| « North Coast Festival Box Office Info and Saturday Picks | Contest: Crowded House @ House of Blues! » |

Feature Thu Sep 02 2010

Michael Zerang: Harvesting Energies

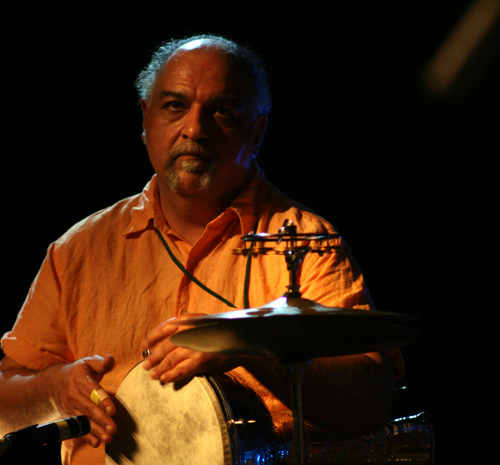

Michael Zerang (photo by Gareth Mooney)

The first thing Michael Zerang wants to talk about, following our initial chit-chat and coffee orders, is his new xylophone. "It's the thing that's most obsessing me right now," he says. Zerang rattles off numerous details about the instrument: made in the '30s, blonde with rosewood bars, four octaves — few xylophones made these days are that large. "It's an unforgiving instrument. It doesn't have a 'give' the way a vibraphone or a marimba does. It's like a bagpipe — it's either on or it's off," he laughs. He's practicing it for a performance he'll give today (September 2) at noon, as part of the Michael Zerang Organic Unit, a sextet accompanying a Butoh dance troupe at the Jay Pritzker Pavilion as part of the Chicago Jazz Festival.

Of course, xylophone is not the only tool in Zerang's arsenal. Neither, for that matter, is music his only outlet for his love of rhythm.

Casual followers of Zerang's music know him as a master jazz/free improvisational percussionist, a rock-solid base from which all manner of musical forms can spring. Whether thundering behind the well-oiled jazz compactor that is the Peter Brotzmann Tentet or grounding the transmissions of gentler musical aliens like his trio with Mats Gustafsson and Jaap Blonk, Zerang is an ensemble's lightning rod. Unlike many free improvisers, Zerang possesses a rare gift — fearlessness in the face of silence. He's just as comfortable with negative space as with filling the frame.

A first-generation American of Assyrian descent, Zerang was raised into a musical family. His mother was a pianist, and his father an amateur percussionist and music devotee, introducing his kids not just to Assyrian music, but all manner of Middle Eastern styles, including Armenian, Turkish, and Kurdish music, along with Louis Armstrong and other American jazz. There were always records playing, and the family played together too; Zerang sporadically plays in a trio called Kismet with his father, percussionist Eddie, and his brother, keyboardist Paul.

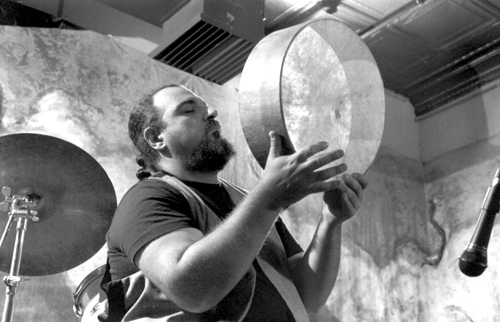

Michael Zerang (photo by Mark Pokemper)

Although he started listening to free jazz and free improv records at a young age, tapping quickly into music of Chicago's AACM and the Sun Ra Arkestra, Zerang remembers the precise moment when he made music his life. Upon hitchhiking to San Francisco in June of 1976, Zerang saw one of the final performances by the great multi-instrumentalist and musical iconoclast Rahsaan Roland Kirk. Best known for his ability to play three horns at the same time, Kirk was in his waning days by this time, suffering a series of strokes that paralyzed him on his left side.

Zerang doesn't remember the specifics of the concert, but he felt something else at work. "What was amazing about it," he remembers, "is they brought him out, propped him on a stool — he had all these horns and stuff hanging off of his chest, and his saxophones were modified so he could play them with one hand. He sat very still. Also, you have to understand, he was quite a sight to behold — he was a really big guy, big black glasses, colorful clothes. As he played, he embodied this sort of...I don't really know how to describe it even though I've talked about it before, but he was a node in time and space; energy just flowed through him, and he filtered the energy, purifying it in a way that was really overwhelming to me. I found it to be very healing and very profound. When I left, I thought, 'THAT'S what I want to do.'"

Easier said than done, of course. When Zerang returned to Chicago, he tried to translate what he had seen and heard into his own music. "I wanted to pursue that, but I had no concrete way to go about it," admits Zerang. "So, the first thing I picked up was a hand drum, a darbuka that I had laying around my house. I tried everything I could think of with it. From there, I started playing with a violinist named Daniel Scanlan. It was a very naive approach at first. We couldn't figure out how to get to the thing that Roland Kirk was doing at that time...it was something I had seen, but I just didn't know how to get there on my own."

Realizing that proficiency requires collaboration on a massive scale, Zerang created and conducted a variety of musical projects in the late '70s and early '80s. One of the earliest was called the Neutrino Orchestra. "It was a group that got together to do improvisation, and to bring different instruments from different approaches. It was kind of my young, naive improvisation group. It was great...we were all new at it, and I wouldn't necessarily release all the tapes now [laughs], but it was great learning." Following a performance art collective known as Musica Menta (1981-1986), Zerang launched Project Clamdance (1981-87) next. "It consisted of about 30 musicians, a large-scale improvisers orchestra. At the time, I was playing with some contemporary classical people, some jazz people, a few rock and roll people, and this was a chance to bring all of these people together, to see what could be learned collectively from these different approaches. This was in the early '80s in Chicago, which was an important time. It brought together a lot of different musicians and people from a lot of different walks of life."

