t, and you’ve gotta get this stuff down while you can.

GB: So if Numero were to continue for ten, twenty years down the line, how would you progress into the modern historical era? Your format right now focuses on a period where everything was just barely still there — how will you progress as history becomes better archived?

RS: Nothing is better archived — no matter what year. I’ve talked to people who were doing stuff in the '80s, and they’re still lacking all of their masters. So that part doesn’t change.

KS: We’re constantly getting into weird experiments — if you were to ask me if we would do a solo guitar record, I’d have said probably not — but here we have one, and it’s almost like the kind of music my mom would listen to. They’re pet records — we hear something we like, and it gets infectious — we have to spread it.

KS: I’m not really that worried about the future — I think there’s going to be so much more like bedroom music from the '90s — tons of people making 4-track recordings — that’s going to be something. A four-track in the 1960s was a heavy buy — in the '90s it was a couple hundred bucks. How many people worked a week at McDonald’s and bought one — it’s a different situation. We could find the next Michael Yonkers, people who are doing Lou Barlow-Sebadoh stuff … maybe the Beck of bedroom recordings. And people are going to flip out.

About the Author:

Dan Morgridge is waiting for a group to begin cataloging forgotten food, so that he can buy the first copy of Eccentric Meats: The Lost Vienna Beef Products.