Michael Zerang collaboration with Jim Baker, from the Memorial Concert for Malachi Ritscher, November 4, 2007. (Photo by Seth Tisue)

At this point, I wonder aloud whether he thinks that the '90s and '00s were a boon to the jazz and improv scenes in Chicago, being that they brought a huge new influx of fans and venues for experimental and improvised music to shows. Zerang agrees, but is quick to qualify. "In the '80s, you could have a scene where you could go down to Randolph Street on a Saturday night, and you'd have an art opening at 9:00, then at 10:00 there'd be performance artists, and then at midnight the bands would start. There'd be five, six hundred people there! So at that point, the scenes were all mixed, but by the '90s, things got a bit more codified, now you have the jazz over here, experimental music over here, film groups over here, and the art galleries on the other side of town, the dancers over here, and the performance artists over there. So now, each one has their own scene, and you can say, 'well look, they're all growing,' but on the other hand, it was so much more vital to be in a scene where all the different creative pursuits were working together."

Michael Zerang Solstice Concert with Hamid Drake

It was near the end of the '80s when Zerang met the collaborator with whom he is most closely linked, percussionist Hamid Drake. In 1990, the two started a yearly event that's now entering its second decade, the Winter Solstice Percussion Concert at Links Hall. Playing at sunrise and sunset over three days at the end of December, Zerang and Drake engage in 90 minutes at a time of joyous dialogue, wandering the hall between their percussion stations, carrying hand drums or bells to tide them between each oasis. "At this point, it's not a matter of establishing a dialogue — we've been playing together for over 20 years, so it's just one long dialogue," says Zerang. "The question is where do we start. If you're meeting up with an old friend, it's not a matter of whether you'll have anything to say to one another, but a question of what to start with first."

In his total devotion to the creative energies he first heard in Roland Kirk, Zerang has utilized his percussion exploration in the service of other rhythmically-rooted arts, dance and theater. In collaboration with Redmoon Theater co-founder Blair Thomas, Zerang created the musical compositions for Redmoon's large-scale puppet theater pieces, including adaptations of "Moby-Dick," "The Hunchback of Notre Dame," "The Ballad of Frankie & Johnny," and "Frankenstein."

At the same time, Zerang and his various ensembles have accompanied dance troupes for years. Today's performance at the Pritzker Pavilion, for example, features the Blushing Poppy Dance Club, a local troupe dedicated to the Japanese dance/theater style known as Butoh.

Not content to showcase his own investigation of rhythm and movement, Zerang has also been a long-time champion of others' endeavors, curating experimental performance programs in clubs and spaces all over the city. He was the founder and director of the Links Hall Performance Series (1985-1988), freelance curator of experimental music for Urbis Orbis (1995-98), and host of the Albany Park venue Candlestick Maker (2001-05). The program at Links Hall, in particular, shows Zerang's commitment to the multi-disciplinary collaborations of the arts, with a roster that varied between solo percussion by Andrew Cyrille, music by Algebra Suicide, and readings by Amy and David Sedaris. Best of all? Several years of shows are archived and available to the public!

"When I was artistic director for Links Hall from '85 to '88, that was primarily music and poetry and fiction readings then. That's all archived in the Creative Audio Archives at the Experimental Sound Studio." You can see the listings here and find out more about how to access them here.

Zerang is, by his own admission, a compulsive archivist. "There's never huge audiences for this kind of stuff while you're doing it, but I've had all these great concerts that were attended by only 15, 25 people. Why should that disappear into the ether? Now, anybody that wants to check the list can go to Experimental Sound Studio and listen to the recordings at their own pace." (The Urbis Orbis list can be seen here.

This all ties it back to that night in '76. "When I was 16, I walked into a theater and got my DNA re-arranged. So I'm still aware that, in any kind of performance or theater or musical event I help create, that a chance for that same thing to happen to someone else should always be a possibility. I feel like it's my responsibility, and the responsibility of my collaborators, to create a situation in which there is a potential for that." He lives by the 19th century notion of total mastery, committing fully and daily to his life's work, intent on capturing that spark, whether it's through free improvisation, the perfect melding of rhythm and dance, puppetry, or film. He creates and controls the musical environment, provides a clean, well-lighted place for music, and tirelessly records the past for the scholars and young impressionables of the future.

Although he tours extensively ("It's an old story, but musicians can seldom make a living in their own town," he sighs), Zerang loves Chicago as his base of operations. It's not an unconditional love, though:

"The great thing about Chicago is that there are lots of different kinds of artists willing to mix and match in unexpected combinations. New York is more of a showcase, but Chicago is a collaboration. Also, there's always an audience here — sometimes large, sometimes small, but you're never working in total isolation or total indifference. Chicago isn't just a great music city...it's a great innovative music city." Zerang wonders, however, whether the town leaders even know what they have, or what to do about it. "The thing that drives me crazy is that the city does little to nothing to acknowledge that. Sure, they're good at getting people to come to big festivals, but there's no real sense of trying to attract artists to live and work here as a viable collaborative artistic community. I just don't see it changing. I don't see it in all their laws and regulations of clubs and bars. I mean, it's really down to this: does Chicago want to be a world-class city, or does it want to be a provincial town? Why do mommy and daddy get to tell you that you have to go home at 2 a.m.?"

Michael Zerang (photo by Angeline Evans)

Michael Zerang's upcoming performances, including the Chicago Jazz Festival today at noon and quartet performance tonight at the Velvet Lounge, are listed at his website.

This feature is supported in part by a Community News Matters grant from The Chicago Community Trust and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. More information.